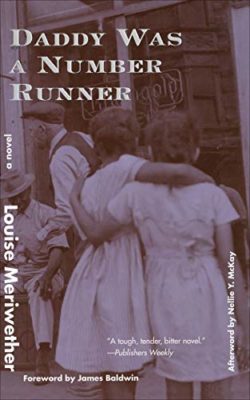

As I started to write this review, I did a little search on Louise Meriwether and it turns out the NYT ran a story on her today. I first heard of Meriwether only recently, which seems to be a common story despite the fact that Meriwether’s much lauded first novel Daddy Was a Number Runner was published in 1970. Did you know that there is a prize in her name? The Louise Meriwether First Book Prize

As I started to write this review, I did a little search on Louise Meriwether and it turns out the NYT ran a story on her today. I first heard of Meriwether only recently, which seems to be a common story despite the fact that Meriwether’s much lauded first novel Daddy Was a Number Runner was published in 1970. Did you know that there is a prize in her name? The Louise Meriwether First Book Prize

…was founded in 2016 to honor author Louise Meriwether by publishing a debut work by a woman or nonbinary author of color, between 30,000 and 80,000 words. The prize is granted to a manuscript that follows in the tradition of Meriwether’s Daddy Was a Number Runner, one of the first contemporary American novels featuring a young Black girl as the protagonist. Meriwether’s groundbreaking text inspired the careers of writers like Jacqueline Woodson and Bridgett M. Davis, among many others. The prize continues this legacy of telling much-needed stories that shift culture and inspire new writers.

James Baldwin wrote the Foreword to Daddy Was a Number Runner, and in it he wrote, “At the heart of this book, what gives it its force, is a child’s growing sense of being one of the victims of collective rape — for history, and especially and emphatically in the black white arena, is not the past, it is the present.” This book, now over 50 years old, with a focus on a twelve year old girl living in Harlem in the mid-1930s, provides the point of view of that girl as she begins to see her family, friends and neighborhood with the eyes of a child becoming an adult. Much of what she sees in 1934 has been seen repeatedly in US history up to today, and it is a grim reality indeed.

Francie Coffin lives with her mother, father and two older brothers in a rundown flat in Harlem. The building, like those around it, is infested with rats and bugs. Work is hard to find, but Francie’s father is a number runner. He works for a local boss (who works for gangster Dutch Schultz) who runs a kind of local lottery/gambling game where people bet on numbers with a chance to win a jackpot of several or perhaps hundreds of dollars. Number running is illegal, but local cops, the mayor, etc are all in on the take, so it is unusual for someone like Francie’s dad to get in trouble. Everyone, including children, plays and dreams of hitting big. The lottery is a diversion from the hard life that people are living during the depression and made worse by the fact that their skin is Black. Francie goes to school and is a pretty good student, but the white teachers aren’t encouraging of their pupils and seem afraid of them. Francie’s older brother Junior skips and has joined with a gang called the Ebony Earls, a fact that upsets and angers her parents. Her other brother Sterling is a good student with a talent for chemistry but little opportunity to advance in that area. Francie’s friends and neighbors are all in the same boat. Work is episodic at best and support is practically nonexistent. When the Coffins do get government support, the social worker assigned to them is condescending and seems to delight in taking support away at the first opportunity. The neighbors, however, try to look out for one another and give what they can to each other when in need.

The story is about a year in Francie’s life in which she begins to grow up. Both her body and her understanding of how the world works will change. She will lose her childish body and her naïveté as the reality of the world in which she lives begins to become apparent to her. One thing that the reader learns quickly is that black girls are treated as sexual objects by men, especially the white men in the neighborhood who run the shops. They frequently grope Francie and then give her a little extra food or some coins. Francie has not completely figured out how sexual intercourse works but she is learning in part thanks to her friend Sukie whose older sister is a prostitute. Reading about the perversions that grown men visit upon Francie is sickening but it also demonstrates how black girls are treated as “women” or as somehow not being children but as sexual objects. That’s a problem that seems to never go away.

Francie’s relationship with her father and her view of him is central to this story, and that perception changes in significant ways over the year. Francie adores her dad; he is tough with his sons but sweet to her. He also plays piano and makes extra money doing so. What we and Francie see over the course of the year though is that circumstances can wear a man down, and that Mr. Coffin is all too human. Mr. Coffin prides himself on taking care of his family and his wife not having to work, but the family’s increasingly dire finances will force a change in that area, and that change will have an impact on relationships within the family. It takes Francie much longer than her older brothers to see what is happening.

While Francie is experiencing these personal changes and upheavals, the upheavals of the outside world also effect her life, and they could have been taken from today’s headlines. Francie’s brother Junior and some of his fellow gang members are arrested for murdering a white man, with the police using torture to extract confessions from them. Harlem also experiences protest and clashes with the police over the Scottsboro case (in which black teens were accused of raping white women and sentenced to death). Police violence against black teens for suspected criminal activity (never proven) comes up several times in the book, and immediate violence against those children is the norm.

In the original NYT review of this book by Paule Marshall described it as episodic and that this was a weakness, but I think Meriwether’s way of storytelling provides a snapshot of history as it repeats itself over and over and over again. Seeing the world through Francie’s eyes as she gradually figures out what is going on around her is powerful and tragic. The final scene with Francie and her brother Sterling is one of the saddest I’ve read — where childhood dreams crash into the brick wall of reality. The fact that Meriwether (still alive and a COVID survivor) is not as well known as she should be is, I guess, not surprising, nor is the fact that the story she tells from 50+ years ago could still be told today. It seems a very appropriate novel to review on Juneteenth.