CBR11bingo: Not My Wheelhouse

CBR11bingo: Not My Wheelhouse

BINGO, diagonally: Cannonballer Says, Not My Wheelhouse, Own Voices, Illustrated, Reading the TBR

I may have been called a tree hugger in my day, but botany has never been my area. I can enjoy plants from a purely aesthetic point of view, but reading an entire book dedicated to trees? For my tree fix, I’d prefer to turn to Joyce Kilmer’s 12-line poem and call it a day. But Jonathan Drori’s Around the World in 80 Trees. . . I’m speechless!

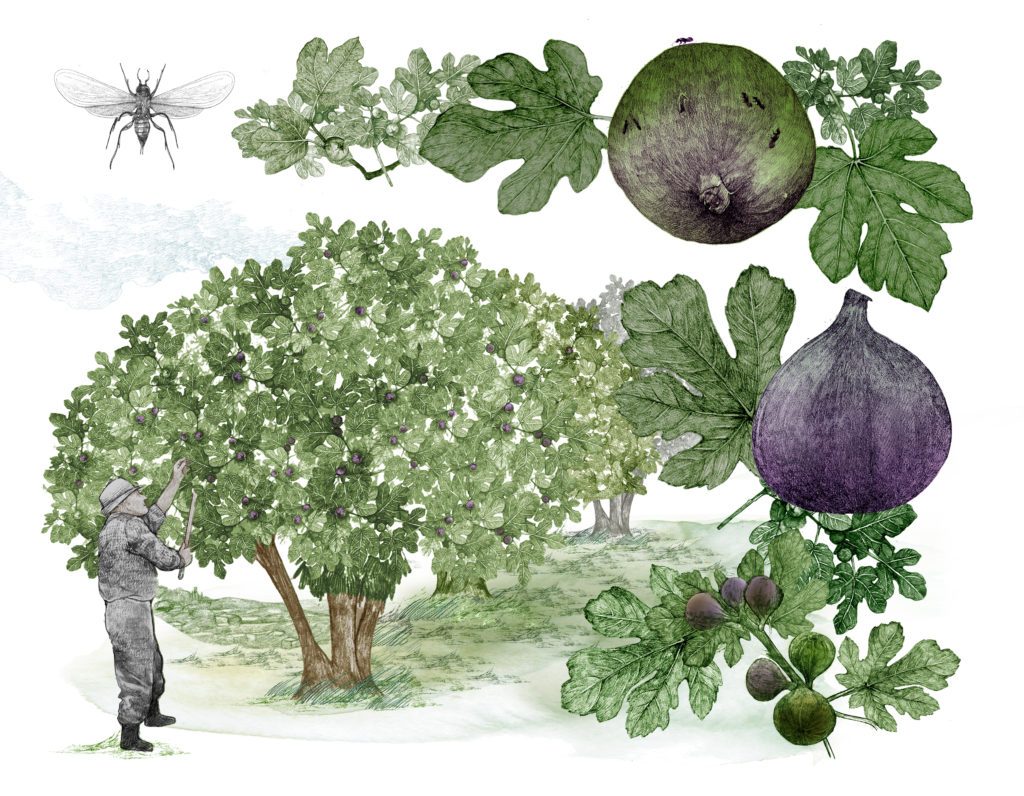

This book came recommended by a more botanically oriented acquaintance with the assurance that it’s not just for flora fanatics (flornatics?). When I saw it in a book store, I picked it up with cautious curiosity and was immediately won over by Lucille Clerc’s magnificent illustrations. Even if you decide never to read it, this book will automatically become one of the most beautiful volumes on your shelf.

Once you’ve lived with it a bit and been seduced by its beauty, I encourage you to read it and be transported on an incredible journey around the world. Jonathan Drori selects 80 representatives from the 60,000 or so species of trees alive today and introduces them to the reader in all their leafy wonder. Cleverly following in Phileas Fogg’s footsteps, the journey starts in London, where Drori is a former trustee of the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, and travels east to Southern Europe, the Mediterranean, and Africa. Next he goes to Asia, Australia, and South America, and finally to Mexico, the U.S.A., and Canada.

Drori enraptures the reader not just by explaining his subjects’ evolutionary

prowess and powers of adaptation, though he does this in many cases, such as in

describing the Sandbox of Costa Rica, whose seeds are too heavy to disperse in the wind and so have evolved a unique way of scattering their progeny: the seed pods explode under pressure, shooting the seeds out at a  speed of 230 feet per second. But Drori also makes trees endearing and accessible by describing their place in human history, both classic (as in the case of the Norway spruce and the Dragon’s blood, which were used to construct and stain Stradivarii, respectively) and current (as in the case of the Leyland Cypress, which are used as hedges in England and have resulted in tens of thousands of hedge disputes between neighbors). In some instances, folklore has built up a tree’s reputation, as in the case of Southeast Asia’s upas tree, whose toxicity has been greatly exaggerated by early indigenous peoples reluctant to reveal the true source of the poison weaponizing their darts to European settlers.

speed of 230 feet per second. But Drori also makes trees endearing and accessible by describing their place in human history, both classic (as in the case of the Norway spruce and the Dragon’s blood, which were used to construct and stain Stradivarii, respectively) and current (as in the case of the Leyland Cypress, which are used as hedges in England and have resulted in tens of thousands of hedge disputes between neighbors). In some instances, folklore has built up a tree’s reputation, as in the case of Southeast Asia’s upas tree, whose toxicity has been greatly exaggerated by early indigenous peoples reluctant to reveal the true source of the poison weaponizing their darts to European settlers.

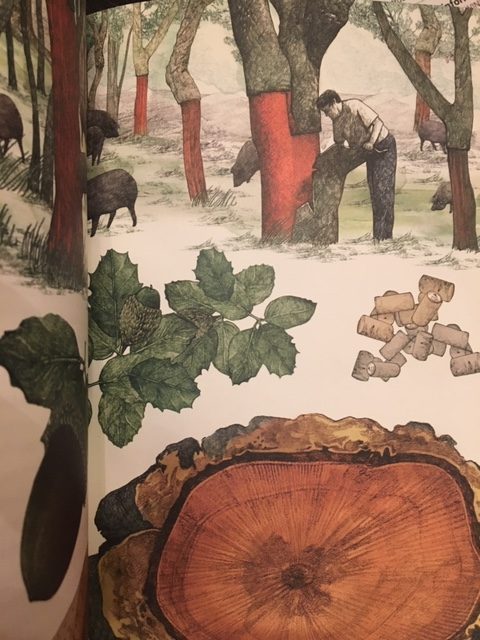

Drori’s writing style is delightful. Complementing an illustration of cork oak trees that have been partially stripped of their bark, he describes them as looking “curiously naked, like Englishman paddling in the sea, their trousers rolled up to expose reedy sunburned legs below.” He (or perhaps his editor) also helpfully provides conversions from metric to the Imperial measurements, for those of us who still can’t wrap our heads around the concept of meters.

Do you still think a book about trees can’t be entertaining? If you’re still on the fence, don’t take my word for it, take the word of satisfied reader Dame Judi Dench: “I have loved trees all my life. It’s fascinating to understand the key role they play, not just in our lives, but life as a whole.” Yes, a lady knight has a quote on the dust jacket, because that’s how British this book is.