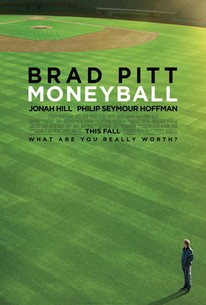

I know far more about baseball than someone with my level of interest (mild) should. I have favourite players (Mookie Betts and Corey Seager), a lot of thoughts on player hair and facial hair (Cody Bellinger’s haircut, Seager’s unfortunate ‘goatee’) and I even know the team’s GM (Dave Roberts). In short: I live with a baseball fanatic (Dodgers fan, obviously) and have essentially absorbed these things, osmosis style from the many, many games that play in the background to my daily life during baseball season (so.many.games in a baseball season). All of which is to say: when looking last week for a sportsball book to hit the Cannonball read bingo square, there was no shortage of sports books lying around for me to choose from. I chose Moneyball because I really enjoyed the other Michael Lewis books I’ve read and it gives me an excuse to watch the Brad Pitt movie version again.

Michael Lewis is writing the very old human story of ‘why don’t good ideas travel’, and setting it in a baseball stadium (the Oakland Athletic’s stadium to be particular). Unsurprisingly given his background in economics, he is fascinated by how the baseball ‘market’ doesn’t seem driven by efficiencies the way that other markets are, except for a few select baseball teams (the A’s and, at the time of writing in 2002, a more nascent movement within the Toronto Blue Jays). To tell this story of market inefficiencies, he focuses on a few key characters: Billy Beane, the General Manager for the A’s, and a few of the key ‘misfit’ players that Billy and his stats wonk, Paul dePodesta, have identified as being undervalued (Jeremy Brown, Scott Hatteberg, Chad Bradford).

Lewis is not unaffected by the romance of baseball- when he describes sitting in the back offices with management during A’s games, he is swept up in the game the way that most fans are. What most of his book does- is a testament to, really- is the power of numbers and statistics in putting together a team, rather than romance (i.e. statistics about getting on base should be more important than whether a player looks like a ball player). Again, at the time of writing (2002), this stats lesson is one that Billy and Paul have learned but the rest of MLB has not, so the A’s are looked at oddly by the rest of the baseball insiders that make up the baseball microcosm.

As per usual in the ‘why don’t good ideas travel’ story, the answer is ‘vested interests’. There are a lot of surrounding players in the ecosystem (scouts, commentators, former players) who all believe in their ability to divine which players are good or will be good, or what the right strategy should be (‘manufacture runs’ rather than waiting for them to come to you). If statistics are all you need, then the value of all of these hangers-on drops significantly- who needs an army of baseball scouts with their ‘keen eye for talent’ if you can get better results from one wonk with a laptop? Although you can tell this story as a battle between the idea of baseball (what a player and a game ‘should’ look like, with all the nostalgia that this idea implies) and the reality of baseball (what a player looks like ultimately matters less than whether they get on base/ score runs), the vested interest theory puts another layer beneath that.

I’m laying it out bluntly and Lewis, as always, tells it in a more nuanced an entertaining way. I thought I might have to abandon ship in the tough early stats section (the Bill James baseball stats section was where my going was roughest), but once he swings back to telling the stories through the lens of the ‘misfit’ players, I was back in my seat. I can’t wait to watch the movie again.

Play ball- sports ball! cbr13bingo