CBR11bingo: Remix

CBR11bingo: Remix

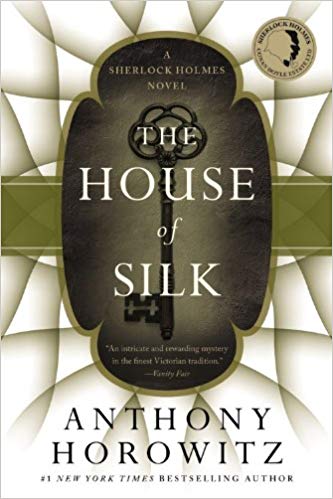

I recently had the good fortune to discover Anthony Horowitz, so my expectations were high when I picked up House of Silk, the author’s Sherlock Holmes mystery. I’ll get right to the point: He exceeded my expectations by a wide margin.

The estate of Arthur Conan Doyle commissioned Horowitz to write a Sherlock Holmes novel, and their faith proves to be well placed. Horowitz so beautifully captures the voice of John Watson, who characteristically tells the tale, that the novel slides effortlessly into the Sherlock Holmes canon. Horowitz puts the novel in context by explaining why we are getting a new Holmes mystery in the 21st century. In the Preface, Watson explains that it has been a year since Holmes has passed away (for real this time, not in the Reichenbach Falls sense). He is recording this tale now, because he could not tell it previously: it was simply too shocking. “When I am done, assuming I have the strength for the task, I will have this manuscript packed up and sent to the vaults of Cox and Co. in Charing Cross, where certain others of my private papers are stored. I will give instructions that for one hundred years, the packet must not be opened.”

The story proper begins with an art dealer named Edmund Carstairs, who approaches Holmes with a problem. Carstairs had sold some extremely valuable paintings to a client in Boston. Before delivery, however, the train carrying the paintings was attacked by an Irish gang led by the O’Donaghue brothers, twins Keelan and Rourke. Carstairs convinced his client to hire a Pinkerton detective to track the gang down, and Rourke was subsequently killed in a confrontation. Shortly thereafter, Carstairs’ buyer was murdered, and Carstairs high-tailed it back to England on the first ship out. Since that time, Carstairs has seen a mysterious man he believes to be Keelan O’Donague, who presumably followed Carstairs back to England to seek revenge for the death of his twin.

From this simple beginning, the plot, as they say, thickens. The mysterious man ends up dead, and the vicious murder of a street urchin (one of Holmes’ “Baker Street irregulars”) leads the detective and his biographer to a charitable school for orphans. But what, if anything, does a Boston street gang and stolen paintings have to do with a murdered orphan? The cast of characters broadens as well. We meet Catherine, Carstairs’ American wife, whom he met on the voyage from England; Eliza, Carstairs’ severe, spinster sister, who despises Catherine and even suspects her of trying to poison her (Eliza); Mr. & Mrs. Kirby, the Carstairs’ servants, along with their surly son Patrick; Sally Dixon, the sister of the murdered urchin, who is too terrified to speak to anyone. In addition, the regular cast of characters is present and accounted for, including Inspector Lestrade, Holmes’ loyal if slightly dim resource in Scotland Yard.

Horowitz does justice to Doyle’s characters and, dare I say, even tries to correct some of Doyle’s indifference towards his creations. Watson acknowledges poor, neglected Mrs. Hudson and admits that he should have given her more of a nod in the original stories. More poignantly, he alludes to his wife Mary’s illness and writes of his regret that he didn’t realize sooner that he was seeing the earliest signs of the illness that would eventually claim her life. “I have always had to live with the knowledge that I took her complaints too lightly and failed to recognize the early signs of the typhoid fever which would take her from me all too soon.” Kudos to Horowitz for rectifying, in part, the off-screen death Mary endured somewhere between Holmes’ “death” in “The Final Problem” and his return in “The Adventure of the Empty House.”

Mycroft Holmes also figures in the novel, although the depths of the crimes at hand run so deep that he warns his brother off the case, saying that if he (Sherlock) pursues the matter, he (Mycroft) can do nothing to help him. Nevertheless, Horowitz has fun with the brothers, as when they spar at deductions upon meeting. Sherlock begins:

“You did not tell me you had acquired a parrot.”

“Not acquired, Sherlock. Borrowed. Dr. Watson, a pleasure. Although, it has been almost a week since you saw your wife. I trust she is well. You have just returned from Gloucestershire.”

“And you from France.”

“Mrs. Hudson has been away?”

“She returned last week. You have a new cook.”

“The last one resigned.”

“On account of the parrot.”

“She always was highly strung.”

In spite of that bit of levity, Horowitz touches on more serious topics, such as poverty and the fate of criminals, in a way that exceeds Doyle. At one point, Watson ponders that his stories have always ended with the arrest of the criminal. He never really considered what happened afterwards, the walk to the gallows, the fear, the anguish, possibly remorse of those he helped to condemn. In a way he regrets casting them into a generalized bucket of criminality. Old age has made this Watson consider the stories he never bothered to tell.

Throughout the novel, and most movingly, the friendship between Holmes and Watson, that finest of bromances, pierces the plot like a beacon slicing through the fog of Grimpen Mire. As Watson lovingly writes: “Two marriages, three children, seven grandchildren, a successful career in medicine and the Order of Merit awarded to me by His Majesty King Edward VII in 1908 might be considered achievement enough for anyone. But not for me. I miss him to this day and sometimes, in my waking moments, I fancy that I hear them still, those familiar words, ‘The game’s afoot, Watson!'”

Indeed, I think we all miss him. For that reason, House of Silk is a true gift for any Holmesian.