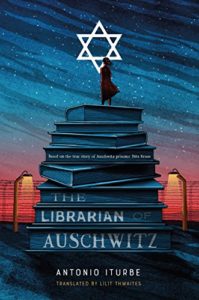

The Librarian of Auschwitz is a fictionalized account of real events that occurred in the Auschwitz-Birkenau labor camp, 1944-45. The main character Dita Adler is based on a real person named Dita Polachova Kraus who was 15 years old when she and her parents were rounded up with other Jews from Prague and sent to the Nazi camps. At Auschwitz-Birkenau, Dita worked in what was known as the “family compound” in Block 31. Prisoners here were given “special treatment”; children were allowed to survive and even had a sort of sanctioned youth group thanks to an inmate named Fredy Hirsch. While the group was only meant to have games and physical activities, Hirsch secretly set up a school with teachers and a library consisting of a few old books smuggled in. Keeping the school and the books hidden and secret was a matter of life and death, and teenaged Dita was the librarian who guarded those books with her life.

The Librarian of Auschwitz is a fictionalized account of real events that occurred in the Auschwitz-Birkenau labor camp, 1944-45. The main character Dita Adler is based on a real person named Dita Polachova Kraus who was 15 years old when she and her parents were rounded up with other Jews from Prague and sent to the Nazi camps. At Auschwitz-Birkenau, Dita worked in what was known as the “family compound” in Block 31. Prisoners here were given “special treatment”; children were allowed to survive and even had a sort of sanctioned youth group thanks to an inmate named Fredy Hirsch. While the group was only meant to have games and physical activities, Hirsch secretly set up a school with teachers and a library consisting of a few old books smuggled in. Keeping the school and the books hidden and secret was a matter of life and death, and teenaged Dita was the librarian who guarded those books with her life.

The existence of Block 31 and the “special treatment” of the families within it was a matter of curiosity and concern for others in Auschwitz. Everyone knew that the Nazis must ultimately have some evil plan for the prisoners there; transports brought thousands upon thousands of Jews to Auschwitz regularly and most people were sent to the gas chambers unless they were deemed able bodied enough to work to death first. Thus, from the Nazi perspective, children were useless. Why were some allowed to live? Did it have something to do with Dr. Mengele, the infamous and evil doctor who performed medical experiments on inmates? After attracting his attention during an inspection in which the secret books were nearly discovered, Dita lives in fear that Mengele has special designs for her. In her fear and anxiety about this, Dita turns to the one person she counts on and admires the most — Fredy Hirsch. Fredy was a real person about whom writer Antonio Iturbe is able to provide much useful background information. Hirsch was highly esteemed in the camp; the children adored him and he always seemed very brave to Dita. When others questioned why he would take such an awful risk, starting the secret school and keeping books, he says, “…the children are the best thing we have.” Fredy urges Dita when she is feeling low to never give up, and it seems to her that Fredy practices what he preaches. While Fredy is liked and respected by others in the camp, he also is very private. There are things about his past and even about his activities in the camp that make Dita question whether or not he is the person she has thought him to be. Even when the family compound is broken up and the prisoners are sorted into those who will die and those who will be shipped off to other labor camps, Dita will continue to pursue the truth about Fredy and who he really was. The Postscript to the novel provides some suggestion as to what the truth might be.

While the main action focuses on Dita and her life in Block 31, and on the atrocities that Jewish prisoners suffered in the camps, the reader also learns about life before the war through Dita’s daydreams and about the situation of other prisoners. Iturbe researched several of the people Dita knew in the camps and is able to provide fascinating information about these real people. For example, we learn about Rudi the registrar who made a daring escape from Auschwitz and about Viktor the SS guard who fell in love with a Jewish girl and devised a plan to get her and her mother out of the camp. In a section at the end of the story called “What Happened to …” Iturbe provides updates on several of these people and their fates after the war.

The books and their importance to Dita’s emotional and psychological survival of the camps is at the heart of this story. One might wonder, as many at Auschwitz wondered, why anyone would take such a risk to save a few books when their discovery would mean death, possibly a horrible one involving torture. Dita took great care of about 8 books, including an Atlas, a Russian dictionary, and a controversial novel about a foolish, hapless soldier. For Dita, books provided an escape and encouragement. Characters from the books of her childhood still comforted her in the worst times and gave examples for her to follow in life, even in Auschwitz.

…it didn’t matter how many hurdles all the Reichs in the world put in her way, she’d be able to jump over all of them by opening a book.

Even when Dita leaves Auschwitz for Bergen-Belsen, leaving the books behind, she is comforted by the thought of them and their power.

The books are still in the hidey-hole, stored underground and sleeping deeply until someone finds them by chance and opens them, thereby restoring them to life, just like the Prague legend of the Golem, who lies inert in a secret place waiting for someone to resuscitate him.

The final chapters of the book describe in horrifying detail what life was like for Dita and others at Bergen-Belsen as the war ended, as well as briefly touching on the process of trying to rebuild a life after war.

The Librarian of Auschwitz is a beautifully told story about a very brave young girl who, in the face of horror, cruelty and death, was able to hang on to hope and persevere thanks to her teachers and to her love of books and learning. The details about life in the camps are disturbing but true. It is categorized as “juvenile fiction” and would be appropriate for middle school and older.