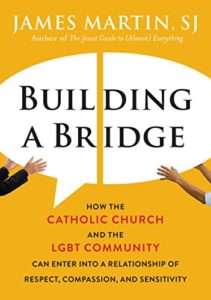

I’m kicking off banned book week with a book that has gotten a lot of attention, both positive and negative, in Catholic circles. Is it a banned book? If it isn’t yet it probably will be. The author has been banned from several Catholic speaking engagements because of it.

I’m kicking off banned book week with a book that has gotten a lot of attention, both positive and negative, in Catholic circles. Is it a banned book? If it isn’t yet it probably will be. The author has been banned from several Catholic speaking engagements because of it.

But he has also received support from prominent bishops and wouldn’t have been able to publish without support from his order, the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). This book, considered incendiary by alt-right Catholics, is not really radical, or I should say, it is as radical as true Christianity is. It advocates common sense, common decency, and basic Christian behavior. Sadly, in this day and age, that’s considered fringe thinking by some.

Father James Martin, Jesuit priest and writer, was inspired to write this essay in the wake of the 2016 Pulse nightclub shootings in Orlando. Pulse was a known gay club and its patrons were targeted because they were gay. In the wake of this horrible act of hatred, Fr. Martin was saddened to see so few Catholic bishops speak out in solidarity with our gay brothers and sisters. He notes only a handful of US bishops acknowledged the LGBT community in addressing this tragedy. Not long after the shootings, Fr. Martin was given the Bridge Building Award by an organization called New Ways Ministry. New Ways ministers to and advocates for LGBT Catholics. Fr. Martin was recognized for his many years of service on behalf of this community, and at the awards ceremony, he gave a speech called “Building a Bridge,” which became the springboard for writing this book. Fr. Martin’s goal is to provide a starting point for healing the division that exists between the institutional church and LGBT Catholics. He writes

…though this book invites both groups … to approach each other with respect, compassion, and sensitivity, the onus for this process is on the institutional church.

Why is the onus on the institutional church? Because it is the church which has made LGBT Catholics feel marginalized and not vice versa. Nonetheless, Fr. Martin believes that without concerted effort from both sides, things don’t get better.

Respect, compassion, and sensitivity are the essential components to healing the rift between the institutional church and LGBT Catholics, and Fr. Martin provides his thoughts on how both groups must exercise those virtues vis a vis one another in order for healing to occur. He begins by addressing the institutional church. It must respect LGBT Catholics first by acknowledging their existence. LGBT Catholics are a part of our church and deserve the benefit of outreach ministries. Another way to respect LGBT Catholics would be to call them by the name they prefer. Rather than “those afflicted with same sex attraction,” for example, why not call them gay or lesbian or whatever term they say is proper. Finally, the institutional church shows respect for LGBT Catholics by acknowledging the gifts they bring to the church.

The church, as a whole, is invited to meditate on how LGBT Catholics build up the church with their presence, in the same way that elderly people, teenagers, women, people with disabilities, various ethnic groups, or any other groups build up a parish or diocese.

Among the gifts LGBT Catholics have to offer are compassion toward the marginalized since they have been there, too; perseverance because of their faith; and forgiveness.

Fr. Martin spends some time dealing with the issue of LGBT Catholics who have been fired from their institutional church jobs because of their sexuality, and I imagine his thoughts on this topic enrage conservative Catholic readers. He argues that if following church teaching is a litmus test for employment, then the church needs to be consistent: no Protestants can work in the church because they don’t submit to Papal authority; no divorced and remarried Catholics if they didn’t get an annulment; and how about checking on employees’ commitment to helping the poor, offering forgiveness, etc.? Focusing on the LGBT issue while excluding others is discriminatory.

On the matter of compassion, first and foremost the institutional church must listen to LGBT Catholics and their families, and then it must stand with them in the face of persecution and discrimination. Fr. Martin writes that in the US,

Catholic leaders regularly publish statements — as they should — defending the unborn, refugees and migrants, the poor, the homeless, the aged.

This is one way to stand with people: by putting yourself out there, even taking heat for them.

But where are statements specifically in support of our LGBT brothers and sisters?

He goes on to point out that the LGBT community suffers from a high suicide rate and are the victims of more hate crimes proportionally than any other minority. When the institutional church fails to speak out on behalf of our LGBT brothers and sisters, it is a “failure of compassion.”

Finally, on the matter of sensitivity, Fr. Martin argues that in order to know the feelings of the Catholic LGBT community, members of the institutional church must know the community itself, know individual members of this community, become friends with them. It is the pastoral duty of the church to walk with the people — all of them. Fr. Martin then addresses objections to this expression of sensitivity. To those who believe that it is not possible to meet with LGBT Catholics in this way because of their sin, that it is imperative when meeting them to first and foremost admonish them to sin no longer, Martin gives a decided “Nope” in response. And to back up his position, he turns to Jesus of the Gospels. Jesus, if you pay any attention, spends a lot of time with marginalized people and outsiders whom many Jews might not have given the time of day. By way of example, Fr. Martin brings up the Roman centurion who asked Jesus to heal his servant and whose faith in Jesus bowled Jesus over. Jesus never yells at the centurion for being a pagan, nor does he deny the centurion his help. He commends his faith and heals his servant. So the institutional church should recognize the faith of LGBT Catholics and treat them as you would treat any other member of the faith community, who are all sinners, by the way.

Fr. Martin next turns to the Catholic LGBT community and offers his suggestions for how they might deal with the institutional church with respect, compassion, and sensitivity. While acknowledging the hurt, pain, and discrimination that many LGBT Catholics have endured, he reminds them that as Christians, we are all supposed to respond in a Christian manner, i.e., with love. Righteous anger has a place, but should be motivated by love and expressed respectfully. He asks LGBT Catholics to demonstrate compassion by trying to understand all of the jobs and responsibilities that fall on church leaders, and by striving to see the bishops in their humanity. He writes that an open LGBT community is relatively “new” to some of these guys and that giving them time and trying to reach out to them would be compassionate. He also writes of how it must be difficult for some of these churchmen, who might be gay themselves but could never admit this in the church, to come to terms with changes in attitude toward the LGBT community. Regarding sensitivity, Martin suggests that LGBT Catholics consider the different levels of authority within the church (your local pastor is not on the same level as the pope); that they be skeptical of mainstream media coverage of church matters; and again, that righteous anger be tempered by Christian love.

After addressing the two sides of the bridge, Fr. Martin then provides some scripture passages for reflection and possibly discussion. These are passages that in his ministry to LGBT Catholics have had particular resonance with them and with their families. Fr. Martin provides eight brief passages along with questions for contemplation, and a prayer for when you feel rejected.

Building a Bridge is a courageous step toward making our modern Catholic Church more catholic, i.e., universal, inclusive of all people. While it saddens me that some prominent Catholic institutions are put off by this book to the point where they won’t even allow Fr. Martin to speak about it, it does not surprise me. I know Catholics who would probably support that decision. I’m sure Fr. Martin’s advice would be to respond in love, which I will try to do. It occurs to me that Catholics who exclude and discriminate against LGBT Catholics are in need of a conversion themselves.