The Werewolf Principle – 3/5

Not actually about werewolves, or even one werewolf. We begin this novel with a senator and his daughter coming across a man who has apparently recently returned from a trip to space, for which he was gone for 200 years of Earth time. He has no memory beyond a few basics, nothing really to say, or anything to really explain his situation. Once we get going a little bit, we come to learn that it’s possible that there’s more than one consciousness inhabiting his body, and maybe even something more strange than this going. Werewolf becomes a metaphor for this kind of split inhabitation of a body and consciousness, but also how the media describes him. More happens, as you can imagine, but the book takes us there mostly through philosophical discussions.

Although this is more “heady” than early Heinlein, the vision of the future feels very similar. It’s weird to imagine the future in 200 years walking and talking like the late 1950s but here we are. The book itself feels relatively stilted, especially given the direction that science fiction was headed in the late 1960s when this came out. But it’s also hard to write a convincing representation of having more than one consciousness as consciousness itself seemed impossible to narrate until the 20th century, and still remains nearly unrepresentable in any meaningful way in any event. So the book doesn’t ever end up being particularly good, but it’s interesting in its attempts to capture the impossible.

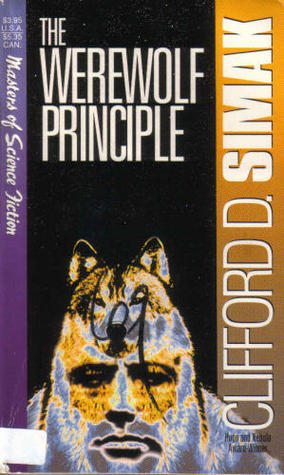

It does have this hilariously weird cover though:

The Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge – 5/5

This is my second reading of this book and maybe my second this year? I forget exactly when I first read it, but it wasn’t that long ago. I’ve thought a lot about the kinds of novels that poets write, and this is very much right in the center of what I think “the kind of novels poets write” means. In this book we have a young man wandering around Europe as he’s trying to gather together enough life experiences to become a poet. He reckons that when most people think about what is poetry, they think about the emotions that poetry that contains, but he decides that it’s more about the relation of experience, through which complex emotions can emerge. I don’t disagree and I don’t think Rilke is unaware of this, given that among his other writings, he’s the creator of “Letters to a Young Poet” which also certainly addresses this topic. This reread was not as careful as my first reading, so I have less specific things to say, but the meandering quality of someone trying to fabricate enough life experience to write about it, but in terms of creating art, does have a funny irony to it. The idea that poetry can be extruded through a kind of shape rather than something that comes to some degree naturally. Who knows. I think thinking through my two main competing definitions for poetry, William Wordsworth’s, which both emphasize emotion, but also distance and reflection, and Robert Frost’s, which emphasizes need and desire, the effect, shows that the interplay is often at the heart of everything.

The Miracles of St Cuthbert – Bede

I have never read Bede, and I think absent becoming a religious scholar in the history of Christianity in England, I am probably good, at least as far as his hagiographies is concerned. He also wrote the early, definitive, and possibly true account about the mixing of races and cultures in middle-ages Britain, so perhaps that’s something I read later on.

So what happens in a Bede hagiography? Well, a lot of small moments in the life of a saint are described. None of them is a surprise, because the lengthy titles of each section details its content. For his part, Cuthbert was a pretty busy guy. Every other page he’s saving something or almost dying or making a miracle happen. So good for him. There is no criticism here, because that’s just not the point of these.

Here’s an example:

“

CHAPTER XVII

OF THE HABITATION WHICH HE MADE FOR HIMSELF IN THE ISLAND OF FARNE, WHEN HE HAD EXPELLED THE DEVILS

WHEN he had remained some years in the monastery, he was rejoiced to be able at length, with the blessing of the abbot and brethren accompanying him, to retire to the secrecy of solitude which he had so long coveted. He rejoiced that from the long conversation with the world he was now thought worthy to be promoted to retirement and Divine contemplation: he rejoiced that he now could reach to the condition of those of whom it is sung by the Psalmist: ” The holy shall walk from virtue to virtue; the God of Gods shall be seen in Zion. ” At his first entrance upon the solitary life, he sought out the most retired spot in the outskirts of the monastery. But when he had for some time contended with the invisible adversary with prayer and fasting in this solitude, he then, aiming at higher things, sought out a more distant field for conflict, and more remote from the eyes of men. There is a certain island called Farne, in the middle of the sea, not made an island, like Lindisfarne, by the flow of the tide, which the Greeks call rheuma, and then restored to the mainland at its ebb, but lying off several miles to the East, and, consequently, surrounded on all sides by the deep and boundless ocean. No one, before God’s servant Cuthbert, had ever dared to inhabit this island alone, on account of the evil spirits which reside there: but when this servant of Christ came, armed with the helmet of salvation, the shield of faith, and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God, all the fiery darts of the wicked were extinguished, and that wicked enemy, with all his followers, were put to flight.

Christ’s soldier, therefore, having thus, by the expulsion of the tyrants, become the lawful monarch of the land, built a city fit for his empire, and houses therein suitable to his city. The building is almost of a round form, from wall to wall about four or five poles in extent: the wall on the outside is higher than a man, but within, by excavating the rock, he made it much deeper, to prevent the eyes and the thoughts from wandering, that the mind might be wholly bent on heavenly things, and the pious inhabitant might behold nothing from his residence but the heavens above him. The wall was constructed, not of hewn stones or of brick and mortar, but of rough stones and turf, which had been taken out from the ground within. Some of them were so large that four men could hardly have lifted them, but Cuthbert himself, with angels helping him, had raised them up and placed them on the wall. There were two chambers in the house, one an oratory, the other for domestic purposes. He finished the walls of them by digging round and cutting away the natural soil within and without, and formed the roof out of rough poles and straw. Moreover, at the landing-place of the island he built a large house, in which the brethren who visited him might be received and rest themselves, and not far from it there was a fountain of water or their use.”

I Served the King of England – 3/5

This is one of those “instrumental to understanding the culture and language of a people” kind of books that is usually completely lost on me. Apparently the Czech is quite difficult to understand and the translation seems good and fetching, but I found myself glazing over when I read this.

It DOES have one of the best titles for a novel though.