Kate and her husband Dan need a fresh start, not least to save their marriage. So they move into Kate’s brother’s house to look after it, which is one of only 6 houses that form a little community (Greenloop) situated in the middle of nowhere. Greenloop provides its inhabitants with a high-tech standard of living, while being close to nature (and just a 90 minutes drive from Seattle).

Soon though there is trouble in paradise. Rainier erupts, and while it’s too far away to be of any immediate danger to the Greenloop inhabitants, the devastating aftershock reaches all the way over there. The community gets cut off by a river of mud and there is no way to call for help. Rescue workers are busy elsewhere, and they probably don’t even know Greenloop needs help. And wild animals, both prey and the predators that are after them, are driven away from Rainier and towards Greenloop…

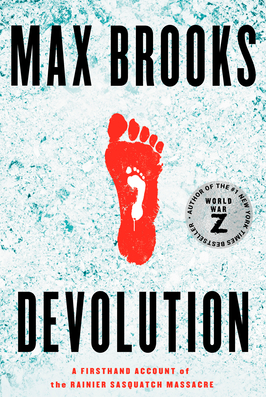

Devolution is written in the same format as the book that made Max Brooks’ famous: World War Z. A personal account of the events takes up most of the book, while the rest is made up of interviews with experts and relatives. This is not a format that I usually enjoy as I find it takes me out of the main story and it can sometimes be too dry. It feels too much like a gimmick. However, in this book it is Kate’s diary that carries the story and it does so to such an extend that the “interruptions” are not distracting.

The plot itself was a little slow to get into at first, but once it did, it absorbed me completely. The premise is very silly but if you suspend your disbelief it’s a lot of fun.

Did I write fun? I meant gruesome, violent, dark. But in an entertaining way. The setting of the story, the community of Greenloop, felt claustrophobic. How can a community built in the middle of a vast wilderness feel claustrophobic? But it does, if you consider that the characters can’t really leave their homes, because this vast wilderness is hostile and full of dangers. The woods close in around them. The creatures are ever closer, witnessing the humans’ every move.

Our protagonist, Kate, is a meek, neurotic character in the beginning but she grows to be a survivor. And the point the book is trying to make, I think, is that you can’t pretend to be part of nature from the comfort of your own high-tech house. When push comes to shove, when you are exposed to the elements and attacked by wild animals, will you be able to adapt and protect yourself? Or will you still look at those wild animals and think they’re just like Disney characters?

Being close to nature is, I believe, of paramount importance if we are to save ourselves in the face of climate and other disasters. If we keep being as detached as we are today, staying as far away from it as possible, using our smart phones and smart cars and smart homes to shield ourselves against it and forget it even exists, there is a risk that we might also forget how vulnerable we really are. Our civilisation places blind faith into technology, that it can solve all the problems we cause, but the truth is that our solutions are fragile, buckets to catch the water from leaking roofs that are about to fall onto our heads. But being close to nature isn’t about going to a zoo to look at the cute animals or going for a walk around the park downtown. It is about respecting how much greater than us nature is and how we are but one piece of a much larger puzzle.