I’ve never been the type to read more than one book at a time, but earlier this year, I decided I should both spend less time online and read more poetry and philosophy and mythology and the like. I kept one book on my nightstand to read before bed, another by my desk to read in downtime during work instead of picking up my phone. And it worked! I’ve spent much less time online and more time reading, but this success also led to an unintended side-effect: it’s sooooo much harder to review a book that took me six weeks to read in 15 minute chunks. I hope I’ll get used to it, because otherwise, it’s going to be a loooong year.

I’ve never been the type to read more than one book at a time, but earlier this year, I decided I should both spend less time online and read more poetry and philosophy and mythology and the like. I kept one book on my nightstand to read before bed, another by my desk to read in downtime during work instead of picking up my phone. And it worked! I’ve spent much less time online and more time reading, but this success also led to an unintended side-effect: it’s sooooo much harder to review a book that took me six weeks to read in 15 minute chunks. I hope I’ll get used to it, because otherwise, it’s going to be a loooong year.

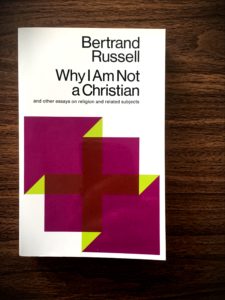

Bertrand Russell’s Why I Am Not a Christian contains essays written between 1899 and 1954, compiled by editor Paul Edwards in 1956 with Russell’s blessing, so instead of being conceived as a coherent whole, it’s a set of variations on the theme of Russell’s rejection of religion as moral philosophy. A famous mathematician and logician who won the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1950, Russell’s argument is simple: he is not a Christian (or adherent of any religion) because there is no scientific evidence to support the existence of any god. In his own words: “The world in which we live can be understood as a result of muddle and accident; but if it is the outcome of a deliberate purpose, the purpose must have been that of a fiend.”

Oof.

Beyond that, he argues on a number of recurring themes, including: “what does it hurt?” is a terrible justification for religion; religious practice and teaching harms children by witholding crucial information, especially in sexual education; arguments against birth control are inherently misogynistic; sin is defined by those in power; fear of death drives a lot of society’s problems; and religion is fundamentally regressive and anti-intellectual. Both Russell in his essays and Edwards in the introduction emphasize how important these discussions were at a time when religious fundamentalists are trying to roll back progress, and you realize not only how little has changed in the last fifty to one hundred years but how in some ways we’ve actually regressed. There’s also an intriguing appendix written by Edwards about the uproar after Russell was appointed Professor of Philosophy at the City University of New York in 1940, complete with a show trial where Russell’s opponents and the judge himself cherry-picked and flat-out invented evidence. Eighty years later, everything old is new again.

Having made it through all of the essays, I don’t believe Russell’s intent in any of them was to convince anyone of anything but instead to state his positions. I found the writing effective, though he often puts the same sort of blind faith into academics that he decries in the religious. His message isn’t going to convert anyone who isn’t already mostly converted: he’s far too sarcastic and dismissive and often condescending, even if I agreed with his underlying message. And that agreement is going to be crucial in determining how much mileage anyone gets from this book. If you identify with the title, then you might like it. If not, you almost definitely won’t.

On that note, I’ll close this review with the last line of the last essay, which I found the perfect summation of the entire book:

“What the world needs is not dogma but an attitude of scientific inquiry combined with a belief that the torture of millions is not desirable, whether inflicted by Stalin or by a Deity imagined in the likeness of the believer.”