I provided a bare-bonesed introduction to the basic plot of this story in my review of volume one. Vision was created by Ultron to be a robo-destroyer with no agency. Vision was curious, and didn’t want to be a destroyer, so he rebelled from his creator and fought for good alongside the Avengers. In this book, he has created a wife and children. They live outside of Washington, D.C., and they try to live as others do – going to school, going to work, meeting the neighbors. In volume one, in response to neighbors wondering what the Visions were doing living in the suburbs, he tries to explain that they aren’t trying to accomplish or achieve anything – they’re trying to do nothing – to be normal. Being normal is harder than it looks. That brings us in to volume two, the back-half of the story.

Someone I respect once wrote about faith, hope, doubt, and belief. As humans, we have this central question – Why do bad things happen? More specifically, Why does God let bad things happen to good people? I think we call that the question of theodicy. The writer didn’t have an answer. At least, he didn’t have one that made neat sense. What he did have was an idea – the idea that a system of faith doesn’t answer these kinds of questions. The system of faith gets you through the times when there aren’t answers to these kinds of questions.

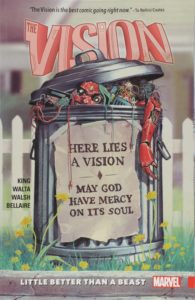

In some ways, Little Better Than a Beast reminded me of that theological essay. Not because volume two of The Vision is really about any kind of religious faith (although it is in there), but because it’s about faith itself. It’s about hope when hope doesn’t necessarily make any sense. Why bother being good? Is there any reason to be good? In the case of Vision and his family, they have an additional question to goodness: Why bother trying to be human? Another question, one we all must ask: What’s the point? A quote from the story:

I do not understand. Parents sacrifice their lives for their children. Then children become parents and sacrifice their own lives. And so all is sacrificed and nothing is gained. Life then becomes the pursuit of an unobtainable purpose by absurd means.

Does the book have a response to this observation? It does. I won’t give it away. It’s pretty good, though. I also saw that someone on Reddit make the observation that at least a draft of this story was called The Visions, which would’ve made more sense on its face, unless The Vision isn’t about Vision, or The Visions, but is instead about the dream. Or the hope.

Man, comics are deep these days.