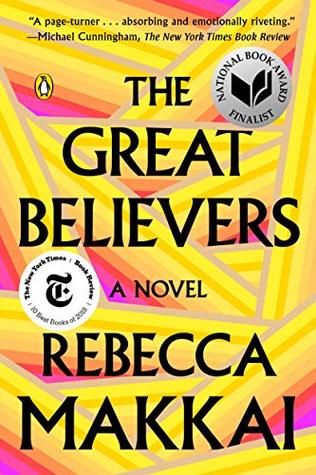

This book was heartbreaking and beautiful, just as you might assume a finalist for the National Book Award would be. It was an incredibly well written story about love and friendship, told across decades. One story line takes place starting in 1985, when a group of men – friends and lovers in Boystown in Chicago – are creating their own memorial service for their friend, Nico – the first death from AIDS that has hit this small community (but not, unfortunately, the last). The other story line takes place in 2015, mostly from the perspective of Nico’s younger sister Fiona. Fiona was very present during the events of the 1980s, loving her brother and his boyfriend and their friends as her own family. Though she’s present in the 1985 storyline, it’s primarily told from the perspective of Yale. Yale works at Northwestern as a developer for a fictional art gallery, where he is trying to acquire a collection of previously unpublished works by various artists from Paris in the 1910s. The current owner of the collection is Fiona’s great aunt Nora, who was something of a party girl back in France at that time, rubbing elbows with Modigliani and posing naked for Foujita.

The resulting story is a beautiful blend from each character’s life. Everyone feels alive and real, each character achingly present while they have the fortune to be alive. I want to say more about the story, but honestly it’s twists and turns are a joy that you should read on your own. It was fascinating to read this in our own post-pandemic world, imagining the stories of both the flu of the late 1910s and, even more present and the focus of the novel, the horror of enduring the AIDS pandemic. Makkai makes the situation palpably real, both beautiful and tragic.

I was born in the early 1980s, so I was a bit young to know much about AIDS when I was younger, but even as a young adult in the early 2000’s I think there was a great deal of panic about AIDS, especially in certain communities. The tone had changed by then to a certain degree – but, I mean, it was still a time with a great deal of homophobia, even if funding for AIDS research was in a much better place. In college, I worked as a research assistant on a study that was related to AIDS (I’m hopeless with the details today, I believe it was about metabolism of certain medications and the risk of being diagnosed with diabetes while on this medicine). I can remember that my job was to pick up the volunteers for the study and walk them through the enormous medical campus while they spent the morning getting blood draws, taking stress tests, providing samples of all kinds. I’d remain with the participants (all males, all positive), and sometimes they’d tell me stories about their life. I didn’t quite understand then, and really still only have a bare bones understanding now, of what it must have been like, to be young and facing so much unknown terror. Even in this book, the discussions between friends about whether or not to be cautious, to get tested, to attend the party or go to the bathhouse (if we don’t go, the virus wins; if we don’t go, everything fun will close; if we go, if we get sick, will it have been worth it?) -these are questions that are familiar to much of the rest of the world, post Covid-19. But there was a huge difference in how the gay community of the 1980s was made to suffer in silence, and worse, to blame themselves, to bring morality into their terror. Makkai’s book does what I love best about literature – it is a window into a community that I have not known for myself but that has so much to say about humanity.

Grab this book, and don’t forget the tissues.