Keiko Furukura has been different her entire life, and she’s always to understand why she makes people uncomfortable. As a child, she found a dead bird and she brought it to her mother, who responded with sympathy and an offer to bury it. Keiko instead wanted to eat it. One day at school, two boys were fighting. Horrified, one of the girls screamed for someone to break them up, so Keiko grabbed a shovel and hit one of them over the head.

Keiko Furukura has been different her entire life, and she’s always to understand why she makes people uncomfortable. As a child, she found a dead bird and she brought it to her mother, who responded with sympathy and an offer to bury it. Keiko instead wanted to eat it. One day at school, two boys were fighting. Horrified, one of the girls screamed for someone to break them up, so Keiko grabbed a shovel and hit one of them over the head.

And that was her life until she got the job working at the convenience store. Now, in her mid-30s, she’s basically figured out her routine in life. Her sister helps guide her through interactions with other people, and she models her dress and speech patterns after co-workers. On her first day working at the convenience store, she was given a corporate employee manual, and it’s become her Bible. At the beginning of her shift, the manager has them practice phrases they can use to greet customers. There’s an easy routine to her life, and it’s given her purpose and comfort. The store is her entire life. She even dreams of the store.

Keiko is also a virgin, and has not only never wanted to have sex, but is quite happy with that fact. Not that anyone would believe that if she gave voice to her feelings. That she’s never been in love is shocking to the few acquaintances she has, and people insist that she either stop working and find a husband, or get a better job. They can’t imagine that she’s actually content with her life.

One day, her manager hires a shiftless man named Shirahara. He’s never been able to hold a job, is unpleasant, and is a terrible worker. He’s also incredibly condescending, sexist, and dismissive of everyone around him.

I’m not going to give away the whole book – but if you think this ends in them bonding over their weirdness and falling love, don’t. This isn’t that kind of story.

No diagnosis is ever given for the characters (I don’t think that’s the point), but Keiko is (in my totally unqualified diagnosis) probably on the autism spectrum, and is definitely asexual. I’m not sure what’s wrong with Shirahara – but he seems like an hikikomori.

For those who’ve never heard of hikikomori, it’s a phenomenon first diagnosed in Japan in the 1990s, characterized by extreme and persistent social isolation that can last decades. The rise in hikikomori followed a florescence that saw massive economic growth. By the 1990s, Japan’s home entertainment-centric tech economy became stagnant, and millions of young Japanese were left out of the wealth the previous generation had seen. This left so many of them feeling lost and unsuccessful, and they began turning inwards – cutting themselves off completely from social interaction. The rise of the internet made this even easier, as many became obsessed with online life.

It’s thought that there are at least one million hikikomori in Japan, and though they are typically thought to be young people, this isn’t restricted to any particular age group. The hikikomori phenomenon is starting to show up in other countries, as well, including the United States. Which makes sense, given the economic hardship and political indifference impacting the lives of so many young Americans.

Shirahara wants nothing more than for society to forget about him. It’s not so much that he wants to die, it’s that he wants to be left alone. He wants a wife – not only so someone will fulfill his sexual needs (his fulfilling someone else’s sexual needs never seems to cross his mind), but so society will stop bothering him. But he is absolutely not a sympathetic figure. He is very abusive towards Keiko, and even though Murata does a great job making us understand the pressures weighing him down, Keiko (this book is told from her perspective) has absolutely no tolerance for his abuse and attempts to do to her what society has done to him. There are strong incel vibes from Shirahara, but he isn’t quite at the point of murdering women.

So that’s good for him, I guess.

He kind of pulls Keiko into his worldview because she thinks she needs to be “cured” of her weirdness. Not for her sake – she’s content – but for the sake of her parents and sister, who have suffered greatly over her inability to just be normal. She repeatedly describes herself as a cog in the machine of society. When the cog breaks, you throw it away so that the machine can continue working properly. She’s been able to fake being a working cog for her entire life, but she’s begun questioning whether or not she can still do that.

This book is, to some degree unknown by me, autobiographical. Published in 2016, Murata was a 36 year-old writer who worked at a convenience store for most of her adult life. She worked part time while writing this book (her 11th), and continued working there after it was published, before having to quit due to an obsessive fan who began visiting her regularly. She grew up in a conservative home where she was taught from an early age that, as a girl, she should “learn to cook or something”. Her brother, conversely, had a great deal of pressure put on him to become a doctor or judge. Murata also recounts a time when she came across her brother’s collection of erotic books, and how the objectification of women horrified her. These differing expectations placed on her and her brother are reflected in the ways Keiko and Shirahara view society. Shirahara is crushed by the pressure to be something, while Keiko is seen more as a disappointment because she has nothing to offer a man.

Murata’s writing appears to be comfortably centered on the social fault-lines of modern Japan. She has a dystopian novel about (The Birth Murder) that attempts to solve the low birthrate in Japan by allowing people to kill one person for every 10 children they produce (with the aid of artificial uteruses).

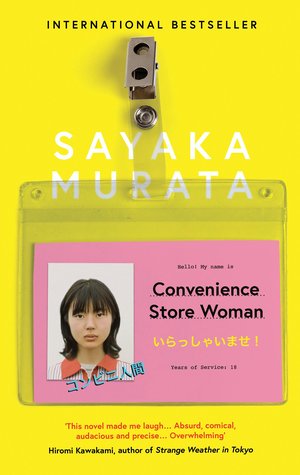

Convenience Store Woman won Japan’s most prestigious literary award in 2016 – the Akutagawa Prize. I hope this recognition leads to more of her work getting translated into English. I thought this book was magnificent, and am looking forward to reading more from her.