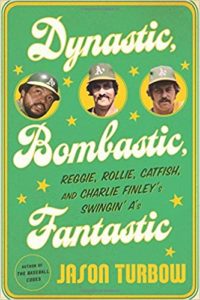

Every year I try to read a book or two about baseball during the long off-season. It feels a little more productive than looking out the window and waiting for spring. Jason Turbow’s Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic is a non-fiction account of the great Oakland A’s teams of the early-to-mid-seventies. For those of you who aren’t baseball obsessives, the A’s won three consecutive World Series, in 1972, ’73, and ’74. They had some all-time greats and All-Stars all over the diamond. Despite their advantages in talent and their many successes, the A’s were beset by constant in-fighting and never-ending controversy.

The main problem, as documented in Turbow’s book, was the owner of the A’s, Charlie O. Finley. A self-made man who earned his fortune in the insurance business, Finley wanted desperately to win but was equally desperate to get all the credit himself. He fired managers whenever they publicly challenged his control over the team and often stooped to undermining his own players performance when they were getting too much attention. He picked fights over salaries and insulted the play and the character of his players. The players themselves were prone to fistfights and publicly airing grievances in the press, but they managed to pull together against a common enemy: the guy who signed their too-small paychecks.

In the most famous incident of Finley’s personality turning everyone against him, his treatment of a veteran second baseman nearly caused his team to walk out in the middle of the World Series. When Mike Andrews made a couple of errors against the Mets in the 1973 World Series, Finley pressured him and the team doctor to fake a shoulder injury so he could be replaced on the roster. After hours of haranguing and being threatened with his release, Andrews signed a document attesting to the injury, but by then the real story was leaking out and the rest of the A’s were furious. They taped Andrews’s number on their sleeves and threatened to refuse to play unless he was reinstated. Eventually the commissioner ordered Finley to reinstate Andrews and when he came to bat in a game at the Mets’ Shea Stadium, the opposing fans gave him a raucous ovation just to stick it to Finley.

It wasn’t just his own players who hated Finley. Turbow shows in great detail how the A’s owner antagonized his fellow owners and the commissioner of baseball with his constant grandstanding and his litigiousness. Despite being in many respects a visionary who saw the future of baseball with a high degree of accuracy, Finley was rarely able to sell his fellow owners on his ideas. When he wanted to grant players free agency by giving every player one-year contracts every year, the owners thought he was insane, but the players’ union was terrified because they knew he had figured out that it was the scarcity of free agents that would drive up player salaries, not free agency itself.

Granted, some of Finley’s ideas were downright wacky. He thought orange baseballs would be easier for batters and fans to see at night, so he started using them one year in spring training one year without asking permission beforehand. The leather proved too slippery for pitchers to properly control their stuff, so the games featured tons of walks, hit batters, and plenty of home runs (he was at least right about them being easier to see.)

Eventually Finley’s toxic personality and the changing economics of baseball broke up the A’s. Players were traded, sold, or were lured away by other teams through free agency. Finley stubbornly refused to play market value for players or spend money to encourage fan attendance. As the players left and attendance, already low, sunk to new depths, Finley saw the dynasty he had built destroyed by his own hands, and was forced to sell the team.

Turbow’s book entertainingly chronicles the highs and lows, the triumph and the chaos of one of the greatest teams in baseball history.