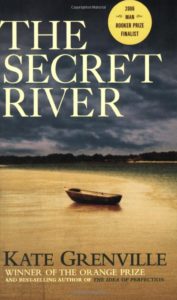

Last summer I helped my boss chaperone his student study-abroad trip to Australia, and the class read this book on the plane going over. I was far more enticed with Air New Zealand’s extensive on-flight entertainment package, and so I spent my plane ride in the iron-a** challenge watching all six (extended) Lord of the Rings and Hobbit films instead. Since returning, my boss has been passively placing The Secret River in obvious places on my desk, which I’ve learned is his silent way of saying it’s a book I really need to read. He’s adorable, my boss. Bingo seemed a great reason to finally pick this up and give it the attention it deserved, and to my boss’s credit, it was indeed something I needed to read.

At its core, The Secret River is a damning tale of how England’s use of Australia as a penal colony caused the genocide of the Aboriginal tribes and their way of life. However, Grenville is sneaky in her craft and chooses to tell this story not from the point-of-view of the Aboriginals, but of the prisoner, Will Thornill. And it works. Brilliantly. We follow Will from his terrible childhood in the poorest sections of London, through his marriage and the beginning of him making a way out for himself, to his demise when the money runs out and his subsequent fall into theft. This leads to his whole family being vomited out on Syndey’s overgrown shores. Grenville is a slow writer, building her characters deftly and carefully. Truthfully, I almost DNFed this at the half-way point because it felt so slow, but there’s something in the painful beauty of her prose that made me keep going.

Until about the half-way point of the book, the Aboriginals aren’t even mentioned, and I started wondering what kind of story Grenville was trying to tell, but as the second half of the book unfolds, her craft made brilliant sense. When Will moves his family onto an unclaimed plot of land along the river, and they try to carve a life out, they run into the Aboriginals who are already ensconced there, and the ever present racism of white people meeting non-white culture begins. But Grenville tells it from Thornill’s perspective. He tries to be friendly (in his mind), tries to make peace, tries to live alongside them without making a bother, and it doesn’t work. In reality, we see Thornhill make no effort to learn the Aboriginal language, ask no questions about the land or learn about their culture, and make no effort to figure out how to live in the land using the techniques of the people who are already inhabiting the space. He even goes so far as to forbid his one son from being friends with Aboriginal children, and he consistently belittles their names and culture while they take an active role in trying to unravel his. We hear what Thornhill says, what his neighbors say, but we also get to see what they do, and the twain never meet.

As readers, we know where this ends before it gets there, and perhaps that was part of the pain of this read, was to see all the places where fear was the reason for murder. Every time something escalates in this plot, fear precedes it. The aboriginals are just doing what they do, but the ‘otherness’ of their rituals and daily-living is terrifying to the colonists, and so it is deemed a threat. Something to be gotten rid of. A pestilence. The colonists don’t perceive their own issue, their own discomfort and vulnerability in a strange land so far from anything they’ve known. They were small fish in a big pond back in England, but they have the opportunity to be big fish in the little towns of Australia. And they take that chance. Thornill treats the Aboriginals as he was treated in England: lesser-than, perpetuating the cycle of authority and ownership from one continent to another.

Grenville’s story shines an interesting light on how racism grows and flourishes no matter what part of the world we turn to, and I found it to be an enlightening look on the past in a way that completely parallels the present.

4 stars.

Bingo Square: Snubbed