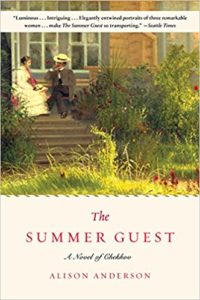

As much as I wish I could enjoy Russian classics, I tend to get bogged down in the political and philosophical discussions that go on and on and on and on. Most of the characters come across as self-important and obstinate and everyone just sits around arguing and insulting one another. I know this is an oversimplification but I just don’t get the appeal. “The Summer Guest”, a contemporary novel and only Russian adjacent, only reinforced that for me.

As much as I wish I could enjoy Russian classics, I tend to get bogged down in the political and philosophical discussions that go on and on and on and on. Most of the characters come across as self-important and obstinate and everyone just sits around arguing and insulting one another. I know this is an oversimplification but I just don’t get the appeal. “The Summer Guest”, a contemporary novel and only Russian adjacent, only reinforced that for me.

Three stories are interwoven here: A husband and wife struggling to hang on to their publishing company, the woman that they hire to translate the diary of a late 19th century Russian woman, and the story within the diary itself.

Beginning in 1888, Chekov’s family rents a guest house for several summers on the grounds of Zinaida Lintvaryova’s family estate in the Ukrainian countryside. Zinaida, a young doctor who is recently blinded by a growing tumor, forms a friendship with Chekov, who is also a physician. A budding writer of short stories and plays, Chekov confides in Zinaida that he has an idea for a novel. As he begins to write the novel in secret, he entrusts her with the manuscript which she keeps hidden for him under the floor boards in her room next to the diary in which she faithfully records the events of those summers. There is a lot of discussion of what both families and village folk get up to over the summer: fishing, side trips to other towns, impromptu musical concerts, picnics etc. but the haunting image is of Zinaida. She is an ambitious, educated woman quickly losing her independence to illness. She becomes everyone’s confessor; a safe person to confide in when needed, but she is often left alone as they frolic about the countryside. Her blindness imposes solitude.

The two storylines in present day also offer two strong female characters who suffer with their own solitude. Blindsided by the age of electronic publishing, Katya and her husband struggle with the inevitable end of their publishing business in London. He retreats to the office and drinks. She wanders around their home rehashing the past and wondering about the forks in the road that she did not take. In France, Ana, a literary translator, lives a quiet life in a quiet village after her divorce. Her Paris friends and city life have faded into the background and she has become a creature of routine and isolation.

Zinaida’s diary provides a way out of the isolation for each of them. Where is this novel that Chekov was writing? Is it complete? If they could find this novel, translate and publish it then a business and marriage could be saved; efforts and talent recognized and rewarded. It would be a new lease on life.

The author, Alison Anderson, is also a translator and I found that the most interesting parts of the story were the discussions about translation. Particularly, the process of translating someone’s words and the difficulty of translating Russian into English.

“Was that something the translator could infuse into a text? They weren’t supposed to, but then perhaps it was the language. Just the tortured poetry of Russian names seemed to bleed onto the page for the English reader.”

In some way, this novel is about just that. How do you translate someone else’s words and thoughts? How do you get inside of their head so that you can really understand intent? What is the key to unlock meaning?

Maybe the translation of Russian classics, the awkwardness of the character’s names and nicknames is what makes them so stilted to me. I’m a big fan of entering a world and staying in it. I can handle darker material and uncomfortable situations and I welcome robust prose. What I don’t enjoy is being yanked out of the narrative by awkward sentences or a monotony that causes me to drift off thinking about my grocery list as I read a particularly plodding passage. It’s not a terrible book. Just not my cup of tea.