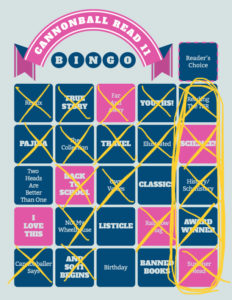

Cbr11bingo Award Winner, bingo #7

Cbr11bingo Award Winner, bingo #7

Edith Wharton was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize for literature with The Age of Innocence in 1921.

I’ve decided that Edith Wharton is one of my favorite authors, right up there with Toni Morrison and Jane Austen. In past CBRs, I’ve reviewed The House of Mirth and Ethan Frome and marveled at her artistry with words and her dissection of the American class system, particularly New York society, at the turn of the 20th century. Her novels involve individuals who attempt to fly in the face of convention and grapple with thwarted dreams, revealing the seamy underside of elite society. In The Age of Innocence, Wharton delivers another punch to the gut, exposing the power and hypocrisy of a small group of families who act as arbiters of proper behavior and ruthlessly police their own ranks.

The Age of Innocence is set in 1870s New York among society’s upper crust. Newland Archer, the focus of the story, is a man of good family about to become engaged to May Welland, a beautiful young woman from another respected family. The Archers and Wellands run in the circle of elite families in “moneyed” New York. The story opens with Newland on his way to the opera. Everyone of his circle is there and we are privy to Newland’s thoughts as he arrives and mentally evaluates his peers and his place among them.

Singly they betrayed their inferiority; but grouped together they represented ‘New York’, and the habit of masculine solidarity made him accept their doctrine in all the issues called moral.

While Newland considers himself intelligent and an independent thinker, superior to his peers, he is also a conformist. He would not dream of acting outside conventional norms.

…what was or was not ‘the thing’ played a part as important in Newland Archer’s New York as the inscrutable totem terrors that had ruled the destinies of his forefathers thousands of years ago.

Among the men in his circle, two stand out as the standard bearers for what is correct. Lewis Lefferts is “the foremost authority on form”, while an older gentleman named Sillerton Jackson is the authority on family pedigree and history, i.e., scandals. These men are all present at the opera when a stir occurs centered on the opera box where May Welland and her family — the Manson Mingott clan — are seated. May’s cousin, Countess Ellen Olenska, has arrived. Lefferts and Jackson are scandalized, as Ellen Olenska has separated from her Polish husband and left him behind in Europe. While one might forgive the family for accepting one of their own in their private homes, for the Mingott/Welland family to publicly acknowledge Ellen in this way is bad form, an offense against “taste”. Given Newland’s impending engagement to May, this very public faux pas could have negative reverberations for him and his family as well. He is initially angry but his devotion to May and his sense of her own discomfort over the situation spur him toward an act of chivalry. Newland makes a point of getting to May’s box immediately to show his solidarity with her family, and he asks that they announce their engagement that very night at the ball following the opera.

Rumor’s about Ellen’s background circulate quickly with more than a whiff of scandal attached to her circumstances. “Good society” shuns her until the Archers plead with the leading family of New York society to demonstrate public acceptance of her. But when Ellen indicates that she wishes to pursue a divorce, not only does the law firm representing her (a firm for which Newland works) try to dissuade her from this course, but her own family does as well. Divorce simply isn’t done no matter how terrible the circumstances. “Poor Ellen” is generally pitied but only Newland and the matriarch of the Mingott clan — Mrs. Manson Mingott — seem to appreciate the unfairness with which Ellen is treated.

Meanwhile, Newland is pressuring May and the Wellands to have the wedding sooner as opposed to later, which is not the normal way of approaching engagements and nuptials. At he same time, Newland is beginning to see both May and Ellen in a new light, complicating his personal situation as well as his public image. Newland prides himself on his powers of perception, often believing that he knows what others are thinking, but he is blind to the way he comes across to his circle. His perception of himself as above the fray, independent, and a step ahead of the rest will be shaken to the core by the end of the novel.

I love Edith Wharton’s novels for their brutally honest portrayal of upper class behavior and the plight of women. Wharton was herself born into “moneyed New York” and so she wrote about what she knew. Wharton married and later divorced, moving to France to write. She is able to describe with precision and an unflinching eye the manner in which family members sacrifice one member for the good of the collective, as well as about the hypocrisy of men judging a woman fleeing an abusive marriage while they themselves are engaged extra-marital affairs. These arbiters of “taste” and “form” found subtle but devastatingly effective ways to bully and threaten those who challenged their rules. And it wasn’t just the men who acted as enforcers. Women of this class had a vested interest in preserving their own positions, so the idea of female solidarity in the face of unfair treatment was unknown. I remember thinking it strange that Martin Scorcese wanted to bring this novel to the screen (1993), but it seems that The Age of Innocence is not so far removed from his other films. It’s a great novel, an American classic, in my opinion.