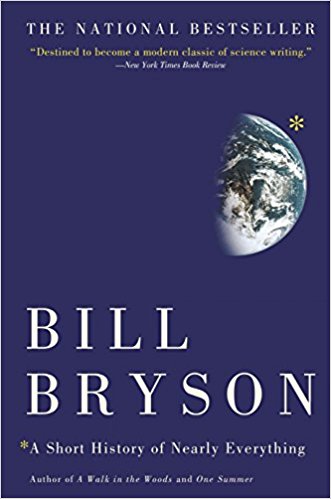

Although probably best known for travel writing, Bill Bryson has written a number of science-based nonfiction books, and in 2003 he published a book that pondered the scientific questions and attempted to answer, well, nearly everything. The jump from travel writing to his Short History of Nearly Everything is not such a tremendous leap, however, if you think about it like a travelogue, starting with the beginning of the solar system and ending with life as we know it.

Although probably best known for travel writing, Bill Bryson has written a number of science-based nonfiction books, and in 2003 he published a book that pondered the scientific questions and attempted to answer, well, nearly everything. The jump from travel writing to his Short History of Nearly Everything is not such a tremendous leap, however, if you think about it like a travelogue, starting with the beginning of the solar system and ending with life as we know it.

In the introduction, Bryson describes how he came to write this book, starting with his experiences studying science in grade school. It seemed to him that just as topics started to get interesting, text books always let him down, failing to answer the questions that burned in the mind of a curious fourth grader. He writes, “All [my textbooks] were written by men . . . who held the interesting notion that everything became clear when expressed as a formula and the amusing deluded belief that the children of America would appreciate having chapters end with a section of questions they could mull over in their own time.” As a result, Bryson grew up thinking science was boring and avoided thinking about it all for quite a long time. I can relate to this: as a product of a Catholic school education, I’ve often regretted how long into my adulthood it took me to appreciate science. It’s a little ironic, I think, that Gregor Mendel, father of modern genetics, was an Augustinian monk; meanwhile, science at my school was being taught by nuns who thought the earth was 4000 years old.

Save time by covering science and religion in the same class period!

I digress. As I said, this book tells the story of earth and life on it, starting with the cosmos. I have to admit, astronomy and astrophysics are not my strong suits, nor are they my key areas of interest. No offense to Neil deGrasse Tyson; he seems like a cool guy and an inspirational scientist, but I glazed over about 10 pages into Astrophysics for People in a Hurry. Nevertheless, Bryson does an admirable job making the topic interesting by telling the stories of the 17th and 18th century scientists that were studying celestial problems. According to Bryson, Edmond Halley, most well-known for the comet named after him, once made a friendly wager with Robert Hooke and Sir Christopher Wren, challenging them to come up with the solution to why the planets orbited in an elliptical pattern (this much was known, but the why eluded the great minds of the day). Hooke claimed to know the answer already but declined to share because “it would rob others the satisfaction of discovering the answer for themselves.” He reportedly then turned to Wren and said, “Chris, why don’t you tell me what you think the answer is, so I can make sure you understand it.”

Damn Neil deGrasse Tyson thinks he’s better than Robert Hooke.

From the study of celestial bodies, Bryson moves on to atoms, and this is where my brain really can’t keep up. Because atoms are so durable, they really get around, and all our atoms were probably once floating around in space passing through stars and becoming part of previously living people and other organisms before they landed in your body. So I guess people who claim to be reincarnations of someone famous and brilliant aren’t necessarily full of crap.

And yet, nobody ever claims to be the reincarnation of slime mold.

The chapters on life and evolution are the most interesting to me. There’s so much to say on this topic, I couldn’t possibly do it justice, but I like how Bryson sums it up, “Whatever prompted life to begin, it happened just once. That is the most extraordinary fact in biology, perhaps the most extraordinary fact we know. Everything that has ever lived, plant or animal, dates its beginnings from the same primordial twitch.” Bryson also emphasizes the mistake people often make in thinking that humans are the culmination of all that previously happened in the universe. That we are alive and at the top of the current food chain is our shear luck that a billion billion things happened a certain way to make earth habitable for us. To think this is going to last forever is naive. We are a blip on the universe’s clock; life came before us and will likely continue after in some other form.

That this book covers nearly everything is both its strength and its weakness. It’s an outstanding intro to science for the non-science minded. However, I would have preferred several longer books on the topics that most interest me. My other caveat in recommending this book is that it is 15 years old, and new scientific discoveries are made all the time. I’d like to see a follow-up to this book, or perhaps a new edition with an afterword that addresses any assumptions that might be out of date.

One thing about science, it puts one’s metaphysical reflections into perspective. As Bryson writes, “It is easy to overlook this thought that life just is. As humans, we are inclined to feel that life must have a point. We have plans and aspirations and desires. . . . But what’s life to a lichen? Yet its impulse to exist, to be, is every bit as strong as ours–arguably even stronger.”

Boo hoo to you and your mid-life crisis. I’ve had the same job for 400 million years and you don’t hear me whining.