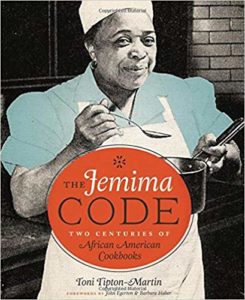

It’s one thing to know intellectually that a system of oppression requires erasure of the oppressed, and another thing to try to understand how that erasure happens and glimpse the truth being hidden. When I read Michael Twitty’s The Cooking Gene, he referenced Toni Tipton-Martin’s The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. It immediately went on my tbr. A few weeks ago I was browsing around on NetGalley and saw it there, though it was published in 2015. I snapped it up and have been reading it off and on for the last 5 weeks. This is an honest review.

It’s one thing to know intellectually that a system of oppression requires erasure of the oppressed, and another thing to try to understand how that erasure happens and glimpse the truth being hidden. When I read Michael Twitty’s The Cooking Gene, he referenced Toni Tipton-Martin’s The Jemima Code: Two Centuries of African American Cookbooks. It immediately went on my tbr. A few weeks ago I was browsing around on NetGalley and saw it there, though it was published in 2015. I snapped it up and have been reading it off and on for the last 5 weeks. This is an honest review.

Tipton-Martin is an award winning author, a culinary journalist who has written for the LA Times and was the Food Editor for the Cleveland Plain Dealer, and a community activist. While working at the LA Times, she began to wonder where the black cooks were in the history of American foodways. She began collecting the evidence of African American cooks and butlers – cookbooks from the 1800’s to the present, many of which were self published. The cookbooks provide a record of knowledge and skill, defying the stereotypes and illuminating the connections Black cooks maintained despite systemic oppression.

In her introduction, Tipton-Martin talks about the importance of the record these cookbooks and household management book provide in the face of Aunt Jemima.

Historically, the Jemima code was an arrangement of words and images synchronized to classify the character and life’s work of our nation’s black cooks as insignificant. The encoded message assumes that black chefs, cooks, and cookbook authors – by virtue of their race and gender – are simply born with good kitchen instincts; diminishes knowledge, skills, and abilities involved in their work, and portrays them as passive and ignorant laborers incapable of creative culinary artistry.

Throughout the twentieth century, the Aunt Jemima advertising trademark and the mythical mammy figure in southern literature provided a shorthand translation for a subtle message that went something like this: “If slaves can cook, you can too,” or “Buy this flour and you’ll cook with the same black magic that Jemima put into her pancakes.” In short: a sham.

Take Craig Claiborne, from Sunflower, Mississippi, for instance. In 1987, the the former New York Times food editor organized three hundred recipes from “many of the South’s best cooks,” including Paul Prudhomme and Bill Neal. Only one of them, Edna Lewis, was black. … But he blushes at never having heard of catfish in white sauce “until we experimented with it in my own kitchen, calling it, ‘an excellent Southern dish with French overtones.’” The free woman of color Malinda Russell called the dish Catfish Fricassee in her groundbreaking cookbook way back in 1866.