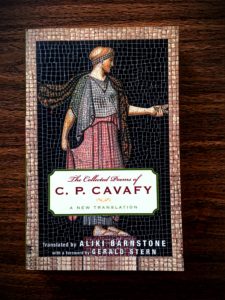

I know very little about poetry and even less about how to write about poetry, so to quote Prince, forgive me if this goes astray. I first heard of Cavafy when I was browsing through a book of gay love poems at Barnes and Noble back in my early twenties when I was first coming out. The simplicity of the poem made me think he was an ancient, perhaps the male equivalent of Sappho, but when I found this book, The Collected Poems of C.P. Cavafy, a few years ago and learned he lived in the 19th and early 20th Century, I was both surprised and not.

I know very little about poetry and even less about how to write about poetry, so to quote Prince, forgive me if this goes astray. I first heard of Cavafy when I was browsing through a book of gay love poems at Barnes and Noble back in my early twenties when I was first coming out. The simplicity of the poem made me think he was an ancient, perhaps the male equivalent of Sappho, but when I found this book, The Collected Poems of C.P. Cavafy, a few years ago and learned he lived in the 19th and early 20th Century, I was both surprised and not.

Cavafy’s poems fit broadly into two categories. The first are concerned with ancient Greek history, particularly the diaspora in Alexandria and the lands to the east of the Mediterranean. These poems would have seemed rather cold and cryptic without excellent and extensive notes by translators Aliki and Willis Barnstone that explain the people, places, and historical context. There’s much here that I would never have known otherwise, including a number of poems about Julian the Apostate, who was mentioned in Nick Harkaway’s Gnomon, a reference I wouldn’t have understood without reading Cavafy first. My favorites were “Waiting for the barbarians” and “Ithaka”, and it’s no wonder: the former inspired a novel of the same name by J.M. Coetzee, and the latter was requested by Jackie O to be read at her funeral.

The other major category of poems is concerned with gay love and eroticism. Lovely but often heartbreaking, filled with furtive glances, secret crushes, and fleeting beauty, Cavafy doesn’t mask these poems with metaphor as one might expect given the times in which he lived and wrote. Here’s one from 1917 called “I have gazed so long”:

I have gazed at beauty so long,

my vision is filled with it.

Lines of the body. Red lips. Sensual limbs.

Hair as if taken from Greek statues,

always beautiful, even if unkempt,

and falling, a little, on white foreheads.

Faces of love, just as my poetry

wanted them . . . in the night of my youth,

in my nights, in secret, found.

Then again, metaphor isn’t really his style. His poems are mostly brief and direct but filled with meaning, and even those that don’t fit neatly into those two main categories are still stylistically and thematically consistent with the others. They almost feel like fragments recovered from some ancient scrolls, these sublime miniatures, so it’s no wonder I didn’t realize he was a modern poet. I can see why he’s considered so influential and groundbreaking, but I also love that he’s so accessible, making for kind of the perfect bedtime poetry, where I could read one or two or ten, take my time to go over each a few times and read them aloud, and then fall asleep to thoughts of Greeks and clandestine love affairs.