An elderly professor gives lectures on Greek history on a cruise ship, a Polish family vacations in Croatia with dramatic consequences, an immigrant tries to build a new life on a remote island in the north. In the 17th century, Filip Verheyen discovers the Achilles tendon, and Frederik Ruysch revolutionizes embalming techniques, while today, plastination makes it possible to preserve bodies in an incredibly detailed and lifelike fashion.

An elderly professor gives lectures on Greek history on a cruise ship, a Polish family vacations in Croatia with dramatic consequences, an immigrant tries to build a new life on a remote island in the north. In the 17th century, Filip Verheyen discovers the Achilles tendon, and Frederik Ruysch revolutionizes embalming techniques, while today, plastination makes it possible to preserve bodies in an incredibly detailed and lifelike fashion.

These are just some of the stories told in this book, and in between, there are musings and vignettes on almost everything related to travel, from airports to travel psychology, trains, the Paris syndrome, the clientele of hostels, or guide books. The book is made up of 116 short pieces, some of them only a few lines long, others dozens of pages. Although this leads to a high level of fragmentation, not only did the book manage to hold my interest throughout, I would even say that this is a big part of its charm and could be meant to imitate the stops and starts but also the meandering of a long journey, as beginnings and endings also play a significant part in the book, as well as the transience and instability of our world. In general, the focus is not only on travel in the sense of being in motion between locations, but also on being in a place that is not one’s home. While the touristic aspect of this is only glanced at, the reasons of the characters are varied and range from work-related to personal, or, in extreme cases, may even be an attempt to find a new home that would allow them to be reborn into a different life, which would ultimately end the journey.

Then there are the parts of the book that are concerned with the body, the vessel that keeps us in motion, but is also our constant. When endless travelling makes people forget where they are, their body is still there and as familiar as any home can be. When the mind leaves the body in death, the body stays behind and can be preserved through embalming or plastination. Frederik Ruysch sells his collection of embalmed bodies and body parts to Peter the Great, and all of the specimens have to be packed up and are shipped to Russia on a last journey. Filip Verheyen, on the other hand, loses a leg as a young man and keeps this same leg, preserved in a jar, close until his death, but the trajectory of his life is inescapably altered by the loss of his limb. This emphasis on the physical is a startling aspect of the book because a journey is often linked to a state of mind or even imbued with some spiritual meaning while the body is only a means to the end, but here the act of moving is brought back down to earth.

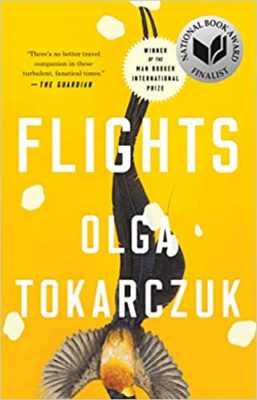

But what is the author trying to tell readers about modern-day travelling and the body that makes it possible? This is such an innovative and unpredictable book that this question is impossible to answer. I have laid out some of my own interpretation here, but I believe that every reader will have their own take on matters. Olga Tokarczuk leaves the door wide open for all kinds of thoughts and explanations, and she invites her audience to venture forth and travel through it.

CBR12 Bingo: Yellow