Just a few days after I finished reading The Genius of Birds I observed four adorable white-crowned sparrows in my yard. Every fall I look forward to their arrival, when their journey from parts north ends in my Southern California backyard. Each year they arrive in mid to late September–seemingly bringing more friends each time–and spend the winter and early spring enjoying the Los Angeles weather, until a day comes in late spring when I realize I haven’t seen them in awhile. Next season, the pattern repeats. Do the same birds really visit every year? How do they remember where to go? Do they spread the word to others of their species? The wonder of migration is just one of the fascinating topics Jennifer Ackerman explores in The Genius of Birds, a delightful read for both bird enthusiasts and lay people alike.

Until the late 1990s, the idea that you could apply any description of intelligence to birds was ludicrous. For the gross misunderstanding of how birds’ brains are structured, we can thank 19th century German neurobiologist Ludwig Edinger. Considered the father of comparative anatomy, Edinger believed that evolution was linear: brains became more complex over time by adding new parts over old parts. The old parts, belonging to “lower” animals such as reptiles and birds, obviously could not compete with the complex structure of mammal brains. Only in the late 20th century did biologists start to understand that bird brains are structured completely differently than mammals. Birds have been evolving separately from mammals for over 300 million years, so while they may not have the neocortex that we mammals so proudly boast, they have their own cortex-like neural system for elaborate behavior.

The question isn’t so much “Are birds smart” as it is “How are birds smart?” Ackerman dives into different arenas where birds excel with gusto. She describes the feats of New Caledonian crows like Betty, who flabbergasted researchers by creating a hook from a piece of wire in order to retrieve food. Betty had seen and used hooks but had never fashioned one on her own nor even seen anyone fashion one before. (Seriously, check out that video, it will blow your mind.) She describes the language of birds like the chickadee, whose charming dee-dee-dees not only give the birds their name and make them easy for birders to locate, but are also considered by scientists to be one of the most sophisticated and complex communication systems of any land animal (the chickadee-dee-dee song signals a predator, with the number of “dees” indicating the predator’s size and, thus, level of threat). Ackerman examines the ability of many species of birds to mimic and to create beautiful, seductive songs to attract females. One might think that being able to sing a pretty song would be enough to win over a beautiful lady bird; it seems, however, that singing males are really demonstrating their intelligence–a superior songbird is not only better at singing pretty ditties, he’s probably also better at other tasks that require intelligence, like finding food for his mate and her brood.

A parrot’s ability to categorize objects by shape, color, and material; the English house sparrow’s ability to thrive outside of its native environment; a bower bird’s incredible artistic sensibility; even your every day pigeon’s ability to solve the Monty Hall Dilemma better than most people all demonstrate that there’s much more going on inside a bird’s head than you ever imagined. I could go on, but then I would spoil the fun of reading this book for you.

And this book is fun. Ackerman’s prose is accessible to non-scientists while never talking down to the reader. In one segment about a bower bird who fails to win over his potential mate, she talks about displays needing to be attractive, but not so aggressive as to drive away the female. “Courtship calls for more sensitivity than swagger,” she writes, “more tango, less kickboxing.” Passages like this, comparing a bird’s courtship display to a sexy tango, make me smile.

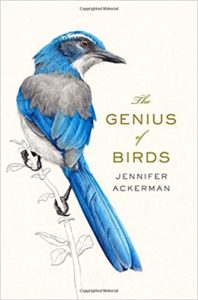

I’d be remiss if I didn’t mention the lovely artwork in this book. The cover boasts a gorgeous illustration of a scrub jay by artist Eunike Nugroho, and illustrations by John Burgoyne grace the beginning of each chapter, making this a must-own-in-print volume for me.

And yes, using a variety of techniques from mental mapping to olfactory clues to celestial navigation, those white-crowned sparrows really do remember where I live.