I was 16 when I read The Handmaid’s Tale and I was just beginning my love affair with dystopian tales. I don’t think I liked bleak stories all that much growing up, but man, as soon as I read Fahrenheit 451 they were all I wanted. Give me some of that sweet, sweet harrowing future straight to the veins, and anything like it.

I was 16 when I read The Handmaid’s Tale and I was just beginning my love affair with dystopian tales. I don’t think I liked bleak stories all that much growing up, but man, as soon as I read Fahrenheit 451 they were all I wanted. Give me some of that sweet, sweet harrowing future straight to the veins, and anything like it.

When a friend gifted me The Handmaid’s Tale, I thought I’d love it. I read it voraciously, in about two days, and then, enraged, threw it against a wall. If you know the end of that book, you know why it would be frustrating, especially for a teenager. The ending wasn’t the only thing that angered me though, as I think I was angry about the content in all the ways it was presented. I wasn’t just mad at the society of Gilead, or at Offred and her actions, I was mad at Atwood for her writing style, for her prose, for her distinct feminine voice. To explain, it was 2002, and it was really, really uncool to be anything resembling a feminist, and I was a girl who resented feminine ways of writing and viewing the world. I had some seriously internalized misogynistic notions that took me a long time to overcome. I think I greeted the book with a certain disbelief that the world could be cruel to women in the way Atwood describes- despite her assertion that everything she wrote is something that has already happened, in some way or another, throughout history. I was mad at Atwood for synthesizing a world so ruthless in its cruelty, and frustratingly plausible.

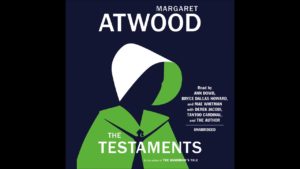

I was hesitant to read The Testaments, not just because of my own history with the author, but because the Handmaid’s Tale television program has become increasingly derivative of the world building and the source material, treating June like a plot-armoured Wonder Woman. So, I compromised with myself, and picked up the audiobook through a subscription credit. The Testaments follows three narrators: an Aunt inside Gilead, a young girl destined for wife-hood inside Gilead, and a young woman watching from afar in Canada. It contains their descriptions of their lives and that’s about all you should know going in.

The voice acting is superb. Aunt Lydia, voiced by Ann Dowd, brings her trademark voice and skill from the television show, and is joined by Bryce Dallas Howard and Mae Whitman. I found Whitman a bit frustrating to listen to at times, and had to remind myself that she was voicing a 16 year old. Her character is the most frustratingly written out of all of them, but teenagers often are, both in imagined narratives and real life.

The book provides some satisfying closure and ties up a lot of loose ends from The Handmaid’s Tale, and avoids the more unbelievable elements the TV show is known for diving into. What I found sad to miss was the prose filled internal monologue and dream-like remembrances we were given in The Handmaid’s Tale. I miss the femininity of Atwood’s earlier writing style, here replaced by a utilitarian spoken voice element that is all fact and very little fantasy. I wish she’d been able to incorporate that into this book because I think that, in this time, we can afford to be blatantly feminine in our writing and maybe should be, in the face of Incels, Trumps, and rising misogynistic powers. I wish she’d done that so young people who are adverse to that writing would confront their own misogyny, as I did in my youth, and eventually examine why they cringe at it. I’ve had a long, complicated history with Atwood’s books, but I’m grateful for what she writes and how she does it; she’s forced me to examine how I feel towards myself and my place in the world in ways I wouldn’t have done without her.