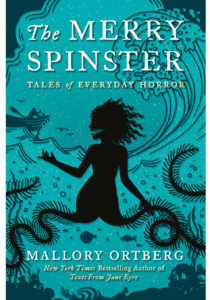

As I have mentioned before, fairy tales were my jam when I was younger. I also love some good remixes — musical or cultural — and humor, so things like Texts from Jane Eyre were absolutely delightful to me. When I heard that Daniel Mallory Ortberg was putting out a book of retold fairy tails (as Mallory Ortberg), I immediately put in a pre-order. In my haste and my assumptions based on the humor of Ortberg’s other work, having missed the “Children’s Stories Made Horrific” series on The Toast, I foolishly disregarded the “tales of horror” part of the subtitle.

As I have mentioned before, fairy tales were my jam when I was younger. I also love some good remixes — musical or cultural — and humor, so things like Texts from Jane Eyre were absolutely delightful to me. When I heard that Daniel Mallory Ortberg was putting out a book of retold fairy tails (as Mallory Ortberg), I immediately put in a pre-order. In my haste and my assumptions based on the humor of Ortberg’s other work, having missed the “Children’s Stories Made Horrific” series on The Toast, I foolishly disregarded the “tales of horror” part of the subtitle.

Turns out, that part was not a joke or an exaggeration. Many of the stories are slow burns of dread or a gut punch or both. Perhaps I’m extra sensitive due to current news and topics of common discussion, but the power imbalances and predatory figures struck a wildly uncomfortable chord with me. Some, like “The Daughter Cells,” a play on The Little Mermaid, are not so bad in that the unpleasantries stem more from cultural disconnects between species and their differing priorities and values. Certainly it still swerves around a fairy tale happy ending (perhaps more of a fairy tale Grimm ending), but there isn’t really any malice to it. Similarly, “Fear Not: An Incident Log” undeniably traffics in wide misfortune upon mortals (it is told from the point of view of a Biblical messenger angel with a decidedly immortal view of human suffering and fragility) but still retains a purposely uncomprehending lightness about it.

Other stories are much more aware of the problems facing the protagonists, particularly those laid by emotionally manipulative and consciously abusive characters like the stepmother in the Cinderella-esque “The Thankless Child” or the beastly Mr. Beale in the Beauty and the Beast-inspired “The Merry Spinster.” Even when the main characters come across as oddly empty in the faces of gaslighting and guilt-tripping, it reads as a deliberate blanking of the self as a defense mechanism rather than a lack of personality or the courage to fight back.

Ortberg repeatedly subverts expectations in all manner of ways. Characters respond to situations with unromantic pragmatism, selfishness, or even just an understandable desire for self-preservation, all of which are lacking in many classic fairy tales in ways I did not notice before. The prose also plays on notions of gender, often for no apparent reason, but why not? There are daughters named Paul, sons named Sylvia, princesses who use he/him/his, and couples who, once they are married, casually discuss who will be the husband and who will be the wife. (“I didn’t know if you wanted to be a wife or not so I guessed, but we can still change it. I’m trained for both, if that helps.” “Oh, I don’t mind.”) After all, if a frog can talk and a tree can bestow gifts, why can’t gender shift like a sea princess growing land legs?

And a few of the stories are truly unsettling. For all that I found The Velveteen Rabbit boring and overly sentimental as a child, the sociopathic slow burn of “The Rabbit” ramped up the crawling dread in a way five-year-old me would never have wished. But top prize goes to “Cast Your Bread upon the Waters” and its religiously fanatical narrator. I won’t add any details so as to avoid spoilers, but it seems a veiled exploration of the mindset of parents who force their LGBTQ+ children through conversion therapy, and it, quite frankly, messed me up. As in, I am writing this review a couple weeks after finishing the book, and I’m still vaguely queasy when I think about this story.

I didn’t expect for a book of slightly surreal little tales from an author I mostly associated with humor and snark to get under my skin so much, but there you have it. Many of the themes feel uncomfortably familiar given recent news topics, but none of it feels forced or heavy-handed. They quietly pervade the stories the way they permeate lives, and then the stories settle softly next to you, watching a little too long, breathing a little too close.