CBR13bingo Uncannon

CBR13bingo Uncannon

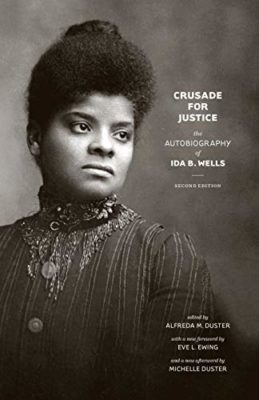

Ida B. Wells is one of the most important and influential civil rights crusaders in US history, and yet I never learned her name in school. Born into slavery, orphaned as a teen, she became a world-renowned journalist who devoted her life to fighting US lynching laws of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, exposing the truth about the victims and perpetrators of these heinous acts. As she fought to educate the world about the plight of Blacks in the US, she found surprising allies and enemies. Much of the resistance she faced will sound familiar to anyone involved in social justice struggles today. Ida B. Wells’ unflinching dedication to the truth and to justice make her a true American hero. You should know her name.

Ida B. Wells was born in Mississippi in 1862. She and her parents had been enslaved, and after the Civil War, her father worked as a carpenter. In 1878, Wells’ parents and a younger sibling died in a Yellow Fever outbreak. At the age of 16, Ida B. Wells took charge of the care of her younger siblings and supported them by working as a teacher for a time and then by writing for Black newspapers which were often published by Black churches. Wells eventually wound up in Memphis, Tennessee where her life would take an important turn. Wells took a position at the Free Speech newspaper in 1889 and became a part owner of it. In 1892, three black men who owned a successful grocery store in Memphis were lynched. They had defended their business against an angry white mob and were brutally murdered. Wells made it her mission to find and report the facts of this lynching. When it became clear that there would be no justice toward the white perpetrators of this crime, Wells used her voice at the paper to encourage the Blacks of Memphis to boycott the streetcars. The boycott hurt the city and led to anger against Wells and her community. Many Blacks left Memphis for the west, thinking to build a new life in the newly opening Oklahoma territory. Wells’ newspaper was attacked and destroyed while she was in New York, so she took a job with New York Age and did not return.

Wells’ investigations focused on lynchings in the US, and she would travel all over to report on the horrors visited upon Black people in the name of “justice.” Her reporting was detailed and factual, and her objective was to take apart the racist white argument for lynchings, i.e., that the victims of lynchings were criminals “guilty” of sexual crimes. The idea that mobs were defending women’s “honor” garnered them sympathy up North and outside the US. Wells compiled statistics showing that this was not the case and published a booklet, The Red Record, demonstrating the falseness behind these claims. Some churches and philanthropic groups supported Wells’ anti-lynching crusade, but in order to put more pressure on both state governments and the federal government, Wells went to England. By raising awareness there amongst churches and other philanthropic societies, she hoped to put pressure on the powers that be in the US to make changes and to ensure equal treatment under the law for all US citizens. Wells did have success on her two visits to England. She was covered in the major newspapers there and drew large crowds who were appalled to learn the facts of how Blacks in America were being brutalized in the most lawless and barbaric ways. While this did get Wells and her cause more attention back in the US, it also exposed divisions among so called “allies” in the work to ensure freedom and justice for all.

When she returned to the US, Wells continued her investigative reporting on lynchings, but she also found herself involved in many different grass roots organizing efforts. Her English allies had encouraged her to organize Black people in the US to advocate on their own behalf. Much of what she records about this grass roots work in her autobiography sounds like it could have been written today. Women’s clubs were popping up all over the country, including clubs involving Black women. These clubs were philanthropic, civic minded groups, and they often tried to work together on common causes. Wells advocated for anti-lynching statements to be issued by these groups both locally and nationally, and while she had some success, her description of the work exposes some fundamental underlying problems. First, a number of white women “allies” seemed to resent Wells’ outspokenness when it came to working with southern women’s groups. Wells had written and spoken forcefully about the hypocrisy of Christian groups that refused to protest the evils of lynching and the barbaric treatment of Blacks because they were afraid of losing white southern support for their other agendas. Sadly, Susan B. Anthony is an example of this way of thinking, and Wells knew and worked with Anthony on suffrage. Moreover, a number of prominent women believed the racist lie that Black people were intellectually sub-par and morally deviant. In addition to this division among women, Wells faced pushback from within the Black community itself. Some did not support Wells’ agenda regarding the highlighting of lynch laws, others took exception to her campaign to set up YMCA-type accommodations for the many Black people moving to Chicago, where Wells and her family lived. Others in Chicago were working on their own similar types of work, and, as anyone who has worked on a committee knows, having common goals does not mean that everyone gets along and works well together.

Nonetheless, Wells tirelessly worked to find money for community projects, while also traveling to report on lynchings and speaking at national events. She did all of this while also raising her children with her husband, attorney Ferdinand L. Barnett, in Chicago. Wells’ frustration often comes to the fore in her autobiography, as well it might. Certainly, there is the disappointment she felt regarding the Black community which, in her opinion, did not unite and fight hard enough against the laws that so brutalized them. Then there is the pain of being misunderstood and targeted by those she considered allies. And the political situation in Chicago, where the Black vote played an important role, also angered Wells, particularly when white politicians did not follow through on promises made in return for Black support. By far though, the continued murder of Black citizens with the passive if not active support of authorities motivated Wells to continue her work, even when she felt she stood alone.

When Wells died in 1931, she had not yet finished this autobiography, begun at the request of an admirer who wanted to know Wells’ story. Wells’ daughter Alfreda Duster edited the autobiography but could not find a publisher for it until 1971. Wells’ great-granddaughter Michelle Duster provides an afterword in which she details her family’s continuation of this matriarch’s work. It’s clear from the tone of the work that Wells was both proud of and frustrated by the work to which she dedicated her life. “Nevertheless, she persisted” would make an apt motto for her.

After reading Ida B. Wells’ autobiography, I was curious to read some of her other writings. As it turns out, two publications that feature prominently in the autobiography are readily available to readers today: The Red Record and The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition. The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States (1895) was critical to Wells’ early success as a journalist and activist. She knew that in order to win over audiences, especially white listeners, she would need to be factual and rational in her presentation of lynching. With praise and support from no less than Frederick Douglass himself, Wells went through statistics for the years 1893 and 1894, statistics supplied by white authorities themselves, to show the outrageous numbers of murders that white mobs committed against Black people in the name of “justice.” Using information from reputable newspapers, she has names of victims, dates, and the alleged “crimes” committed, ranging from murder and rape to wife beating and insulting whites. Wells shows that this vigilante justice is disproportionately visited upon Black people (there’s no record of Black mobs going after whites for crimes), that the forms it takes are cruel and gruesome (beatings, hangings, even burning alive), and that the perpetrators are almost never brought to justice. Wells makes a point of saying that she is not arguing for the innocence of all the victims, but that in a country that is supposed to be ruled by law, the accused should be afforded a fair trial and just punishment. This was clearly not happening for Black people. The specific incidents described are horrifying and the fact that Wells could provide both eyewitness and newspaper accounts of them made them even more shocking to audiences in England, where some had refused to believe that such atrocities could occur in the United States.

After reading Ida B. Wells’ autobiography, I was curious to read some of her other writings. As it turns out, two publications that feature prominently in the autobiography are readily available to readers today: The Red Record and The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition. The Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States (1895) was critical to Wells’ early success as a journalist and activist. She knew that in order to win over audiences, especially white listeners, she would need to be factual and rational in her presentation of lynching. With praise and support from no less than Frederick Douglass himself, Wells went through statistics for the years 1893 and 1894, statistics supplied by white authorities themselves, to show the outrageous numbers of murders that white mobs committed against Black people in the name of “justice.” Using information from reputable newspapers, she has names of victims, dates, and the alleged “crimes” committed, ranging from murder and rape to wife beating and insulting whites. Wells shows that this vigilante justice is disproportionately visited upon Black people (there’s no record of Black mobs going after whites for crimes), that the forms it takes are cruel and gruesome (beatings, hangings, even burning alive), and that the perpetrators are almost never brought to justice. Wells makes a point of saying that she is not arguing for the innocence of all the victims, but that in a country that is supposed to be ruled by law, the accused should be afforded a fair trial and just punishment. This was clearly not happening for Black people. The specific incidents described are horrifying and the fact that Wells could provide both eyewitness and newspaper accounts of them made them even more shocking to audiences in England, where some had refused to believe that such atrocities could occur in the United States.

Wells describes what she sees as “three distinct eras of Southern barbarism” and three excuses that they have offered for murdering Black people. First, immediately after the Civil War, lynching was excused as being necessary to forestall “races riots.” Never mind that there were no examples of “Negro insurrection”. Next, when Black men received the right to vote during Reconstruction, the reason for murder was to prevent “Negro domination.” The federal government gave Black men the right to vote but no protection of that right, leaving Southern states free to place excessive restrictions on voting and participation in government, which is exactly what racists are trying to do across the US today. Finally, the third era, the one in which Wells was writing, was the “honor” killing to avenge imagined assaults on white women. Wells points out that it is actually white men who have assaulted Black women throughout history, and she wrote that on those rare occasions when it was discovered that Black men and white women had had relations, they were in fact consensual and secret. This argument got her into a lot of trouble with both Southerners who were unsympathetic to her cause and with many white women of the North and South who believed that Black men were predators and barbarians. Wells points out that Southern men were content to leave their women and children on the plantations with enslaved Black men during the war, and there were no reports of raping going on, so their argument does not hold water.

Wells writes that whenever she lectures on lynching, she is asked what people can do to help the anti-lynching cause. At the end of The Red Record, Wells provides this list of things allies can do:

- Spread the facts

- Encourage Christian groups to condemn and protest lynching

- Don’t financially invest in places where lynching goes unpunished

- Think and act independently

- Support the house resolution that would investigate and report on 10 years’ worth of assaults on Black people

It’s sad and shameful that so many of those still apply today. The US still has no anti-lynching law.

The Reason Why the Colored American is not in the World’s Columbian Exposition (1893) is another searing indictment of the institutional racism and murderous violence that oppressed Black people despite emancipation. The World’s Columbian Exhibition of 1893 was a world’s fair held in Chicago to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Columbus’ “discovery” of America. The federal government set aside a sizable amount of money for this Expo and President Harrison named “commissioners” from every state to help with the planning. States also had planning committees, as did women’s groups. Not one single entity included Black people in the planning, nor were the achievements and progress of Black Americans, who accounted for one eighth of the US population, included in the event. Given that it had been fewer than 30 years since the end of the Civil War and emancipation, leaders of the Black community expected that a country that prided itself on equality and democracy would welcome their input and want to highlight their achievements. Not only were Blacks not included in national planning commissions, their suggestion of simply adding an exhibit with statistics demonstrating their progress in 30 years was also rebuffed, and the exposition site in Chicago would not hire Black people to work at the event. The details of this are presented in the final chapter of The Reason Why by Ida B. Wells’ husband F.L. Barnett. It was only thanks to the Republic of Haiti, which named Frederick Douglass to be its commissioner for the Expo, that there was any Black American representation at the Expo at all. Wells, Douglass, Barnett and I. Garland Penn put together this booklet and had 20,000 copies printed so that visitors to the Expo would learn not only about the progress of Black Americans but also about the racism, violence and hypocrisy that Blacks experienced. As the Expo was an international event, this meant that their story could reach more people outside the US who might then exert pressure on federal and state governments to ensure real justice for all Americans.

Each chapter in this pamphlet is full of shocking information that sounds too much like what we still see happening in the US today. Frederick Douglass wrote the introduction, in which he provides a litany of the ways in which the US has not fulfilled its ideals in relationship to Black Americans. Douglass does not use the word “erasure” but what he describes could be termed as such. Americans have forgotten that Blacks contributed to winning the war, that they have citizenship and voting rights protected by law but that these rights have been blunted by state laws and judicial decisions. I. Garland Penn’s chapter “The Progress of the Afro American Since Emancipation” provides data on achievements in education, professions, the arts and more.

Ida B. Wells penned three of the chapters: Class Legislation, Convict Lease System, and Lynch Law. As usual, she writes powerfully about Black people being emancipated but provided with no means of support afterward and left to live amongst the very people who did not want them to be free and who owned all the land and wealth. These white southerners, who always considered Black people as property and not fully human, now felt no compunction about killing them for things like “insolence”, and they faced no repercussions. They were the law and could manipulate legislation to prevent Black people from voting, intermarriage, access to education and work, etc. Moreover, they ensured the perpetuation of slavery through the convict lease system, arguing that they couldn’t afford to build prisons. Instead they hired out convicts to railroads, mines and so on. Wells addresses the inequities of the judicial system, the over-representation of Black people in prisons, and the failure of religious, moral and philanthropic agencies to help. As ever, Wells has statistics and facts to prove her points.

Having spent the last week or so immersed in Ida B. Wells’ writings, I find myself angrier than ever. I’m angry that her important work and contributions to American democracy have been erased from textbooks. I’m angry that the problems she saw and fought so tirelessly are still evident in the United States today. Being angry doesn’t get us anywhere though, so if you feel the same way, consider supporting the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund (Ida B. Wells was one of the founders of the NAACP) and the Reverend William Barber’s Poor People’s Campaign. And pay attention to what your local school board is doing regarding the curriculum.