I n my developmental English classes, my students and I often read Sherman Alexie’s literacy narrative, “Superman and Me,” where he describes learning to read at age three, puzzling out the meaning of text by looking at the frames of a comic book. He traces his impulse to read to his father—a man who filled the family house with books of all kinds—often purchased used and sometimes by the pound. He writes, “My father loved books and because I loved my father with an aching devotion, I decided to love books too.” In this short piece, there is only a brief mention of other members of the Alexie family and his father looms large.

n my developmental English classes, my students and I often read Sherman Alexie’s literacy narrative, “Superman and Me,” where he describes learning to read at age three, puzzling out the meaning of text by looking at the frames of a comic book. He traces his impulse to read to his father—a man who filled the family house with books of all kinds—often purchased used and sometimes by the pound. He writes, “My father loved books and because I loved my father with an aching devotion, I decided to love books too.” In this short piece, there is only a brief mention of other members of the Alexie family and his father looms large.

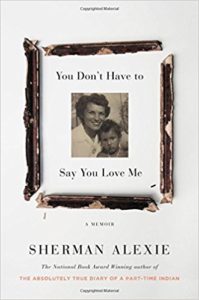

However, it’s clear after reading this jagged and raw memoir, that his mother, Lillian, loomed even larger. Constructed in a series of memory pieces and poems, Alexie tackles his complex and tortured relationship with his mother from every possible angle. On the one hand, he credits her for saving his life—by making the decision to stop drinking and for allowing him to leave the reservation as a teen to attend a mostly-white school in Reardon, Washington. However, he circles around and around the fact that she gave love and affection to many people in her community but did not give it to him.

As he tells stories from his past and present, Alexie grapples with the larger relationship he has to his community and family, to the history of oppression that tinges everything about reservation life, and to his own propensity of lying to tell the truth—that he suggests comes directly from his mother. There are so many things that stand out in this memoir—from a description of him having his Indian street cred questioned in a writer’s workshop and the response he wanted to give to his realization and meditation on the fact that the same white kids who voted him class president in high school most likely voted for Trump and all the complexity that entails. I had to stop and take deep breathes between some of the pieces because their impact was a sucker punch to the gut. Though I read this over the course of a few days, it’s the kind of book you want to come back to. The kind of book where you stop and say to your sister, “Can I read you this?” and you both end up with tears in your eyes and rocks in your throat.

I can’t even imagine how it feels to go on a book tour and read these pieces of heart and gut and barely scabbed over wounds night after night. I am not surprised that Sherman Alexie decided to take a break from his book tour—to grieve, to work through the complex issues that writing this book raised for him, and most importantly to simply rest. This book may be both a curse and a tribute to his mother but it is a testament to Alexie’s bravery and strength as a writer and a human being.

I’ll leave you with one of the poems that really grabbed me (and it was hard to pick only one):

Tyrannosaurus Rez

Yes, I’ve survived

All of the genocidal shit that killed

So many in my tribe,

And it is absurd

That I’ve made a great career

Out of nouns and verbs,

But, look,

It’s a miracle when any writer

Sells even on damm book.

So listen to me: I was conceived

With twenty thousand years

Of my ancestors’ stories

Locked in my gray matter

And flooding my marrow

So don’t think I’m flattered

With your homily

About how I must be

Some kind of anomaly.

I am my mother’s son.

I am my father’s child.

And they left me a trust fund

Of words, words, and words

That exist in me

Like dinosaurs live in birds.