I am on a journey to rediscover science. It’s one of those things that I found fascinating as a kid and deathly boring as a subject in school. A few months ago I picked up The Great Unknown by Marcus du Sautoy, a scientist whose job is to make scientific thought accessible to the public, and found the boredom, combined with the frustration at who du Sautoy featured prominently and who he didn’t (spoiler alert: it’s women and people of colour, they haven’t done a thing for science apparently). So I abandoned it. And then I got a message from my father in law saying he’s been cited in a book that combined ecology with Indigenous natural plant knowledge. I’ve been fortunate enough to receive teachings from Anishinaabe Elders on a number of occasions and have always come away feeling literally fuller, so I decided it was worth a shot.

I am on a journey to rediscover science. It’s one of those things that I found fascinating as a kid and deathly boring as a subject in school. A few months ago I picked up The Great Unknown by Marcus du Sautoy, a scientist whose job is to make scientific thought accessible to the public, and found the boredom, combined with the frustration at who du Sautoy featured prominently and who he didn’t (spoiler alert: it’s women and people of colour, they haven’t done a thing for science apparently). So I abandoned it. And then I got a message from my father in law saying he’s been cited in a book that combined ecology with Indigenous natural plant knowledge. I’ve been fortunate enough to receive teachings from Anishinaabe Elders on a number of occasions and have always come away feeling literally fuller, so I decided it was worth a shot.

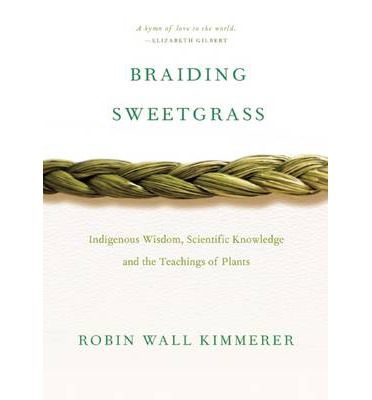

Can a book about science make your heart feel full? Apparently. Kimmerer seems to walk through life with the same overwhelming sense of gratitude that I feel navigating the world, but unlike me, she’s been able to find the language to express it fully in a way that is beyond inspiring.

People who expect the traditional scientific text here will invariably be disappointed. Kimmerer weaves many stories of her family history, of the Potawatomi Nation, of Indigenous peoples in the US (though the stories are not unique among other Indigenous peoples’ encounters with colonial powers) into a narrative about how she came to discover the vitality of a traditional way of knowing, despite her education and work in western universities. This book is not chock full of scientific facts. There are no equations or taxonomies or latin terminology. It seems to me that what Kimmerer hopes to accomplish with this book is to spark genuine interest in learning rather than overwhelm you with facts.

I think this is a part of a larger shift happening. I’m also part way through Entangled Life, a book written by a far more traditional scientist, but a book that also shimmers with a kind of poetry you don’t often associate with objective scientific thought. Still, the objectivity is there, it just looks different because the observers care about the parts of the world that they are observing. They aren’t looking for the sake of it, they are looking to understand, to connect, and these desires does not come from a desire to control.

Braiding Sweetgrass is a beautiful love letter to learning and a reminder that truly understanding something requires more of us than our education typically offered. And if you can get it, do the audiobook. It is read by the author and she infuses so much emotion into the words that I fear might be missed in text.