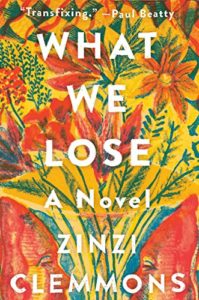

Our motto here at Cannonball Read is “Sticking it to cancer one book at a time,” and I think I have found a novel that epitomizes that sentiment. Zinzi Clemmons’ debut novel What We Lose is about losing your mother to cancer. Narrator Thandi was a college student when her mother died. Through Thandi’s recollections as an adult, the reader gets glimpses of how her family, her friends, her socio-economic background, and race intersect with her experience of her mother’s illness and death, and with her own deep grief. Clemmons writes of this grief from a personal place. Like Thandi, Clemmons lost her mother to cancer. And, like Thandi, Clemmons’ mother was from South Africa, a fact which allows Clemmons, through Thandi, to reflect on race and economic privilege as well.

Our motto here at Cannonball Read is “Sticking it to cancer one book at a time,” and I think I have found a novel that epitomizes that sentiment. Zinzi Clemmons’ debut novel What We Lose is about losing your mother to cancer. Narrator Thandi was a college student when her mother died. Through Thandi’s recollections as an adult, the reader gets glimpses of how her family, her friends, her socio-economic background, and race intersect with her experience of her mother’s illness and death, and with her own deep grief. Clemmons writes of this grief from a personal place. Like Thandi, Clemmons lost her mother to cancer. And, like Thandi, Clemmons’ mother was from South Africa, a fact which allows Clemmons, through Thandi, to reflect on race and economic privilege as well.

While the narrative is not linear, the novel is divided into 3 parts that follow Thandi’s progress through her mother’s illness and death, as well as her struggle to come to terms with it. In part one, Thandi introduces us to her mother and father. Her father is an African American math professor and administrator at a university. Her mother, a nurse, was an activist in South Africa before moving to the US. Thandi’s family visits their South African family on a regular basis, and Thandi notes that there is a difference in the way people of color in the US and South Africa view race. Her South African cousins think American blacks, as seen through movies and popular entertainment, are cool, but the cousins never refer to themselves as “black”. They are “coloured,” which indicates their mixed race heritage. Thandi is light skinned and in the US is often mistaken for Hispanic or Asian, but Thandi refers to herself as black. Her cousins find this awkward. In the US, Thandi’s family is pretty well off. They live in an affluent neighborhood and Thandi attends a school with mostly white kids. Her friend Aminah is also black and the daughter of an academic. Thandi recognizes that

…because of my light skin and foreign roots, I was never fully accepted by any race. Plus my family had money, and all the black kids in my town came from poorer areas.

Thandi is in an awkward position. On one hand, the white kids she hangs out with don’t consider her “a real black person,” and on the other hand, when she is accepted at a prestigious New England university, they call her an “affirmative action baby.” Thandi’s mother has some troubling ideas on race, as well. She is adamant that it’s not possible to have a true friendship with a woman whose skin is darker than your own and that straight hair is beautiful (and so Thandi must endure an unpleasant hair straightening process on a regular basis).

Race and class are unavoidable even when dealing with illness and death, and this is evident in part 2. The focus here is largely on Thandi’s mother’s cancer, the debilitating physical pain it entailed, and her death. Thandi writes that her mother received her treatments in an expensive neighborhood, and that most of the patients were black, many young and working class. This despite the fact that brochures and ads for treatment feature older, white individuals.

I never told my mother that, until then, I had thought of cancer as a disease of privilege. …AIDS was a disease of the people, I thought. Cancer, to me, was the opposite. Its cause was endorsed and healthily sponsored.

Despite treatment, though, Thandi’s mother did not recover; her illness progressed to the point that she was in constant pain, bedridden at home and eventually sent to hospice. Clemmons’ descriptions of the agonizing physical pain of cancer, of being helpless to do much of anything to help, and of her fear of losing her father in addition to her mother are brutally honest and deeply sad. In part two, Thandi reveals the depths of her own grief.

How would I ever heal from losing the one person who healed me?

In the early days, Thandi would sometimes dream about her mother, who would appear but fade out as Thandi tried to reach out to her.

I am most troubled when my mother is very present to me, when I dream of her extra vividly and can hear her voice.

Thandi eventually returns to school and takes a job related to AIDS research in New York. She struggles with the grief of losing her mother and with her dismay at her father when he finds a woman friend. On a business related trip, Thandi hooks up with Peter, and they attempt a long distance relationship, which becomes complicated by pregnancy. In Part three, Thandi details her own pain management in dealing with all of this. The marriage is troubled, and having a son/becoming a mother brings a new, startling perspective:

I have also felt sublime terror since he was born. It is impossible to think of him without thinking of his death.

I have never wanted someone as much as him and simultaneously been so afraid of that person being taken away.

Thanks to her family and her friends, Thandi is able to work toward her own healing and wholeness, but she notes that the void left by her mother’s death will never disappear. She says,

I’ve amazed myself with how well I’ve learned to live around her absence.

What We Lose is a beautifully written novel about that primal loss, the one that I think we fear the most even as adults — the loss of one’s mother. The writing is direct and heartfelt, and Clemmons provides some pertinent factual information (with footnotes) about cancer, race, and South Africa as well. It is a short novel, but has a powerful impact on the reader.