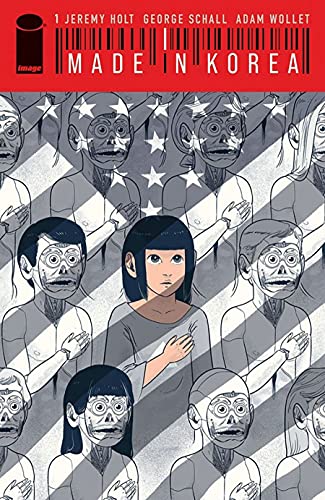

You think you are getting one story and it turns around to become another when reading Made in Korea. Yet it is still the first story! Jeremy Holt (a nonbinary author) has created a commentary on humanity, life, children, privilege, sexuality, gender and more all bottled up, ready to explode off the page. The words are complimented and enhanced by the art of George Schall. Even when there is light used, the darker overtones come into play.

You think you are getting one story and it turns around to become another when reading Made in Korea. Yet it is still the first story! Jeremy Holt (a nonbinary author) has created a commentary on humanity, life, children, privilege, sexuality, gender and more all bottled up, ready to explode off the page. The words are complimented and enhanced by the art of George Schall. Even when there is light used, the darker overtones come into play.

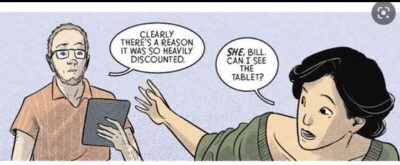

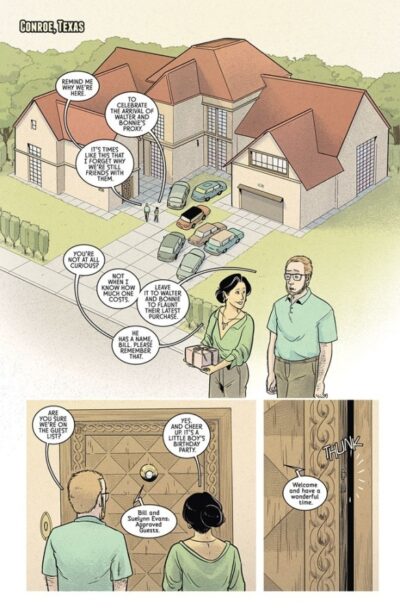

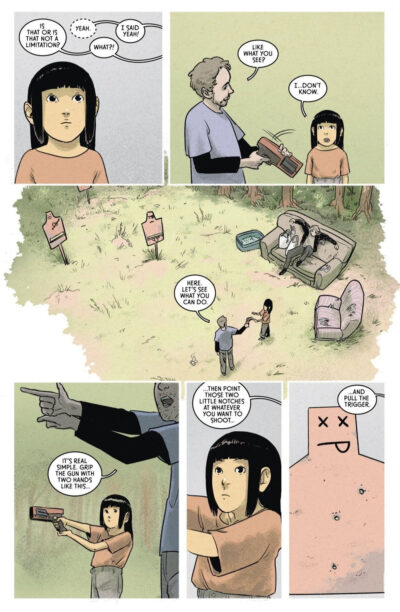

Set in the not too far future, we have had some type of plague that seems to make young children not possible (there is a hint to this, so either I missed the explanation, or they do not explore it). You can, however, adopt a robot child (or proxy). One family has adopted a boy, and as the father says to our main characters “father” it is no kin of his, but what his wife wants, she gets. But he is not too concern with rules or acknowledging his privilege. Afterall, he has guns and real ammunition (which have been outlawed for around half a century). The friend and his wife then decide to adopt their own “child” but do not realize that the robot that he (father) has called “it” and she (mother) Jesse, has a secret. You, see her creator has found a way to change these robots into something more. Just how much more, nobody knows or how potentially dangerous.

Set in the not too far future, we have had some type of plague that seems to make young children not possible (there is a hint to this, so either I missed the explanation, or they do not explore it). You can, however, adopt a robot child (or proxy). One family has adopted a boy, and as the father says to our main characters “father” it is no kin of his, but what his wife wants, she gets. But he is not too concern with rules or acknowledging his privilege. Afterall, he has guns and real ammunition (which have been outlawed for around half a century). The friend and his wife then decide to adopt their own “child” but do not realize that the robot that he (father) has called “it” and she (mother) Jesse, has a secret. You, see her creator has found a way to change these robots into something more. Just how much more, nobody knows or how potentially dangerous.

The themes of school bullies, being smart (or too smart too soon), youth, naiveness, body image, gender, the thirst for “more”, and the thirst for change (which the units are unable to do physically) is explored. Also, there is how the robotic beings can be used. Such as adult sex objects. In fact, we see how one inventor uses a bar-lounge to set up a viewing station for anything you want. A nice, dad-bod guy, a person with both male genitals and female breasts, or a very handsome young man that frankly is built like a freaking brick house.

There are several trigger issues. The theme of gender, body dysmorphia, school shooting, violence and even the somewhat casualness of the sexuality. The images also could be a tad disturbing at times. As a few of the “extra” points that seem to be incomplete. This makes me wonder if there is more to Jesse’s story. The end includes short extra stories included to enhance themes of robot vs. human and themes of life, death and other.

And while most mature teens (at least 14 and up, but I would go as far to say at least 16) can read, I am not completely comfortable recommending to teens. Know your self and your reader.