Catherine’s War is a Holocaust story with a twist. This time a young, French-Jewish girl, Rachel, goes into hiding but does it in the open. She (and other children) do not stay in any one place too long (usually not by choice). They sometimes are only one step ahead of the Nazis at any point.

Catherine’s War is a Holocaust story with a twist. This time a young, French-Jewish girl, Rachel, goes into hiding but does it in the open. She (and other children) do not stay in any one place too long (usually not by choice). They sometimes are only one step ahead of the Nazis at any point.

Julia Billet created (and Ivanka Hahnenberger translated), Rachel, our narrator. Rachel goes to the progressive Sèvres Children’s Home where children of both faiths learn in a non-traditional setting. We see the children (bravely but somewhat naively) wanting to fight the Nazi’s and teachers doing their best to protect the students, but of course, the Jewish students (and teachers) mostly. This is done in seemingly small ways: not having the Jewish students wear the yellow star, not learning the new anthem (but finding creative ways of covering themselves when needed), having the Jewish students change their names (Rachel becomes Catherine) and simply teaching the children about independence and freedom. But they are far from small gestures.

I could go on and tell the whole story. But a few highlights: the main being how Rachel (with the camera given to her by a beloved teacher) journals the war. It is done through the people that helped her and the other children and the places that offered shelter (physically and spiritually). She learns to love not only the camera and what it creates, but others and herself through her journey. And finally, when she sees her old apartment and the streets of Pairs when liberation finally comes, the camera and she see more than ever imagined. There are details to the story that seem small, but like the gestures of the teachers large: the school is in the occupied part of France, the first place Rachel finds to develop the cameras film, who she meets there and so on. Each piece of the story creates the larger picture of the time and events.

There are a few plot points that can seem a bit romantic (Rachel falls in love quickly; a photographer she meets, despite a physical deformity, is not targeted by the Nazis; her understanding of situations seems a bit mature for her age yet, she can be oddly naive; even when they are found by the Nazis things usually work out). It is not graphic, but areas are not shied away from (a scene at the end shows what happened to French women who collaborated with the Nazis and earlier, we see a friend of hers has lost an arm). Yet, over all it is a pleasant read, which, I realize is an odd thing to say about a Holocaust story.

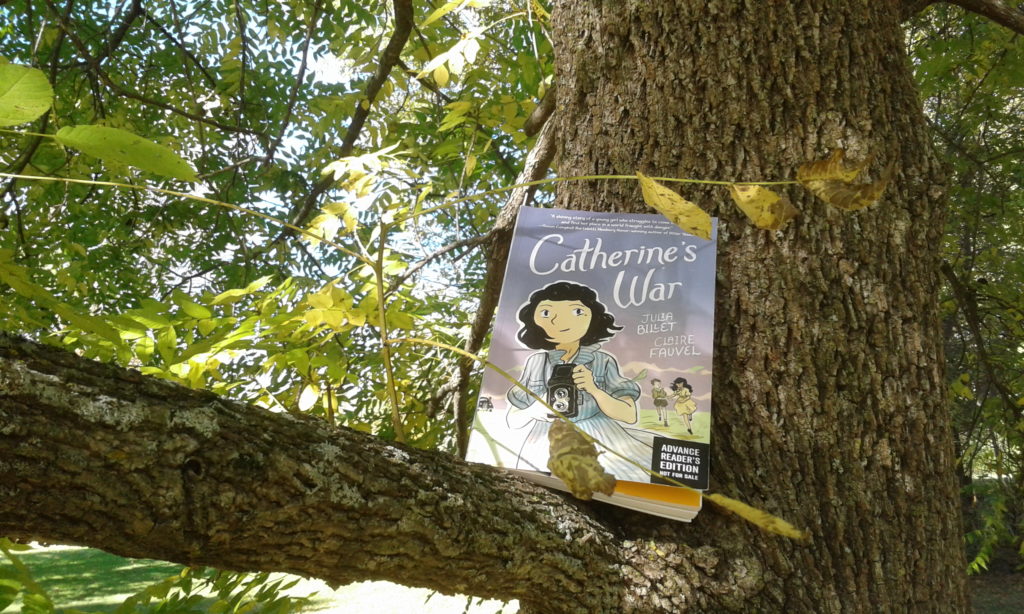

This is partly due to Claire Fauvel’s illustrations. They are happy illustrations. There is not a lot of the ugly of war. It is there but done in a sensitive manner. Things move quickly, text wise, but the illustrations help show the changing time.

Overall, this is a good addition to the many books on the subject and another graphic novel to add to your collection.