CBR12 BINGO: Repeat

CBR12 BINGO: Repeat

This is a repeat of the Book Club category, as my social distancing book club meets again in September.

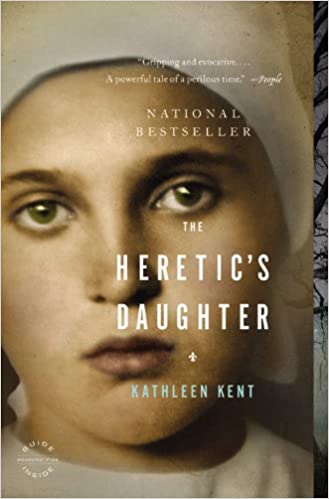

For this meeting of my book club, we decided to go a little heavier and read this historical fiction about the Salem witch trials. Author Kathleen Kent has a vested interest in the topic, as she is a tenth-generation descendant of Martha Carrier, one of the first women accused and tried as a witch in Salem in 1692. The Heretic’s Daughter looks a the hysteria of the trials and horrifying conditions in which the prisoners were kept through the eyes of Sarah Carrier, Martha’s elder daughter.

While men were also accused and hanged (and one, who refused to speak to the court, pressed to death), the majority of the “witches” were women, and the novel nods to feminism, particularly in the description of Martha after she is named: “She was too singular, too outspoken, too defiant against her judges, in defense of her innocence, and it was for this, more than for proof of witchcraft, that she was being punished.” History has always tried to punish strong women as rebellious.

Martha Carrier, 17th century “nasty woman”

Martha Carrier, 17th century “nasty woman”

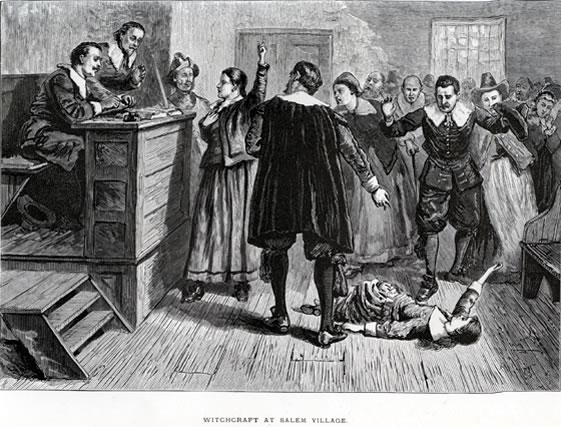

As a long-time admirer of Arthur Miller’s The Crucible, I’m always intrigued by this subject and enjoyed reading more deeply about the trials and the individuals who were accused. Whereas Miller focused on the madness of condemning people on the word of those who have much to gain by the accusations and the parallels with McCarthyism, Kent focuses on the relationships between the victims. Sarah and her mother have a tense relationship, one that Sarah only fully comes to understand and appreciate when her mother is taken from her. In prison (for all of Martha’s children were also arrested), Sarah and her brother Tom expose their feelings for each other in way that would have made them too vulnerable pre-arrest. In the torment of prison, they have nothing to cling to except each other.

The horrors of the prison conditions are exposed in a way I hadn’t read before. “The smell of rot was so sharp and so far-reaching that my eyes ran over and the furthest recesses of my nose and throat felt a if they had caught fire. But it was not just the rot of human waste that was so powerful, it was the sweetly sour rot of badly turned food and perhaps something still living that was only partially dead: musty and coppery and bog-laden.” That the families of the accused had to pay the sheriff for their manacles; that the sheriff’s wife would trade small amounts of extra food for prisoners’ good-quality clothing in a ploy to line her own pockets; that those who were ultimately declared innocent still had to pay their way out of prison; that, in 1711, when the Massachusetts Bay Colony reversed the sentences of the wrongly accused, Martha Carrier’s husband received seven pounds English money in recompense; all this demonstrates how warped and hopeless was the situation that these families faced. There will never properly be a way to honor the people that suffered under this madness.

I give high praise to the second half of this novel. The problem is, the first half is so slow-moving and non-witch related that I suspect some readers may call it quits before it really gets moving. Kent clearly wants to tell the story of her ancestors, including their move to a new village and the infestation of small pox that eventually claims Martha’s mother’s life. This is good background, but shouldn’t take up the first 160 pages of a 330-page book. The writing is lovely, but dense. Overall, I’d give 4 stars to the second half of the book, but only 3 stars to the first half. If you can push through, you will be satisfied. Martha Carrier and the other 19 people murdered by the courts deserve our attention.

Martha Carrier, wrongly accused: Nevertheless, she persisted.