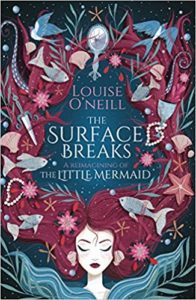

The Surface Breaks: A Reimagining of The Little Mermaid is a wonderful feminist take on the popular fairy tale. Louise O’Neill stays very close to Hans Christian Anderson’s original classic story (as opposed to the Disney version), but gives her little mermaid (Gaia/Muirgen) a much darker back story and provides a fuller description of the world that exists under the sea. Little mermaid Gaia has grown up under a misogynistic patriarchal system, where women are valued for their beauty alone. Gaia and her five sisters are daughters of the brutish Sea King and the lovely mermaid Muireann, who disappeared on Gaia’s first birthday after being captured by humans. Or so the story goes. Gaia is now about to turn 15, the age at which a mermaid is allowed to break the surface of the ocean for one day to observe the world above. Gaia’s much anticipated trip to the surface will not only open a new world to her but will unleash questions and desires that she will not be able to bottle up again. The repercussions for Gaia and for the kingdom of mer-people will be enormous.

The Surface Breaks: A Reimagining of The Little Mermaid is a wonderful feminist take on the popular fairy tale. Louise O’Neill stays very close to Hans Christian Anderson’s original classic story (as opposed to the Disney version), but gives her little mermaid (Gaia/Muirgen) a much darker back story and provides a fuller description of the world that exists under the sea. Little mermaid Gaia has grown up under a misogynistic patriarchal system, where women are valued for their beauty alone. Gaia and her five sisters are daughters of the brutish Sea King and the lovely mermaid Muireann, who disappeared on Gaia’s first birthday after being captured by humans. Or so the story goes. Gaia is now about to turn 15, the age at which a mermaid is allowed to break the surface of the ocean for one day to observe the world above. Gaia’s much anticipated trip to the surface will not only open a new world to her but will unleash questions and desires that she will not be able to bottle up again. The repercussions for Gaia and for the kingdom of mer-people will be enormous.

O’Neill introduces the reader to Gaia/Muirgen on her 15th birthday. We learn that while everyone calls her Muirgen, her mother Muireann named her daughter Gaia. It is forbidden, however, to utter the name Gaia or Muireann. Gaia prefers the name Gaia and longs to know more about her mother, whom she resembles — red-haired, blue-eyed and beautiful beyond compare. Gaia also has the most beautiful singing voice in the kingdom, a talent that makes her all the more desirable and valuable to her father. His daughters’ beauty, talent and obedience serves as a reflection of his own power and greatness, and so any transgressions — in word, deed, or appearance — are ruthlessly punished. The Sea King, at public appearances, lines up his daughters according to their beauty, with the most beautiful (Gaia) given the place of honor next to him. Despite her youth, Gaia is already betrothed to Zale, a man as old as her father, and as power hungry. In a very Trump-like way, the Sea King commends Zale on his betrothal to his youngest, saying,

If Muirgen were not my daughter, perhaps I would have chosen her for myself.

Gaia, who fears and is repulsed by both men, dismisses this as “merman talk.”

Gaia’s prospects for the future are grim. In addition to being stuck in a betrothal to a man she detests, her once good relations with her sisters are unraveling. Gaia’s older sisters must worry about becoming “old maids,” single and without purpose in this kingdom. Sister Nia is also engaged and seems unhappy but will not reveal matters of her heart. Sister Cosima, once Gaia’s best friend, is jealous and resentful of Gaia for taking her place as favorite daughter. Grandmother Thalassa, Muireann’s mother, offers some consolation, but even she caves in to the patriarchal system. Gaia has no choice but to marry Zale, and Thalassa will not speak of her daughter, presumed dead after being captured by humans above. Yet, something seems amiss. If Muireann was “captured,” why does her father speak of her abandonment of them? Why did he not try to save her if he really saw what happened to her? And why does he allow his daughters this one trip to the surface to see the much abhorred world of humans?

Gaia has spent years dreaming about seeing the world above, and she cannot wait to spend the day after her birthday on this adventure. She takes off early and alone, and true to the Little Mermaid fairy tale, she sees a handsome young man (Oliver) on a boat that is beset by a storm. Gaia has fallen in love upon first sight of him, but when she intervenes to save him, she transgresses a law of the sea and risks starting a war with the Sea Witch and her minions, the Salkas (Rusalkas).

The Sea Witch Ceto and the Salkas are one of the many things I love about this story. I love the way O’Neill uses the lore about Rusalkas (drowned girls who died tragically due to the treachery of men) and her incredible “witch” Ceto to draw up the lines between an entrenched, sexist patriarchy and the powerful women who don’t “look right” or act the way society wants them to. Gaia will cut a deal with Ceto to become human, but the price she will pay — her voice — will be dear. I don’t want to spoil this part of the story, because it is excellent. Gaia, who will be named Grace by Oliver, sees that in some ways, life on land is similar to life under the sea. Women who are smart and strong and powerful are often ignored and disrespected. Oliver’s mother is a good example of this. O’Neill’s message to young (and not so young) women is right on point: don’t let a messed up misogynistic society label you fat, ugly, a witch, unnatural, or useless. Your voice is your power. Don’t give it up. Use it! Love who you are and don’t concern yourself with ridiculous shallow standards that others have set up.

O’Neill’s resolution to this fairy tale is awesome and inspiring. It is definitely NOT a Disney ending! This little mermaid is a story of female solidarity and empowerment. The Surface Breaks is a Scholastic Children’s imprint and would be suitable for teens and older. I think it would also make a nice companion to Madeline Miller’s Circe.