Reading this book, I was reminded of a moment near the end of season 3 of Top Chef, when Casey presents her dish to the judges as a coq au vin inspired by memories of her grandmother. Tom Colicchio scolds her for calling the dish coq au vin when it wasn’t, but he also tells her it was a good dish and probably would have won the challenge if she had just called it what it was: chicken braised in wine. The moral of the story: expectations are important, and words matter.

Reading this book, I was reminded of a moment near the end of season 3 of Top Chef, when Casey presents her dish to the judges as a coq au vin inspired by memories of her grandmother. Tom Colicchio scolds her for calling the dish coq au vin when it wasn’t, but he also tells her it was a good dish and probably would have won the challenge if she had just called it what it was: chicken braised in wine. The moral of the story: expectations are important, and words matter.

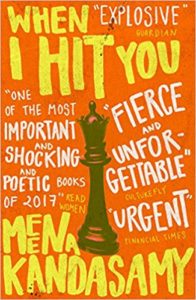

I wish Meena Kandasamy hadn’t called When I Hit You a novel. Call it a novel-length poem. Call it a memoir in the form of a novel-length poem. Call it a one-woman show in book form. (I can totally picture her standing on a stark stage, performing this story to a silent, weeping audience.)

As any one of those other things, this book is a brilliant but unrelentingly brutal examination of an abusive marriage. The emotional, physical, existential pain she experienced is palpable, visceral. She writes with vivid, powerful, poetic language, and then she digs into the linguistic origins and implications of the language she uses to write and the language her husband uses to abuse her, writing at one point, “I’m ashamed that language allows a man to insult a woman in an infinite number of ways.”

She also knows the questions her readers are going to ask, and she answers them directly. Around two-thirds of my way through, I found myself wondering if she overplayed her hand, making the husband character too cartoonishly evil, making herself too weak in spite of her own feminism and education level. And rightfully so, she shamed and embarrassed me over and over by directly addressing my exact questions, batting aside the victim-shaming mentality so deeply ingrained in cultures around the world. I’ve been on a mission to read more books by women this year, and this particular book perfectly illustrated why it’s so important.

As a novel, it isn’t as successful. There’s not a lot of character development. There isn’t much of a story arc. There’s a lot of explanation, especially in the dénouement. There’s not even much dramatic tension. We know his abuse is going to escalate, but we also know that she survived to write this book. She even talks about writing and publishing an essay about her marriage, which she clearly expanded into this book. But I was bothered most by Kandasamy’s obvious expectation that the reader accept this book as a true story. (My college English lit professor would wag her finger at me for assuming the narrator is the author, but in this case, I think that’s what the author wanted.) In a novel, this approach comes across as defensive. If this were a memoir or even a poem, it wouldn’t be an issue.

I’m all for pushing the novel form in new directions, and I have no business preaching on the dogma of literary form. I just know that I had the same reaction as I did when I read Lincoln in the Bardo: it wasn’t a novel, but it was brilliant for whatever it was, and I would absolutely recommend it to others.