CBR12 BINGO: I Wish

CBR12 BINGO: I Wish

Double BINGO!

Vertical: The Roaring 20s, Pandemic, Friendship, Green, I Wish

Horizontal: Money, No Money, Repeat, I Wish, Violet

The title of my review comes from the classic episode of The Office in which we learn about the Finer Things Club.

Oscar: Can you imagine a life where all you have to do is summer in the Italian countryside?

Pam: And spend time with George Emerson. That’s what I would do.

That sums up why I selected A Room with a View as my entry for the I Wish square.

Comedy aside, Pam makes some relevant points about the novel before Andy attempts to insert himself into the exclusive club’s discussion: Forster uses Italy to represent passion, and Lucy is torn between passion and convention.

The novel opens with Lucy Honeychurch and her “spinster” cousin Miss Charlotte Bartlett vacationing in Florence. In spite of being in one of the most beautiful and romantic cities in the world, Charlotte is complaining nonstop because they were promised a room with a view of the Arno, and instead they have been given a room with a view of the depressingly unimpressive courtyard. On top of that, their hosts are not real Italians at all, but cockney! If Charlotte and Lucy had wanted to slum it with East Londoners, they’d have stayed in England, for heaven’s sake. Now, I admit that disappointing accommodations can be annoying when you are on a trip, but listening to Charlotte complain is worse than looking out over a stinky courtyard, especially when Italy is a step outside your door. Charlotte will prove herself to be the most annoying character in the novel, constantly complaining and butting into Lucy’s business (she is Lucy’s chaperone, a charge she takes very seriously), and generally putting on a martyr mantle because she is poor and Lucy’s mother is paying part of her way on this trip. The woman is so joyless, if she lived in the 20th century, she’d no doubt be staying in her room listening to the Smiths when Lucy wants to go out and see Florence (as it is, Charlotte prefers to spend her first day “settling in”).

In an attempt to be helpful, another guest in their hotel offers to swap his and his son’s rooms with Lucy and Charlotte, since they have a view and “men don’t care about having a view.” Charlotte about has a fainting fit at this outrageous and inappropriate suggestion. How dare Mr. Emerson and his son George attempt to put Lucy under an “obligation” to them.

Edwardians, man.

Gift horse, meet mouth

Charlotte and Lucy are ready to flounce out of the hotel altogether when Mr. Beebe, a reverend they know from England, arrives. Now the place seems more respectable, so they stay. In addition, Mr. Beebe convinces Charlotte that the Emersons are harmless and that nothing improper will come of swapping rooms with them. Reluctantly, Charlotte agrees, though she insists on taking the larger room that belonged to the son, George, because Lucy’s mother wouldn’t like it if Lucy stayed in a room that was formerly occupied by a young man. Apparently Charlotte is unfamiliar with how hotels work.

Fortunately for all concerned, black lights had not been invented yet.

The plot heats up when Lucy, wandering around Florence by herself, witnesses a fight between two Italian men that ends with one stabbing the other. George, who is nearby and witness the same event, catches Lucy in a faint. They share a moment. Could that be sexual tension we feel?

Somebody throw some cold water on these two.

Things really come to a head, though, during an outing with several of the other hotel guests. Wandering off on her own, Lucy comes upon a beautiful field of violets. Guess who is also appreciating the beauty of nature at that particular moment? George, Mr. Passion himself! Overcome with emotion, he kisses Lucy! She is shocked, but. . kinda, maybe enjoyed it? Unfortunately busybody Charlotte arrives and witnesses the event. Later, at the hotel, they decide to take off early for Rome, thus avoiding any more drama with the Emersons.

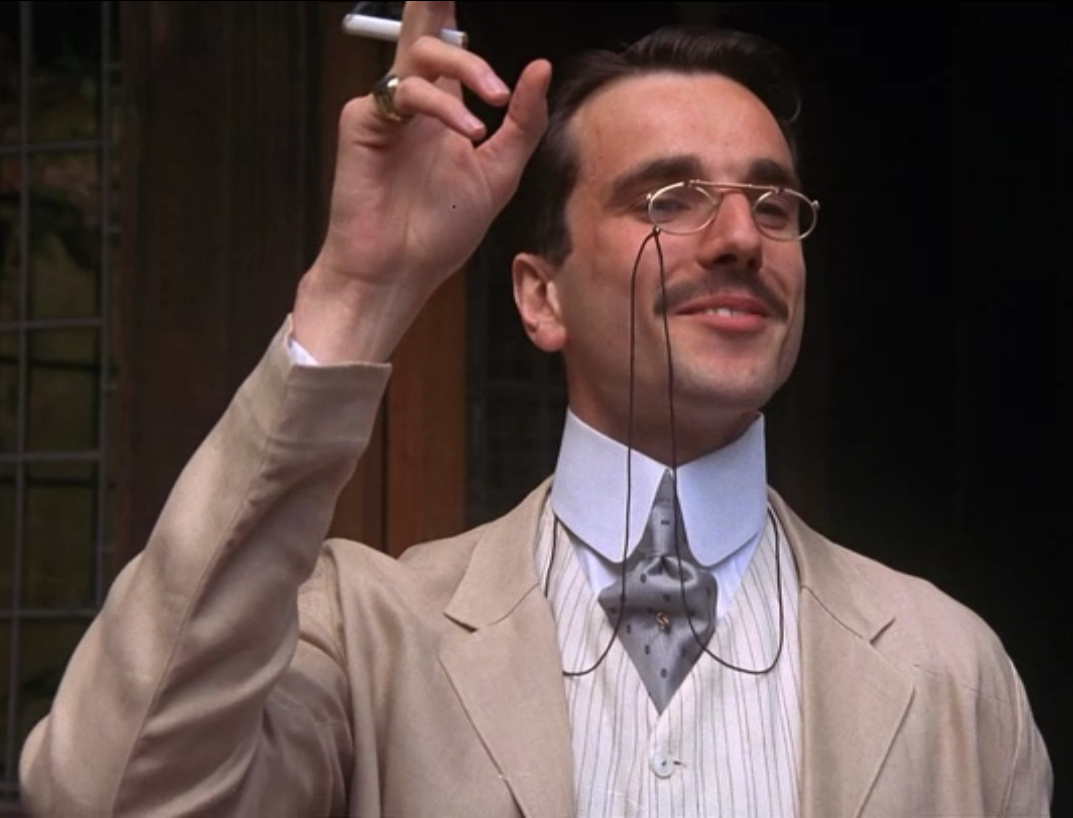

Part II of the novel begins with Lucy becoming engaged to Cecil Vyse, whom Lucy and Charlotte met up with in Rome. For the rest of the novel, pretty much everyone except Cecil wonders why in the world Lucy accepted his proposal. He’s got money, sure, but he’s enormously dull and a prig to boot. Of Lucy, he remembers “That day she seemed a typical tourist–shrill, crude, and gaunt with travel. But Italy worked some marvel in her. It gave her light, and–which he held more precious–it gave her shadow. Soon he detected in her a wonderful reticence. She was like a woman of Leonardo da Vinci’s, whom we love not so much for herself as for the things that she will not tell us.” Ugh! The other characters in the novel put up with Cecil, but nobody particularly likes him much: not Lucy’s brother Freddy, not Mrs. Honeychurch, and not kind Mr. Beebe.

Say what you want, the guy sports killer pince-nez

The remainder of the novel illustrates Lucy’s struggles between the life that’s expected of her and her desires. Throughout the novel, Lucy questions why a woman is expected to behave in certain ways. “Charlotte had once explained to her why. It was not that ladies were inferior to men; it was that they were different. Their mission was to inspire others to achievement rather than to achieve themselves. Indirectly, by means of tact and spotless name, a lady could accomplish much. But if she rushed into the fray herself she would be first censured, then despised, and finally ignored. Poems had been written to illustrate this point.”

The contrast between Lucy and Charlotte is highlighted from the earliest pages. When Lucy “reached her own room she opened the window and breathed the clean night air,” whereas Charlotte “fastened the window shutters and locked the door, and then made a tour of the apartment.” The Emersons fly in the face of convention by acting on how they feel. As George pursues Lucy in a way that is deemed inappropriate, so his father also pursues people’s friendship in unexpected and unsettling ways. As George says, “He is kind to people because he loves them; and they find him out, and are offended, or frightened.”

Other minor characters represent other aspects of Edwardian society. Would-be novelist Miss Lavish represents intellect (or, I would say, “pseudo-intellect”). The Alans sisters represent breeding. Freddy represents youth. It’s worth noting that Freddy is the one minor character who sorta digs the Emersons. It seems that he is still so young and playful that he hasn’t grown into society enough to know he’s supposed to frown on the unconventional.

A Room with a View is one of the most delightful novels of the Edwardian era, touching on themes of tradition, society, class, feminism, and individualism. It does so with humor and passion. This is one of the most relatable novels the early 20th century has to offer. If you are interested in reading a “classic” and don’t know where to start, I highly recommend.

It gets the Finer Things Club stamp of approval.