Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah was one of my favorite reads last year, and her Purple Hibiscus will be right up there on this year’s list, too. I don’t know how it took so long for me to find her books (correction: yes, I do), but she has quickly become one of my favorite writers.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Americanah was one of my favorite reads last year, and her Purple Hibiscus will be right up there on this year’s list, too. I don’t know how it took so long for me to find her books (correction: yes, I do), but she has quickly become one of my favorite writers.

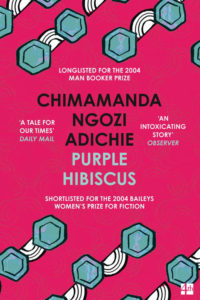

Purple Hibiscus tells the story of the Achike family through the eyes of Kambili, a young girl. Papa rules the family with an iron grip, infantilizing and militarizing and terrorizing his children in the name of love and religion. He’s a Big Man in Nigeria, a wealthy industrialist and publisher, one of the few willing to speak out against the latest military coup. He’s also generous with money, handing out small amounts in his tribal hometown and large amounts to the Catholic church and hospital. I was reminded of the moment early in Captain America: Civil War where Alfre Woodard’s character tells Tony Stark, “They say there’s a correlation between generosity and guilt.”

When events turn serious, Papa relents and lets Kambili and her older brother Jaja visit their aunt in a university town several miles away, where they get their first tastes of freedom. Kambili struggles with shyness and stammering out of fear of saying the wrong thing, made worse by her cousin of the same age criticizing her for her privilege and sheltered existence and inability to perform basic household tasks. Only now does Kambili start to express her own needs and desires and begin the process of growing into her own person.

The book’s structure means that we already know something has changed after this first visit to their aunt’s home, and we already know that the consequences will be severe. Adichie goes back to explain the lead-up to that visit and then follows onward after things start to fall apart, and she’s earned these later shocking moments with careful characterization and tight narrative. We know what these characters are capable of, so nothing comes across as gratuitous, only tragic.

This wasn’t an easy read. Several times, I had to close the book and walk away before I gave myself a rage stroke. Papa is fierce with his punishments yet also sincere in his own pain at having to inflict them. It’s probably the best embodiment of “this hurts me more than it hurts you” that I’ve ever seen, and while it’s completely believable, it’s also — obviously — infuriating. I grew up in a church that worshipped James Dobson’s Focus-on-the-Family methods of raising and disciplining children, and I’ve experienced some of what Kambili goes through in this story, and I’m still messed up for it, yet I know I’m lucky it wasn’t worse. People do terrible things in the name of their sincerely-held religious beliefs, and there isn’t enough time or money to make amends.