Back in 2019, I read Jonathan Drori’s Around the World in 80 Trees and was as shocked as anybody that I could truly love a book about trees. But love it I did, so much so that when I heard Drori had written a follow-up book about plants, I rushed to get my hands on a copy.

Back in 2019, I read Jonathan Drori’s Around the World in 80 Trees and was as shocked as anybody that I could truly love a book about trees. But love it I did, so much so that when I heard Drori had written a follow-up book about plants, I rushed to get my hands on a copy.

Around the World in 80 Plants follows the same format as its forerunner: Walking roughly in Phileas Fogg’s footsteps, Drori takes a trip around the world, starting in England, moving through Europe, the East Mediterranean and the Middle East, then to Africa, Asia, Oceana, and South America. He travels through Mexico and Central America before landing in the United States and, finally, Canada. Along the way, he selects plants from these regions and discusses them in various terms: Sometimes he focuses on the culture or folklore of the area (such as the use of Spanish moss in hoodoo, a spiritual offshoot of Louisiana voodoo), while at other times he addresses the importance of plants in the evolutionary record (as in welwitschia, which some botanists believe is the missing link between cone-bearing plants and flowering plants), to plants and their economic and social impact (hello, tobacco!).

As in 80 Trees, this book has a wider appeal than simply to botany enthusiasts. On one level, it simply provides fascinating stories that may come in handy for any Jeopardy fan. Case in point: If you ever need to know what flower caused a 17th century buying frenzy that eventually led to a situation not unlike the 2008 housing bubble, this book has you covered (“What is the tulip?”). Similarly, you might find intriguing fodder for cocktail parties in the story of wormwood. Sure, you may have read that Henri-Louis Penrod mixed wormwood with anise and other herbs and set up a factory to manufacture absinthe, but did you know that, prior to that, a medicinal Extrait d’Absinthe was patented by a Swiss doctor with the unlikely name Pierre Ordinaire?

Drori touches on some social issues as well, such as in the section on oil palm. After listing the many modern luxuries that people manufacture using palm oil–soap, animal feed, candles, and yummy, yummy baked goods–he points out the destruction of rainforest to set up oil palm plantations is destroying biodiversity hotspots, particularly in Southeast Asia. On the one hand, I don’t remember him indulging in this type of editorializing in his first book; on the other hand, I thought his summation of the situation was mildly disappointing, given the extreme problem palm oil plantations pose for endangered species such as the orangutan. I felt at times he was walking a line and playing it safe with his commentary, which made me wonder why he decided to go there at all.

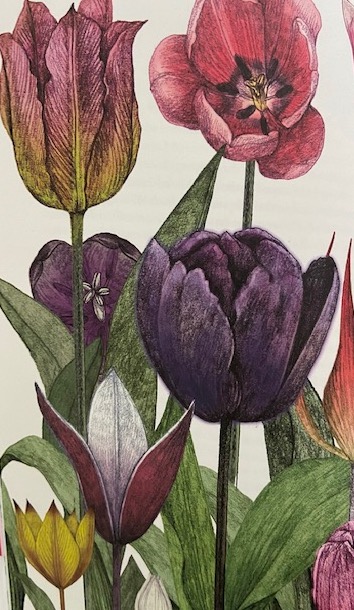

As in 80 Trees, you can’t talk about 80 Plants without praising the exquisite illustrations by Lucille Clerc. Every bit as important as the text, the illustrations alone offer a perfectly legitimate reason to purchase this book. You can lose yourself in the beauty of the water hyacinth, the damask rose, or even the prickly pear.

Here is my challenge for you: Go to a bookstore and pick up a copy of this book and leaf through it. You may just find it too difficult to put it down.

Illustrations: Top right, tulip; bottom left, mistletoe.