CBR Bingo entry Throwback Thursday.

CBR Bingo entry Throwback Thursday.

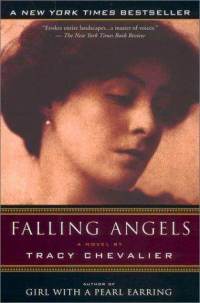

I read this novel many years ago at the recommendation of our Ms. Was (whether she remembers or not!), and it completely won me over. I know, everybody loves Girl with a Pearl Earring, and I do as well, but Falling Angels is still my Chevalier of choice.

Bracketed by the funerals of Queen Victoria and King Edward VII, the novel spans 9 years in the lives of two London families, the Colemans and the Waterhouses, as the world around them evolves. At the start of the novel, the families meet in a graveyard the day after Queen Victoria dies. You’re not imagining it–that right there is a pretty significant bit of foreshadowing. I’m going to come right out and say that from the earliest pages of this novel, you can feel it marching relentlessly toward tragedy. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

After exploring the cemetery together, the two young daughters become friends in the way only children can–accepting a playmate with whom they obviously have little in common. The next decade sees the rise of the suffragette movement in the U.K. and a tension between those looking forward to a new society and those entrenched in the old ways. Before the decade is over the families will share not only tragedy, but blame.

I said this novel is about two families, but that’s misleading since it very much belongs to the females. As the point of view shifts between characters with each chapter, we get some insight into the perspectives of both family patriarchs, but they are mostly relegated to observer status in the drama that unfolds. Richard Coleman and Albert Waterhouse are products of the Victoria Era and subscribe to the philosophy that there’s men’s business and women’s business, and it’s best not to mix the two (although Coleman most definitely figures into some of the more salacious details of the novel). The exception to this is Simon, the son of a gravedigger, whom the daughters meet that first day in the cemetery. It’s true that he too is an observer, but he also becomes the girls’ confidante and serves almost as a Greek Chorus of sorts to the rest of the characters. For all his lack of education, Simon seems to see and understand more than everyone else. This sounds like a hackneyed technique, but it works.

As I said, the women own this narrative, and like all good characters, most are deeply flawed. Gertrude Waterhouse, traditional wife whose desires end at her own doorstep, dotes on her spoiled daughter Lavinia, raising her to be as simple and unambitious as her mother, though perhaps with greater smugness and self-importance. Kitty Coleman is discontent, seeing her marriage and role of wife and mother as a prison she went into willingly but now regrets. She would be a more sympathetic character if she weren’t so emotionally distant toward her daughter Maude. Of Maude’s birth, Kitty recalls, “Of course I loved her–love her–but my life as I had imagined it ended on that day. It led a low feeling in me that resurfaces with increasing frequency.” Maude, for her part, manages to thrive in spite of her mother’s negligence, turning away from sentimentality and towards science. Her interest in astronomy signals that she’ll be the one to move forward, to forge ahead into the next era.

We also hear the voices of some minor characters (again, mostly women), including the Coleman’s too-worldly-for-her- own-good maid Jenny and Kitty’s domineering mother-in-law Edith. One of the most poignant inclusions is Ivy-May, the younger Waterhouse daughter, who narrates a single, two-sentence chapter that proves to be as heartbreaking as it is pivotal.

From the suffragette movement to women’s control over their bodies, this novel is very much about the rights of women. That it’s set at the turn of the Twentieth Century makes the control by men more obvious, but I couldn’t help scratching my head wondering how far we’ve really come. Aren’t there still women who trust their husbands to make decisions for them, like Gertrude? And women who feel trapped and desperate, either by societal expectations, like Kitty, or by economic limitations, like Jenny?

Fortunately there are also Maudes, who give the novel (and myself?) hope. The women’s suffrage movement in the U.K. resulted in two laws, in 1918 and 1928, that finally gave women equal voting rights to men. The young women of this novel would be among the first generations of women to be able to vote. In spite of tragedy and heartbreak, progress creeps slowly forward.