This book broke me (and my reading slump). And then the author’s note broke me again.

This book broke me (and my reading slump). And then the author’s note broke me again.

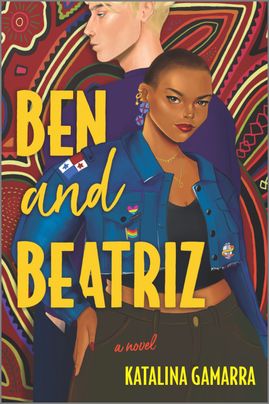

Plot: Ben is your typical rich cishet white dude from a family so rich they’ve been able to ignore the last century in civil rights advancements. Beatriz is a queer, Latinx woman with zero chill about systemic discrimination and generational wealth in the negatives. His family voted for Orange Hitler, obviously, while his win has paralyzed Beatriz with fear and anger and more fear. They hate each other, but their best friends are dating, so they have to spend spring break together in his obnoxious family mansion. Shenanigans ensue.

There are so many incredibly difficult things that Gamarra manages to do fantastically well with this book.

First is that this is obviously meant to be an adaptation of Much Ado About Nothing. Even when they’re good, adaptations are good because the source material is good, not because they are good in their own right. Like the Doctor and Donna adaptation of Much Ado set in the 80s was a great take on this play, but that’s all it was. This is so damn good in its own right. It’s been years since I’ve read any Shakespeare and I remember very little of Much Ado anymore but despite not having the love of the source material to bolster it, I couldn’t sleep for reading it.

Second is the enemies to lovers trope that both the original and this book centre around. Ben and Beatriz are at odds from minute one and for obvious reasons. They are in every way natural enemies. Generally, this trope suffers on one of two fronts – either the characters don’t make sense as enemies or they don’t make sense as lovers. Writers tend to lean too hard on either the reasons for their inciting conflict and failing to resolve that conflict satisfactorily or else the conflict is a nothing to begin with. Gamarra doesn’t take those kinds of shortcuts though. These two were literally raised to see the other person as a two dimensional enemy rather than a person, and part of that upbringing means flattening out the other person’s experiences and making people feel like they know enough. Add in a hook up gone wrong, and you have a perfect recipe for two people who hate each other because of the ways society has shaped their perceptions rather than because of who they actually are. So when forced into close proximity, into acknowledging the humanity of one another, the barriers that formed their initial opinion of one another start to break down in a way that is organic and believable and satisfying.

Gamarra also managed to capture the just utter desolation and hopelessness of the Orange Hitler years in a way that instead of being depressing felt really validating, at least to me. Gamarra doesn’t solve the divide between left and right with this book. I don’t think any book can accomplish that, much to my chagrin. But reading it made me feel like we didn’t need to have the answers to do better. Sure, the asshole is out of office, but his fans are still running rampant and there are plenty of slightly more electable versions of the hate he made mainstream that are infiltrating elected office all over the place. The danger to civil liberties remains alive and well, even for folks outside the US who didn’t just have their right to bodily autonomy stripped away by the Supreme Court. And I don’t know how we fix this, or if we can fix this. But Ben and Beatriz suggests that maybe that’s the wrong question. Maybe what we should be asking is how we can be more compassionate in our every day lives. How can we own up to our mistakes and do better. And how can we be kinder to ourselves and the people around us so that we can survive this marathon that has the fate of every species on this hunk of rock is relying on.

I also want to touch on the characters themselves. There are, ostensibly, Good Guys and Bad Guys here. But there is no one that has been untouched by trauma. Everyone’s actions, even the most abhorrent stuff that happens, makes sense from the perspective of the person doing the stuff. Gamarra isn’t here to build up strawmen of the kinds of people you meet in the real world to take them down a notch. She is clearly trying to force us to confront the idea that bad shit happens to everyone, even people we don’t want to feel any sympathy for. That everyone makes mistakes. Big mistakes. Mistakes that hurt people we care about, possibly irrevocably. What really differentiates a “good” person from a “bad” one, if anything, it’s the desire to do better. The desire to take the pain you’ve felt and channel it into working to keep it from happening to someone else. The difference between people who struggled to pay back their student loans and wanting everyone else to suffer as much and those wanting to protect others from the hardship they had to endure. No one in this book has completely clean hands, but how they deal with the hurt they inflict on others is what really matters. The real heroes of this book are compassion and the courage to be vulnerable even when you’ve been hurt.

Last point is on tone. Despite the source material, this is not a comedy. The problems these characters face run the gamut of severe parental abuse, partner abuse, substance abuse, mental health issues and the pervasive stigma around it (including suicidal ideation), neurodiversity and the stigma around it, learning disabilities, racism, sexism, colourism, classism. We are deep in angst territory here. This can hard to read, so make sure you have the spoons. But I’ll say that for me, I couldn’t put this damn thing down, even with no real spoons available. I may have even gained a couple, what with Gamarra’s belligerent pep talk in the author’s note.