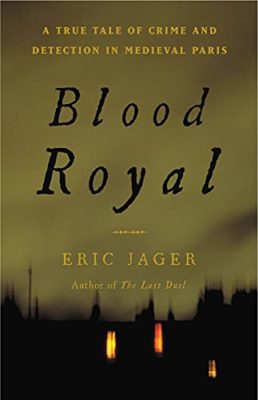

The best books about history capture what is was like to live in a particular place in time, leaning into the essential and unchanging humanity of, well, humanity. In Eric Jager’s Blood Royal (2014) it’s easy to relate to figures such as the landlord who inadvertently rents a house to unsavory characters or a woman soothing her baby who witnesses a crime. Jager even helps us relate to the person on which he focuses: the provost in charge of law and order in 15th century Paris, Guillaume de Tignonville, a man with title and power who is nevertheless not untouchable, and a man subject to the whims of the French royal family and various dukes.

Relying on a recently discovered scroll, Jager tells the story of the murder of the Duke of Orleans and de Tignonville’s meticulous detective work, in which he was, according to Jager “rather ahead of his time” (meaning he investigated thoroughly and did not resort to torture). The early parts of the book are the strongest, capturing the day-to-day life of Parisians as well as how de Tignonville looked into what was a shockingly violent murder of one of the most powerful people in Europe at the time. Orleans’ murder was particularly consequential because he was the brother of the mad King Charles VI and served on a regency council when the king was incapacitated.

Relying on a recently discovered scroll, Jager tells the story of the murder of the Duke of Orleans and de Tignonville’s meticulous detective work, in which he was, according to Jager “rather ahead of his time” (meaning he investigated thoroughly and did not resort to torture). The early parts of the book are the strongest, capturing the day-to-day life of Parisians as well as how de Tignonville looked into what was a shockingly violent murder of one of the most powerful people in Europe at the time. Orleans’ murder was particularly consequential because he was the brother of the mad King Charles VI and served on a regency council when the king was incapacitated.

The aftermath of de Tignonville’s investigation is unsatisfying, which is not Jager’s fault. He discovers that Duke John of Burgundy (called “John the Fearless” due to his prowess on the battlefield) ordered Orleans’ murder, angry that he had lost power due to Orleans’ control of the regency council. But, stymied by John’s popularity in Paris, the king’s mental illness, and the other dukes’ indecisiveness, John successfully rehabilitated his image by framing the murder as tyrannicide. For decades the conflict between Burgundians and Orleanists simmered, eventually leading an opportunistic England to reignite the Hundred Years War. It’s a messy end to what had been a tidy detective story–but that is history. Returning to the scroll to conclude the story, Jager notes, “This is a story of everyday life and an extraordinary crime. Centuries later, they speak to us: the baker and the broker, the water carrier and the florist, the interrogator and the carpenter’s apprentice–and, of course, the provost himself.”