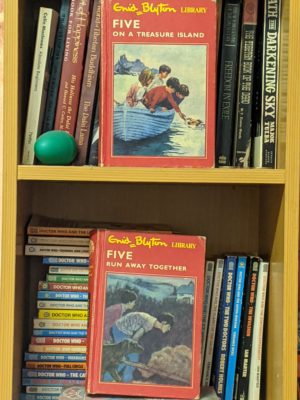

CBRBingo: Free! (birthday gift); Shelfie

I rescued these books from the garage sale my brother and I were holding after clearing out our childhood home following the death of our father and out mother’s move to aged care. I was flying back home afterwards, so needed to be selective with the mementos I would take with me. I almost let these go, but I got them from my parents for my tenth birthday and loved them so much as I child that I took them back.

There are six books in the set. I chose these two to reread and review because they are the first one in the series, and the first one I read, my first experience that I can remember of reading books out of order and hearing the callback to previous events before the events themselves.

These books have not aged well, in so many ways. This was no surprise, as they were already well out of step with the times when I first read them in the 70s, and I have read that they were considered somewhat old-fashioned when written in the 1940s.

They are awash with misogyny, which chimed with my own internalised misogyny as a child. Of course cousin Georgina would rather be Master George and do fun, active boy things than be a proper little housewife like pathetic little Anne, the youngest of the children who was a timid little blabbermouth who loved doing the washing up. Of course she would be so proud when her father proclaimed her “as good as a boy” when she and her cousins foiled the criminal plans of those who tried to take Kirrin Island from her.

The class issues went over my child head, but are so obvious as an adult. George’s family have come down in the world, with her mother now only owning a large house, a nearby farm and an island. Uncle Quentin’s important science books that he writes at home in his study with no visible university affiliations are ever so important (important enought to see him kidnapped multiple times throughout the series), but don’t make much money. So they are so poor that they only have one servant and can’t afford to send George to a proper boarding school. Isn’t it lucky that the children find all those gold ingots from the family’s glory days?

The working class people are properly subservient like fisherboy Alf and and fat Joanna the housekeeper, or clearly villainous like the Stick family of Five Run Away Together – surly cook Clara, her sly, stupid and spotty son Edgar, and dodgy husband. Even their dog is mangy and stinky.

Luckily there are no people of colour in these volumes, so I was not slapped in the face by the casual racism so incisively parodied in Five Go Mad in Dorset. But the “lashings of ginger beer” trope of that spoof is ever present, with lengthy descriptions of the food that the children love to eat contrasted with the poor fare served up by Mrs Stick, an early clue to her villainy. Clearly this was food porn for the deprived English children of the wartime and postwar rationing era.

So what’s to love about these books? The sheer fantasy of plucky, independent children having exciting, dangerous (but not dangerous enough for anyone to get seriously hurt) adventures, free of adult supervision and constraints. Who wouldn’t want to be an eleven year old girl exploring her own island with a ruined castle with her admiring cousins? What child wouldn’t want to be able to easily foil villains, prove they know better than their parents, and be celebrated as brave and clever? And maybe even, as good as a boy? I sure did, and part of me still does.