The children have a game: keep their parental status secret. If they keep it secret from each other, they can keep it secret from themselves. They won’t have to be the “children of” anyone. They don’t have to claim allegiance with the drunks in the Great House who let the world burn. Their game, and much of this book in general, brought to mind strong memories of “Old College Try” by The Mountain Goats.

The children have a game: keep their parental status secret. If they keep it secret from each other, they can keep it secret from themselves. They won’t have to be the “children of” anyone. They don’t have to claim allegiance with the drunks in the Great House who let the world burn. Their game, and much of this book in general, brought to mind strong memories of “Old College Try” by The Mountain Goats.

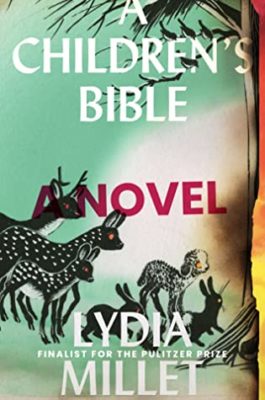

A Children’s Bible is more than what it seems. It’s presented as an account of a fateful and fraught summer, documented by teenage Evie, but it also is-well- the bible of the children. The children here, a ragtag collection of kids ranging from kindergarten age through late teens, are left to their own devices while their parents attempt to relive college glory days for the summer. They keep separate from the parents. They refuse to acknowledge their presence, and they refuse to take ownership of them as well. They are independent and free. This is not a Lord of the Flies situation; the children are committed, organized, and invested in the survival and care of each other. They are children of privilege, but they are unwilling to partake in idle oblivion like their parents.

“We figured there were probably a couple of charity cases, or at least a sliding scale. David, a techie who dearly missed his advanced computer setup back home, had let slip that his parents rented. Received a demerit for that. Not for the lack of home ownership—we hated money snobs—but for getting soft and confessional over a purloined bottle of Jäger. Drink their liquor? Sure, yes, and by all means. Act like they acted when they drank it? Receive a demerit. For it was under the influence, when parents got sloppy, that they shed their protective shells. Without which they were slugs. They left a trail of slime.”

The relationship between the parents and the children is toxic. The relationship between the parents and each other is toxic. The relationship between the parents and the world is, of course, toxic. What begins as an insufferable vacation quickly builds steam before escalating into the (beginning of) the end of the world.

“That time in my personal life, I was coming to grips with the end of the world. The familiar world, anyway. Many of us were. Scientists said it was ending now, philosophers said it had always been ending. Historians said there’d been dark ages before. It all came out in the wash, because eventually, if you were patient, enlightenment arrived and then a wide array of Apple devices. Politicians claimed everything would be fine. Adjustments were being made. Much as our human ingenuity had got us into this fine mess, so would it neatly get us out. Maybe more cars would switch to electric. That was how we could tell it was serious. Because they were obviously lying.”

The children have each other, the land around them, and few guides. Some guides take the form of adults who have not previously failed them. Some guides are literal written records. One of the mothers notices that Jack, Evie’s little brother, likes to read. He reads children’s picture books, but she tells him that he is missing something. She gifts him the titular children’s bible. Jack is the heart of the story, and he is brought to achingly beautiful life in the audio performance by Xe Sands. “Your storybook’s not a user’s manual”, says one of the older kids to Jack when he references the bible throughout their adventure. Jack, ever the humanist and ever the scientist, has another idea. He has a mystery to solve, and his mystery may keep them all afloat.