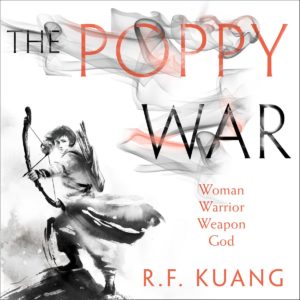

I hadn’t heard of R.F. Kuang until recently. It wasn’t until her name came up as John Campbell Award nominee that I decided to look into her work. And then I felt like a bit of a dill – because not only had The Poppy War been nominated for a John Campbell Award (Not quite a Hugo), but it had been nominated for a Nebula and a Locus Award as well. So I’m slightly ashamed I let her go unnoticed!

There was nothing for it – I was going to have to read this book.

Lucky for me, the publisher allowed it to be included in the Hugo Voters packet.

Rin, our protagonist, is an orphan of the second Poppy War who is attempting to enter the empire’s most prestigious military academy. She has motivation in spades – her none-too-loving adoptive family have been attempting to marry her off to a much older man for small town political gain, and she has no desire to pump out kids for him until he succumbs to opium addiction. Unfortuntaly the odds are stacked against her; unlike many of her contemporaries, Rin is a peasant and therefore has not previously experianced the level of coaching rich children receive in preparation for the Keju extrance exam. But thanks to her burning drive, the kindness (or extortion) of an old scholar, and perhaps a little opium bribe on the side, Rin does exceptionally well in the Keju, and is accepted into the most elite military school in the entire Nikan Empire – Sinegard.

While this is an outstanding achivement, this really only the first battle for Rin. Gaining entry is one thing – staying enrolled is a whole other matter. Rin is both poor and female, both of which are looked down upon by many of the staff and students. While Rin’s ambition alone may have been enough to keep her hanging on by the skin of her teeth, it takes the help of Jiang, the somewhat elusive Loremaster, to initially keep her on the narrow.

On our first impression, Jiang is presented as both a layabout and a scatterbrain; a man who is seen as a joke by the academy’s students and barely tolerated by his colleges. But there’s more him than meets the eye – Jiang is a Shaman, and like most shamans, he takes a ‘better living through chemistry’ approach of contacting and conducting the Gods. (Both of these together make for a more than adaquete explanation for his loopy behaviour). And because he takes a liking to Rin and belives she has the capacity to do great things, he induces her into Shamanism as well.

Rin makes for a compelling, but an obviously flawed protagonist. She’s highly determined and ambitious, but she’s still very much a teenager, strongly driven by her own anger. Rather than coming across as obnoxious – which is not at all uncommon for angsty teen protagonists – Rin’s anger is relatable. For another character, some of her choices would be frustrating – almost hair pullingly so – but for Rin, Kuang has given us a well of empathy, which you have to work hard at to empty. You see the same injustices she sees throughout the narrative, and can understand why she makes the choices she makes; even if you know they’re less than wise.

For the most part, the first half of the book follows a somewhat well-worn path in fantasy: where an orphan, against the odds, makes their way into a special school where they proceed to show the world how exceptional they are. But it would be a mistake to compare The Poppy War to Harry Potter. For Rin, this narrative comes abruptly to a halt when war breaks out with the Mungen Empire. She doesn’t even get a chance to sit her matriculating exams. And if the first half of the book follows a standard school fantasy, the second half makes a much bleaker turn; taking its cues from the Second Sino-Japanese War. The war between the Nikan and the Mungen is some of the grimmest I’ve read in a long while, and it’s not for the faint of heart. (If you know you’re history, you’ll have a good idea what to expect.)

Experiencing combat does not make Rin a seasoned soldier; she is still essentially a teenager, even with her shamanistic powers. And it’s not just her military skills that are still underdeveloped; her decision-making skills are still not fully mature either. Although she’s not able to admit it to herself, her judgements are still prone to being clouded by her anger.

An anger that goes unchecked under the duress of war.

An anger encoraged by another student.

And poor Jiang may not be able to pull a Yoda.

For a debut novel, The Poppy War is highly ambitious, and I can see why it’s raking up award nominations left, right and centre. R.F. Kuang does an excellent job taking a story that starts with a quite confined setting and expanding it in vivid detail. And while I think the very last part of the book is slightly less cohesive and perhaps a little too open-ended for my liking, I have since learnt that it’s not a stand-alone novel after all but part of a trilogy, which makes it a bit more forgivable.

And if Kuang is going to continue using early 20th-century Chinese history as an inspiration, I could see this story going in some very interesting directions.

Her next book will hopefully be out in August, and I think I’ll be putting in a pre-order.