I am (mostly) unashamed to admit that my first encounter with The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, or any of Mark Twain’s books, were not in school, but on my own accord after watching Disney’s 1995 “Tom and Huck.” I was twelve, smitten with the carefree, super hot (at least I thought so at the time) characters going on crazy adventures, and after the movie was over, I wanted more. I read Tom Sawyer first and loved it since the movie follows it fairly closely. I started Huckleberry Finn immediately after, but ninety-nine percent of the book went over my head. Written in dialect and the vernacular of the 1840’s American South, much of the story was lost to me simply because I had no idea what the actual words meant. The other one percent I spent mostly disgruntled that the Huck Finn of Twain’s original story bore zero resemblance to the hunky Brad Renfro adaption of the film. I got through it, mostly confused and somewhat disappointed in it, and didn’t think much about it after giving it back to the library.

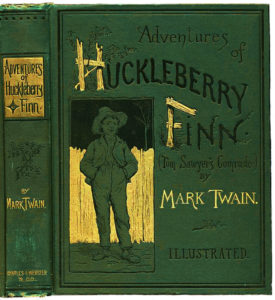

Since then, the censorship and controversy of the book has been tossed around the academic circles and classrooms of my career, and I’ve often considered returning to it since I didn’t remember understanding most of what the book was actually about. When browsing the bargain book barn, there was an entire shelf that was nothing but old copies of Huckleberry Finn, and since I try to read one classic a year, I decided 2019 was year I’d revisit this childhood disappointment. Would I be disappointed again? Would I be able to see it with fresh eyes like last year’s foray into Metamorphosis? Would I finally understand the controversies and censorship as an adult? The answer was yes.

Like all “capital-L” literature, Huckleberry Finn takes work to read, and should probably be read more than once. There’s the vernacular to decipher, understanding the context of the time in which it was written, and close-reading exactly what Twain’s doing with the words. I had no idea how to do this at twelve, so the reread was more like coming to this book for the first time. The story isn’t really a story, but a picaresque featuring Huck and Jim in vignettes threaded together by the Mississippi River. Twain spares no expense in showcasing the utter brutality and violence common in the 1840s, nor the way Huck’s society views slavery. Which, from very preliminary research, is where most of the controversy lies. Since it’s publication in 1884, libraries and communities have been banning or censoring Huckleberry Finn because it was too violent, and later on, too racist for children to understand. I agree that both are true; without some serious context and study, this book is violent and racist. But after researching a little on who Twain was as a person, I don’t think he ever meant this to be a children’s book. Twain’s choice to tell the story from Huck’s perspective allows him the leeway to showcase the ironies of this society in a way that hadn’t been done before. Huck’s a fourteen-year-old who’s been physically and mentally abused, swinging between raising himself and avoiding his drunk dad until some well-meaning townswomen step in. But he hates them more than his life in the gutter, in part because he doesn’t understand the societal structure they’re trying to impose. Their religion and morality baffle him because they don’t follow their own creed. The very structure of their society forces him to choose to be an outcast in order to do what he thinks is actually right. The only place he and Jim are safe is on the raft, floating in the middle of the river where civilization can’t reach them.

A question that often arises about this book, as with many other ‘classics,’ is should we still read them? Have they withstood time enough to still be relevant? For Huckleberry Finn, I would have to say yes, but with a caveat. Yes, we should still read this book because it’s easy to forget how history really was. It’s easy to paint a nice picture of a bucolic life on the river, and pretend that only people who owned slaves were the baddies, and everyone else was good, and just too powerless to do anything about it (which totally isn’t true). But one of the biggest assets of Huckleberry Finn is that Twain leaves nothing to the imagination on 1840’s societal reactions to slavery, race, and general morality. Reading this book is uncomfortable, because it should be. I think Twain meant it to be. But this book should also be read with extensive research of both the history of the time it takes place in, and the literary craft used to create it.

3 stars because slogging through an entire narrative of vernacular dialogue was awful.

Bingo Square: Classics