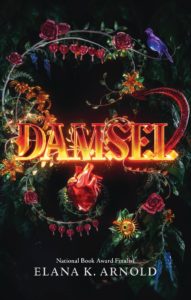

We open on a young man on a quest. He is the prince of his land and his father has just died. To claim his kingship, he must travel to the grey land, defeat a dragon, and bring back a damsel for his bride. This is how things have always been in Harding. The farther dies and to claim his place, the son must complete this rite.

Tradition in Harding decrees that the prince can be give no help to defeat his dragon, not even in the form of advice. But the prince picks up tidbits through gossip and prepares as best he knows how, practicing hunting, arms, and the type of conquests that involve a (reluctant) maidservant and a deserted hayloft. His mother (once a damsel herself) sends for him each day, to hear of his achievements and praise him. He omits any hayloft adventures, though he thinks she must know and approve of his manly pursuits.

The day the prince’s father dies, his mother sends for him once more. She breaks with tradition, telling him he has two weapons to fight the dragon (his mind and his sword) but that to win the day, he will need a third. We see the prince enter the dragon’s castle, using cunning and steel to bring the dragon low, as he frantically thinks what his third weapon could be.

We open again on a young man, his quest now finished. The naked damsel lies in his arms, no memories of her past in her head. “I rescued you,” the prince tells her. He defeated the dragon and carried her down the cliff to bring her home as his bride. He gives her clothes and food and a name (Ama, because women’s names should start with a soft sound, he says); he is handsome and strong, this must be her destiny.

Ama enters the prince’s castle and begins to learn what her role will be. She is to be beautiful and compliant, silent and submissive, eager to please her king. She should seek the king permission to walk in the garden, she shouldn’t admit she knows she’s beautiful, she should ready herself for her wedding night. Women are vessels, the king tells her, to be filled by men. It is her duty to listen, he says, and his to speak. She must wait, he will take action; she admires, he creates.

Distressed at this picture of her future, Ama seeks council and kindness from those around her.

“Wild creatures must be broken so they can be tamed,” the falconer, the king’s best friend, tells her.

“You’d better pretend to enjoy it, because the king will be angry if you don’t,” the reluctant maidservant tells her.

“If you marry my son, I will die when his seed is planted in you, as all queens do when the new damsel takes their place.” the queen mother (who, if you do the math, is only thirty-two) says. “If?” Ama ask. “When,” the queen says. “If,” Ama thinks. “If, if, if.”

Damsel is a familiar story in many ways. The handsome prince rescues the damsel in distress and is rewarded with her heart. Tale old as time. So is the other story being told. That of young women penned in by the rules and expectations forced on us, constantly told what we should and shouldn’t do, what we can and cannot be. Told that it is our job to fulfill men, how to make men feel smart and wanted and strong, we must make ourselves soft and gentle and weak. It’s a story women know deep in our bones. But do we know how that story will end?

We open on a young man on a quest. How will we close?