“The point is what you do when you don’t have the details. Do you interrogate? Do you examine? Or do you settle for the obvious answer?”

“The point is what you do when you don’t have the details. Do you interrogate? Do you examine? Or do you settle for the obvious answer?”

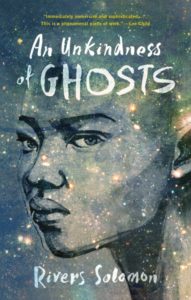

Most people don’t deeply question (cough, Kanye, cough) why enslaved people “allowed” themselves to remain enslaved. But most of us also don’t dwell deeply on what systematic physical and psychological trauma would be needed to keep a whole class of people oppressed and how that trauma may ripple out generationally. And why would we? Envisioning something like that is painful and requires a certain amount of tenacity to push through. Especially so if the reader is part of a marginalized group themselves and already acquainted with systemic oppression. Thankfully, Rivers Solomon has done the work for us and crafted the perfect trojan horse in the form of An Unkindness of Ghosts, a novel that that lures the reader in with a mystery set on a generational “self-sustaining” spaceship.

Set aboard a claustrophobic and aging spaceship, the story picks up 300 years into the ship’s journey. It’s revealed that the ship and some portion of humanity left earth because of environmental strains (overpopulation, pollution, etc) and that the original plan was for the ship to leave, and then return several generations later to a healthier planet. At some point during the journey, the black ship members ossified into a permanent slave system. They are separated into castes based on color with the lightest living on higher decks with better access to resources, while the darkest ones live on the bottom levels and are most vulnerable to extreme living conditions and little to no resources. Ruled over by white guards and a white ruling caste the black ship members are constantly at risk from their physical, mental and sexual whims, all the while being compelled to do the bulk of the work to keep the aging ship working and the ruling class cared for and fed. Aster, our protagonist, is our guide through this world as they slowly realize their mother’s death was not the straightforward suicide they had been told. Instead, Aster’s mother’s death 21 years ago is somehow connected to the current sovereign’s sudden illness and multiple other secrets on the ship.

Normally, I avoid fiction that dissects the slave experience because I’m black and well versed in black suffering already. But this novel broke through my reserve because it, unlike many fictional slave accounts, the text is not centered in any way on the oppressor’s perspective or feelings. Instead, Rivers Solomon, a non-binary queer person, centers the story on Aster, a dark-skinned orphan, who seems to also identify in the same way.

“I am a boy and a girl and a witch all wrapped into one very strange, flimsy, indecisive body. Do you think my body couldn’t decide what it wanted to be?”

One of the many highlights of the novel is the organic representation of gender and sexuality aboard the ship. Aster’s white-passing mentor is trans-femme, while the “auntie” who raised Aster after her mother’s death is indicated to be aromantic or ACE. The backgrounds of all of these characters are key as it gave Solomon a way to show the reader how dependent slave systems are on pushing white cis-heteronormativity as a tool to retain power.

For a debut novel, this was a stunner. It was fully formed and sure-footed in a way that would indicate a more seasoned author. The way Solomon handles sexual and physical assault from the survivor’s perspective should be used as a masterclass for other authors.

This was probably one of the hardest novels I’ve actually finished in the recent past but I’m really glad I got over my initial reluctance to pick it up.