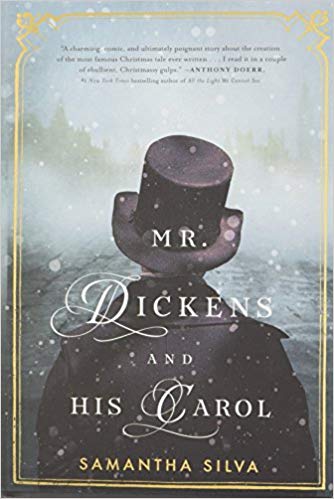

Almost every year I’ll take a time-out from holiday mayhem and revisit A Christmas Carol. I was reluctant to review it for CBR, though, because I did that already, back in 2014. So I hit the internet and searched for something Christmas-related that I hadn’t read before and found Mr. Dickens and His Carol on several lists of best Christmas books.

Almost every year I’ll take a time-out from holiday mayhem and revisit A Christmas Carol. I was reluctant to review it for CBR, though, because I did that already, back in 2014. So I hit the internet and searched for something Christmas-related that I hadn’t read before and found Mr. Dickens and His Carol on several lists of best Christmas books.

Mr. Dickens and His Carol is a fictional account of how Dickens came to write that famous Christmas ghost story. A few details do come from real life, such as Dickens being influenced by his father going to debtor’s prison when Charles was a young boy, the disappointing sales of Martin Chuzzlewit, and the writing of A Christmas Carol out of financial necessity. In this world, though, Dickens’ publishers essentially blackmail him into writing a Christmas book that he doesn’t want to write. His wife, fed up with his grumpiness, takes the kids and goes to Scotland for Christmas, leaving Dickens to brood and wander the streets of London, where he meets a mysterious woman named Eleanor Lovejoy. Inspired by Eleanor, he gets his mojo back, writes his novel in time to meet the holiday deadline, and eventually remembers the true meaning of Christmas (which is not, in fact, to cheat on your wife while she is away in Scotland).

Samantha Silva freely admits in the Author’s note that the novel is a “playful reimagining” of how the story came to be, and apologizes to “Dickens aficionados and scholars who might bristle at the liberties I’ve taken.” Sadly for me, the Autor’s note came at the back of the book so I didn’t have a chance to heed this warning.

I’m not opposed to fictionalized accounts and playful reimagining (though it’s true that the more one cares about a topic, the less tolerant one becomes to inaccuracies). I just didn’t find the story compelling. The publisher’s description of the novel references “clever winks to [Dickens’] works.” Not to be mean-spirited, but a character handing Dickens a business card with the name Fezziwig on it doesn’t strike me as particularly sly. This novel reads a bit like Shakespeare in Love without the brilliance of Tom Stoppard’s writing. Plus, [spoiler] it includes a dash of the Sixth Sense, not to mention a final scene reminiscent of It’s a Wonderful Life. Did I mention the story also includes a fictional urchin named Tim(othy)? Didn’t see that coming, did you?

So after being disappointed by this novel, I turned back to the original Dickens classic, and my heart was happy again. No matter how many times I read A Christmas Carol, it soothes my soul, from the first mention of Marley being dead as a door-nail (and subsequent irrelevant musings about ironmongery) to Scrooge’s drunken giddiness at finding himself alive. It would be hard to name another redemption arc in literature as perfect and poignant as that of Ebenezer Scrooge as brought to life by Dickens’ pen. From his characteristic parsimony (“Darkness was cheap, and Scrooge liked it), to his callous disinterest in the poor (” ‘And the Union workhouses?’ demanded Scrooge. ‘Are they still in operation?’ “) to his final conversion (He became as good a friend, as good a master, and as good a man, as the good old city knew”), just about every one of the fewer than 30,000 words in this story is perfect. The story remains as relevant today as it was in 1843, as evidenced by what I consider to be the most underrated quote in the Dickensphere:

“There are some upon this earth of yours,” returned the Spirit, “who lay claim to know us, and who do their deeds of passion, pride, ill-will, hatred, envy, bigotry, and selfishness in our name, who are as strange to us, and all our kith and kin, as if they had never lived. Remember that, and charge their doings on themselves, not us.”

In short, you may enjoy Mr. Dickens and His Carol as a light bit of holiday fluff, but nothing can compare to the amazing Mr. Dickens himself.