CBR11bingo: Award Winner – Nebula Award for Best Novel (1974), Hugo Award for Best Novel (1975), Locus Award for Best Novel (1975)

CBR11bingo: Award Winner – Nebula Award for Best Novel (1974), Hugo Award for Best Novel (1975), Locus Award for Best Novel (1975)

Double Bingo!

Horizontal: I Love This, Not My Wheelhouse, Listicle, Rainbow Flag, Award Winner

Vertical: Reading the TBR, Science!, History/Schmistory, Award Winner, Summer Read

Last year I read my first Le Guin Novel, The Left Hand of Darkness, and couldn’t stop raving about it. On the advice of a fellow Cannonballer, I decided to read The Dispossessed for my Award Winner Square (tip for next year’s Bingo, Le Guin also works for “Birthday” assuming bingo spans October again).

The plot of The Dispossessed is a little complicated, so bear with me. There are two planets, Urras and Anarres (the people of Urras consider Anarres their moon, and vice versa). Urras is highly developed and capitalistic, the kind of place that would be the focus of an intergalactic edition of Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous.

Like this, but with aliens. So. . . like this.

Anarres is an offshoot of Urras originally initiated by an anarchist named Odo, where the concept of ownership is nonexistent. Nevertheless, Anarres has resources that Urras needs and, fearing that Urras will attack them if they don’t play ball, the Anarresti hold their noses and establish a trade agreement in which freighters from Urras are permitted to come in and out of a single port that’s enclosed by a (mostly symbolic) wall several times per year.

As the story begins, a physicist named Shevek has decided to take the freighter back to Urras, a move that is so unconventional that some of his fellow Anarresti have even come to the port to protest and throw rocks at him for betraying his planet. On Urras, Shevek is treated like a celebrity and shown all the best that the planet has to offer. From the beginning, Shevek notices some disturbing trends about his hosts. For one thing, Urras is blatantly sexist. Before he even gets off the ship, he gets into a debate with a doctor about equality that absolutely stupefies his new acquaintance, “You can’t pretend, surely in your work that women are your equals? In physics, in mathematics, in the intellect? You can’t pretend to lower yourself constantly to their level?” Later, on Urras, he questions a fellow scientist about why there aren’t women in the scientific fields and is told, “Can’t do the math; no head for abstract thought; don’t belong.”

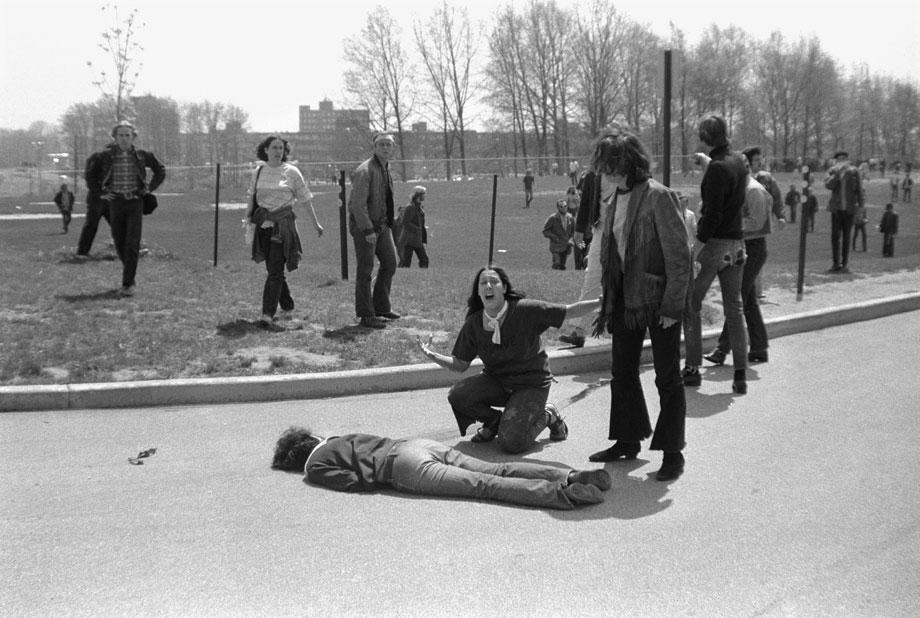

Shevek, it turns out, has come to Urras to work on his General Temporal Theory, which he believes is going to benefit the entire world. Not having any concept of ownership on Anarres, he’s slow to realize that authoritarian men on Urras see his work as a key to power, to controlling other governments and peoples (unlike Anarres, Urras is home to multiple “countries”). Once he realizes that his hosts are going to use his theories for evil, he seeks out an underground population of anarchists and agrees to join their upcoming protest, which ends with the protesters being shot at by their own government.

Not-so-speculative fiction

So Le Guin is clearly anti-capitalist, pro-anarchist, right? Well. . . it turns out Anarres isn’t perfect either, and not just because of droughts and people starving. The novel is told through flashbacks, with each chapter alternating between Shevek’s time on Urras and his early life and the years leading up to his departure. The reason he goes to Urras in the first place is because he can’t get his ideas published on Anarres. While there is technically no power structure, there is always a way to control individuals, and Shevek has been prevented from advancing his potentially life-altering theories by a petty, possessive individual named Sabul. In a flashback chapter, Shevek and a close friend get into a heated discussion on the topic of freedom and control, with the friend citing Sabul’s “power” as a prime example. “You can’t crush ideas by suppressing them. You can only crush them by ignoring them. By refusing to think, refusing to change. And that’s precisely what our society is doing! Sabul uses you where he can, and where he can’t he prevents you from publishing, from teaching, even from working. In other words, he has power over you. Where does he get it from? Not from vested authority, there isn’t any. Not from intellectual excellence, he hasn’t any. He gets it from the innate cowardice of the average human mind. Public opinion! That’s the power structure he’s part of, and knows how to use. The unadmitted, inadmissible government that rules the Odonian society by stifling the individual mind.”

One of the reasons I love Le Guin’s novels is because I have to work at them. She doesn’t have easy answers and doesn’t pretend to have them. She volleys ideas at you and you can either catch them, or swat them away, or let them roll around on the floor in front of you. Maybe they roll under the couch and you find them again while cleaning and pick them up and consider them again.

Le Guin’s ideas are a lot like cat toys in this scenario

The point is, she makes me think, which is what brilliant sci fi is supposed to do.