CBR11bingo: Classics

CBR11bingo: Classics

Have you ever gotten super into a television show in its second or third season, so you went back to watch it from the beginning so you could see what you missed, and then realized, “Huh. If I’d actually tried watching this from the pilot episode, I might not have been so interested”? (I’m looking at you, X-Files.)

A Study in Scarlet is sort of like that. Few works of literary fiction have spawned as many retellings, homages, and–dare I say–fantasies (and now I’m looking at you, Sherlock) as this novel. This year alone I’ve read multiple works inspired by Doyle’s famous detective. Yet the way I’d describe this novel, the one that started it all, would be. . . well, it’s perfectly adequate.

The novel begins with narrator John Watson describing the misfortunes he has endured as an army doctor serving in Afghanistan. While contemplating his limited funds (in a bar, while having a brew–way to stick to a budget, doc) and the need to find someone to share rooms with, he runs into an old acquaintance named Mike Stamford. Stamford tells him he knows a chap who is also looking for an apartment on a budget but warns his friend, “You don’t know Sherlock Homes yet. . .perhaps you would not care for him as a constant companion.” Stamford is more nervous than a guy who’s planning on setting up his wife’s sister with his high school buddy who still lives with his mother.

Wait, that’s been done, too?

As luck would have it, the pair get on well and move in together. At first Watson is mystified by Holmes’ livelihood, but he soon learns that Holmes is a detective of sorts, although he rarely leaves the apartment to do any real detecting. People come to him, tell him their mysteries, and he solves them without ever having to do any legwork. Until, that is, the murder in Lauriston Gardens!

Cue suspenseful music!

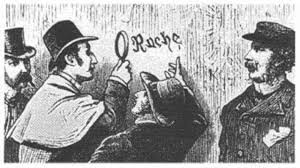

The body bears no sign of any injury, yet there are traces of blood, including that used to write an ominous message on the wall.

It’s either the name Rachel or someone left an angry note in German.

It’s a good mystery! Holmes makes some quick deductions to the amazement of not one but two baffled police inspectors. He finds clues, he drops hints, he sends a telegram. At the end of Part I, he magically produces the killer! And then. . .

Mormons!

Wait, what? Mormons? What are Mormons doing in a 19th century British mystery? And not even those funny Mormons who like Lord of the Rings and teach blasphemy to Ugandans.

If only!

No, these are the murderous, kidnapping variety of Mormons! (For the record, I don’t know whether this portrayal is accurate. I spent about five minutes on Wikipedia, but I’m honestly not interested enough in Mormons to pursue the matter any further.)

So yeah, Mormons. Part II of A Study in Scarlet explains the motive for the murder, which feels largely unnecessary. Doyle could easily have summed this section up in a couple of paragraphs and turned the novel into a short story. Maybe he had a book deal that required a certain number of pages? He couldn’t have just used a larger font and wider margins like a normal person? After the Mormon diversion, the novel shifts back to Watson’s voice, and we learn how Holmes solved the mystery: he had a hunch, and that telegram he sent prompted a reply that confirmed his theory.

Wait a minute, so the answer was in the telegram? That’s hardly fair play.

Smug, cheating bastard

In spite of it all, I guess the story isn’t what really matters. Sherlock Holmes is an extraordinary protagonist. He’s a collection of contradictions: Stamford describes his interest in science as “cold-blooded,” yet he also greets Watson with “a merry laugh.” He is a “first-class chemist” and an “analytical genius,” but of “contemporary literature, philosophy, and politics he appeared to know next to nothing.” When Watson compares him to Edgar Allen Poe’s Dupin, Holmes is insulted, as he considers Dupin “a very inferior fellow.”

The character of Sherlock Holmes is what drives everything else. The character is what inspired a fandom 130 years ago that still thrives today. Doyle famously grew tired of his creation, but the fans never did. To see the first glimpses of that genius makes A Study in Scarlet a worthwhile read.