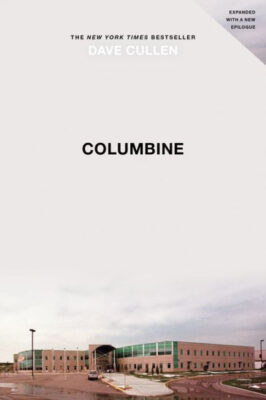

When I first saw the cover of Dave Cullen’s Columbine, it filled me with dread. The picture of the exterior of the school stretches across the lower part of the cover, while the rest of the image is nothing but a wide expanse of overcast sky. The cover is blank and cold. Some of my reaction is, of course, attributed to knowing what happened at Columbine. But there is something particularly hopeless about the cover image.

When I first saw the cover of Dave Cullen’s Columbine, it filled me with dread. The picture of the exterior of the school stretches across the lower part of the cover, while the rest of the image is nothing but a wide expanse of overcast sky. The cover is blank and cold. Some of my reaction is, of course, attributed to knowing what happened at Columbine. But there is something particularly hopeless about the cover image.

Columbine is about the 1999 mass school shooting perpetrated by Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold. While school shootings had happened before, Columbine could be pointed to as the inspiration for many mass shootings that now seem so hopelessly common. The bleak pain these constant shootings cause for outsiders is nothing compared to the agony suffered by the victims and families directly impacted by the massacres. In Columbine, Cullen rightly centers the victims as well as digs deep into the lives and minds of the killers.

Cullen debunks a few narratives. The media spread reports about the killers being extensively bullied (in fact, they did a fair amount of bullying others), that they targeted the jocks that tormented them, that they were Goths or part of some other organized group. Many myths and partial truths emerged in the weeks and months after the massacre. But the shooting didn’t happen as a reaction to any particular injustice. Cullen makes clear that it happened because Harris was a sadistic, narcissistic psychopath and Klebold was a self-loathing, suicidal depressive. Harris had long wanted to wipe out humanity. Klebold was depressed, suicidal, and furious at a world that he found ignorant and rejecting. The shooting was also not the centerpiece; it was meant, first and foremost, to be a series of catastrophic bombings. If the bombs had gone off properly, hundreds more would have died.

Cullen’s book reads like a novel. It skillfully weaves nuanced portraits of the victims with detailed accounts of the killers’ lives and thoughts. The day of the massacre is described practically minute by minute. Cullen had a massive amount of primary resources to work with. Harris and Klebold left detailed journals—Harris’ particularly focused on planning the massacre—and both he and Klebold had recorded hours of video later known as The Basement Tapes. Cullen does not paint them as caricatures of the Big Bad. Their mundanity is far more frightening.

I’ll be honest—this book was pretty terrifying. Cullen walks through the attack detail by tiny detail. He minutely describes every victim, witness, and family member—their feelings, their suffering, their resilience. He excavates the killers’ motives and personalities in just as much detail. I’ve read a lot of books about crimes. Nothing comes close to the power of this book.

Cullen wrote an epilogue some years after the book’s initial printing. In it, he talks about his own experience of reporting, researching, and ultimately writing a book about the massacre. It’s a very personal account and one I appreciated. He was not separate from the story, but connected to it through his relationships with the victims’ families and other survivors. He was emotionally and psychologically impacted by his involvement, and that truth, added to all the others he offered in Columbine, gives additional weight to a brilliant account of a horrifying event.