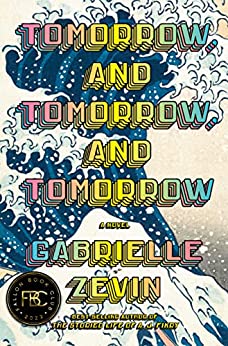

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow is the tale of the friendship between Sam Masur, later Mazer, and Sadie Green, video game-designers, business-partners, and two-thirds of the founders of Unfair Games. It was video games that brought the unlikely pair into each other’s lives to begin with. Sam is recovering from a car accident that killed his mother and permanently damaged his foot while Sadie is visiting her cancer-patient older sister when the two begin gaming in the hospital’s game room. Years later, after some bumps along the way, they find themselves in Massachusetts for college, him at Harvard and her at MIT. Sam’s drifting toward a Math degree while Sadie is taking a course in game design. When he suggests they spend the summer designing a game together, it launches their careers.

Along with Sam’s wealthy college roommate Marx they start a company called Unfair Games. Zevin describes at great length the games that Sam and Sadie come up with. They are of varying degrees of plausibility. Perhaps my favorite is Sadie’s MIT course-project “Solution,” in which the player roleplays as a factory worker striving for maximum efficiency, only to discover the disturbing reality of their work after beating the game. The duo’s first professional output is “Ichigo,” about a genderless Japanese child desperate to return home after being lost at sea.

As Sam and Sadie become more and more successful, their personal relationship suffers greatly. Sadie thinks Sam is getting too much of the credit, while Sam resents that Sadie refuses to do promo for their games and leaves it all to him. With each successive game they find it harder to work together, until eventually they stop doing so entirely. Though the conflicts between Sam and Sadie feel genuine, Zevin falls short while trying to dramatize them. She frequently resorts to sitcom-level misunderstandings and miscommunications, and she does damage to both characters by having them act so irrationally.

Zevin also has an annoying habit of inserting commentary into the narrative unnecessarily. To me, it felt like she just didn’t have enough confidence in her audience to pick up on her inferences. For instance, she belabors the point that the Ichigo game is cultural appropriation since neither of them are Japanese. (Sadie is white, while Sam is half-white, half-Korean.) In context, it’s an unnecessary intrusion of the authorial voice. At other times, Zevin breaks into the proceedings to announce, for instance, that certain characters weren’t using cell phones because most people didn’t have them at the time, or to provide a lengthy definition of the video game shorthand NPC, for non-player character. Each instance takes the reader out of the story.

Zevin deserves credit for how real Sam and Sadie feel, but the plotting devolves as the novel heads toward its conclusion. New characters and new information are introduced late in the game, and there is a total stylistic departure that strives to be innovative but is really just irritating.

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow seems to be Zevin’s attempt to tell an unconventional love story, about friends and creative partners rather than romantic partners. But her means of creating conflict is just to have her two main characters treat each other worse than most people treat their enemies. By the end, most readers will probably be hoping that Sam and Sadie keep far, far away from each other.