Perhaps you have heard of Ruby Bridges, the little girl shown at right.

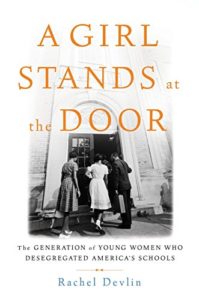

Perhaps you have heard of Ruby Bridges, the little girl shown at right. She was the first African American child to desegregate an all-white elementary school in 1960. But have you heard of Lucile Bluford or Ada Lois Sipuel? What about Marguerite Carr, Karla Galarza, Barbara Johns, Betta Bowman and Elaine Chustz? In Rachel Devlin’s A Girl Stands at the Door: The Generation of Young Women who Desegregated America’s Schools, we have an outstanding history of the unsung heroes of the American Civil Rights movement — the young women and girls who sued school districts and volunteered to be the “firsts” to desegregate American schools. Devlin tells the stories of a number of young women, many still alive, whose names have by and large been left out of history books but whose actions changed the country for the better. This is a story of personal conviction and bravery as well as family and community support. It is a story of the grassroots pushing for integration not just against the will of white power and authority (see Elizabeth Gillespie McRae’s Mothers of Massive Resistance), but sometimes even against the preferred agenda of the NAACP.

She was the first African American child to desegregate an all-white elementary school in 1960. But have you heard of Lucile Bluford or Ada Lois Sipuel? What about Marguerite Carr, Karla Galarza, Barbara Johns, Betta Bowman and Elaine Chustz? In Rachel Devlin’s A Girl Stands at the Door: The Generation of Young Women who Desegregated America’s Schools, we have an outstanding history of the unsung heroes of the American Civil Rights movement — the young women and girls who sued school districts and volunteered to be the “firsts” to desegregate American schools. Devlin tells the stories of a number of young women, many still alive, whose names have by and large been left out of history books but whose actions changed the country for the better. This is a story of personal conviction and bravery as well as family and community support. It is a story of the grassroots pushing for integration not just against the will of white power and authority (see Elizabeth Gillespie McRae’s Mothers of Massive Resistance), but sometimes even against the preferred agenda of the NAACP.

If you grew up in the US, at some point in a US history class you learned about Brown v. Board of Education, the famous case argued by Thurgood Marshall before the Supreme Court (1954) which argued that separate but equal is not equal, that racial segregation in education is unconstitutional. It was a groundbreaking decision and helped earn Marshall much deserved accolades for his work on behalf of the NAACP and people of color across the nation struggling to attain equality. Historian Rachel Devlin provides some much needed context for this decision and its aftermath, pointing out a curious fact that has been ignored in history books: before the Brown decision, quite a number of desegregation suits had been filed within states and on the federal level, and the vast majority of those suits featured young women and girls as the plaintiffs. After the Brown decision, young women and girls formed the majority of the volunteers who stepped up to integrate white schools. They were invested and committed to fighting, often alone, for desegregation. Why? What kind of person is willing to take on this burden? To examine this question, Devlin begins with the early cases for desegregation. In the 1940s, cases for desegregation in education focused on graduate school admission. Plaintiffs would be college graduates attempting to break the color barrier to enter law schools and other professional schools at state institutions. The NAACP was actively involved in many of these cases in which plaintiffs were often men. Yet two of the most successful and best known cases involved women. Lucile Bluford, editor-in-chief of a widely read and respected black newspaper called Kansas City Call, fought for admission to the University of Missouri’s School of Journalism. Ada Lois Sipuel fought for admission to the law school at the University of Oklahoma. While male plaintiffs in desegregation law suits often expressed satisfaction with being offered entry into separate but equal programs, Bluford and Sipuel refused to accept anything less than acceptance into segregated white institutions. The US Supreme Court ruled in Bluford’s favor in 1942, but the University of Missouri closed their journalism program rather than let a Black woman enroll. Sipuel likewise won her case in 1948, attended law school and passed the bar in 1950. Ada Lois Sipuel was the first Black lawyer in Oklahoma who was trained in Oklahoma, and she became an inspiration to Anita Hill.

The NAACP played a role in both cases, but their support seemed at times reluctant or muted. Devlin gets into some of the political concerns that affected NAACP involvement in these early desegregation cases. One issue was money. Filing and fighting court cases was and is expensive, and the NAACP preferred to focus on cases that arose in states with well funded chapters, such as Texas. The other issue was whether plaintiffs should settle for promises of a separate but equal graduate education (equalization of black institutions) or push for desegregation. In some early cases, the NAACP supported suits where the plaintiffs (men) were willing to settle for equalization. Also, male plaintiffs sometimes had difficulty handling the pressure of lawsuits that gained statewide and national attention. Plaintiffs in desegregation suits had to be able to handle hostile cross examination in a courtroom and in the press. They also had to be willing to travel and speak with friendly groups who supported the cause. Desegregation suits frequently brought negative repercussions to the plaintiffs’ families and themselves, such as loss of employment and threats of violence. Being a woman, however, did not insulate a plaintiff from these same repercussions. Why would Bluford and Sipuel put themselves through it? Devlin provides readers with extensive background information on them, and what we learn is that not only were they hardworking, intelligent women, they were also committed to the rightness of their cause. They understood, as did the young women who would follow them, that what they were doing was not just for themselves. They knew that every time they appeared in public and spoke, they were representing their race, and their parents had raised and prepared them to always act appropriately. They had impeccable manners and were able to answer questions in direct ways that disarmed the questioners. Their diplomacy skills were formidable as was their ability to endure the harassment that would follow them.

This sense of serving a greater good, the ability to serve as positive leaders and endure harassment are hallmarks of the grade school and high school girls who would follow in their footsteps. In the late 1940s, thanks to stories run in papers like Bluford’s Kansas City Call, grassroots support for desegregating elementary and high school education began to grow despite the NAACP’s desire to maintain focus on higher education. Devlin gives details on numerous suits that originated from within small communities, and usually the plaintiffs were girls. Obviously, the parents of these children would have been the reason for the suits to start, but the young women and girls in whose names the suits were filed report that they wanted to get involved. Again, they felt that they were serving a cause bigger than themselves, and they also had the chance to be leaders in ways that traditional society did not allow. They had to look right, behave perfectly, and always give the right answer to questions from lawyers and the press. Again, males often shied away from being involved in the suits and later in the move into white schools. Devlin’s chapters on the move to integrate all-white schools in the 1960s are full of incredible details from the memories of the young women who boldly stood at the door surrounded by jeering students, parents and teachers. They were intimidated, harassed, bullied, physically harmed, but they all agree that the worst thing was their isolation within these schools. Even within their own communities, some questioned their motives in volunteering to go to white schools (you think you’re better than us, you want to be white, you’re preventing our own Black schools from being better). In her interviews with these “firsts,” Devlin also asks about their experiences after high school and the impressions that their activism left on them. Their reactions are varied but overall, they are proud of their activism and have no regrets.

A Girl Stands at the Door reveals an important chapter of American history that has been left out of texts. These young women and girls of color, their families and the communities that supported them, are the greatest generation. Devlin’s research and description of their contributions to desegregation is invaluable and long overdue. Read this along with Elizabeth Gillespie McRae’s Mothers of Massive Resistance to understand the reasons we are still fighting racism today, particularly in education, and the power of grassroots organization and women’s voices for both good and bad.